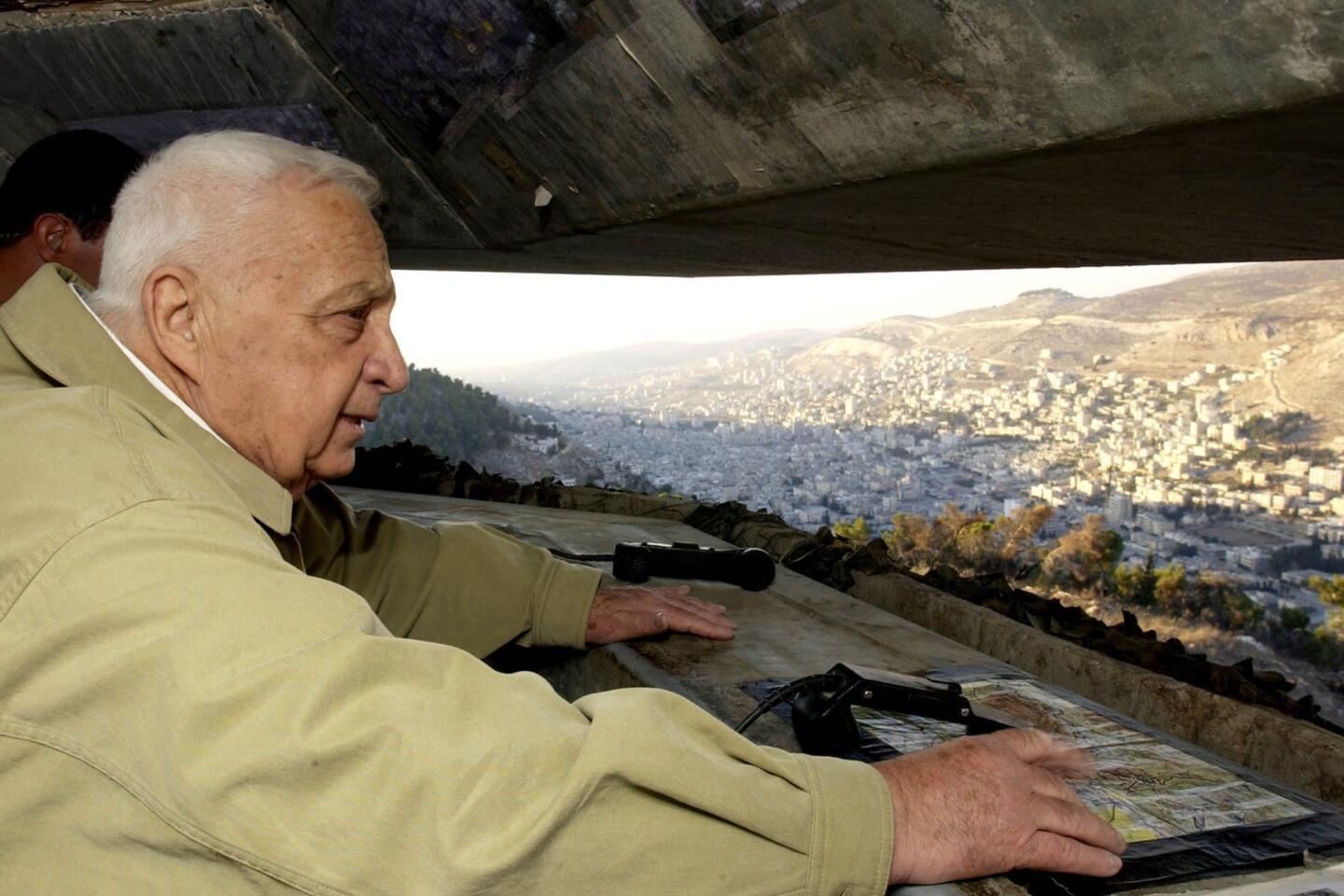

Ariel Sharon dies at 85; Israel’s controversial, iron-willed former leader

JERUSALEM — Former Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon, the iron-willed army general who fought in nearly all of his nation’s major wars and spearheaded Jewish settlement of Palestinian territories, then years later presided over Israel’s withdrawal from the Gaza Strip, died Saturday. He was 85.

The controversial leader, who had been incapacitated since suffering a severe stroke in 2006, was moved in 2010 to his ranch in the Negev desert at the request of his family. In September he underwent abdominal surgery, but his condition worsened this month as his organs deteriorated.

Sharon’s death at a hospital near Tel Aviv was announced by his son Gilad.

“That’s it. He’s gone. He went when he decided to go,” his son said.

Sharon, often called “the Bulldozer” for his aggressive style, endured many ups and downs in his lengthy career, but at the end was lauded as one of Israel’s greatest leaders.

“[Sharon] was a brave soldier and a daring leader who loved his nation and his nation loved him,” Israeli President Shimon Peres said in a statement. “He was one of Israel’s great protectors and most important architects, who knew no fear and certainly never feared vision. He knew how to take difficult decisions and implement them.”

Yet in the eyes of many Palestinians and even some Israelis, his actions were tantamount to war crimes; he was blamed for the massacres by Israel’s Lebanese allies of hundreds of Palestinian civilians in southern Lebanon in 1982 and previous attacks in Jordan.

Sharon devoted decades to the dream of establishing a “greater Israel” by seeking to populate the West Bank and Gaza with tens of thousands of Jews and exhorting them to seize the hills. But in his eighth decade, the old warrior set about dismantling some of the settlements. He withdrew settlers from Gaza and four small West Bank settlements in 2005 and declared his belief that Israel’s best chance for lasting security lay in drawing defensible borders and ultimately living side by side with a Palestinian state.

The shift infuriated Sharon’s right-wing supporters and led him to abandon the hawkish Likud Party for a newly formed centrist party, Kadima. Just months later, Sharon suffered the stroke, leaving much of his agenda unfulfilled. Analysts still debate whether Sharon was intending to make peace with the Palestinians or unilaterally consolidate Israel’s hold on the West Bank.

Most agree that the Gaza withdrawal did not turn out as Sharon had hoped. Weeks after he was stricken, the Islamist group Hamas won Palestinian elections, and it later seized control of the Gaza Strip, breaking with the rival Fatah party.

Two years later, prompted by a resumption of Hamas rocket attacks, Israel launched a 22-day military offensive in Gaza, killing 1,200 Palestinians and drawing an international outcry. The Kadima-led government was replaced by Likud, led by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, in 2009.

Sharon, born Ariel Scheinerman to Russian immigrants on Feb. 27, 1928, lived his life in the bloody crucible of the Israeli-Arab struggle.

He grew up in Kfar Malal, a cooperative farm just north of Tel Aviv, where his father, a stern taskmaster, demanded that he work long hours in the fields. Samuel Scheinerman pushed his son to achieve academically and imbued him with Zionist principles built around the imperative of settling the land.

Sharon first tasted combat as a teenager in Israel’s underground pre-state militia, the Haganah, and its strike force, the Palmach. He dropped out of college to join the Alexandroni Brigade in Israel’s 1948 war for independence. He was wounded in the battle for Latrun, when Jewish forces fought to lift the Arab siege of Jerusalem, and would be injured twice more in Israel’s wars.

Over the decades, he returned again and again to the battlefield as his country grew from an embattled statelet to a regional military power.

Forces under his command crushed the Egyptian army in the 1967 Middle East War, a conflict that brought Israeli control to East Jerusalem, the West Bank, the Gaza Strip, the Golan Heights and the Sinai Peninsula (returned to Egypt in 1982). In that war, Sharon commanded Armored Reserve Division 138, leading it to the banks of the Suez Canal when fighting broke out in June, and playing a key role in the capture of Sinai from Egypt. As chief of the southern command in 1971, he defeated Palestinian militants in the Gaza Strip in a series of raids, arrests, assassinations and the bulldozing of homes.

He retired from the army in 1973 and opened his political career by spearheading the unification of three right-wing parties into Likud.

But in October 1973, Sharon came out of military retirement to fight in the Yom Kippur War as commander of another armored division. This time, he crossed the Suez Canal and surrounded the Egyptian 3rd Army in a strategic counterattack that helped bring victory in a conflict that Israel’s leaders initially had feared they were losing.

During his military career, Sharon clashed frequently with chiefs of staff and other officers as he sought to transform the Israeli army into a fast-moving, innovative fighting force that defended the nation by going on the offensive.

Although his record includes a long list of military honors, it also contains repeated condemnations from government officials and generals who found him too unpredictable and reckless to serve as chief of staff or hold other key posts. But he had an almost mesmerizing effect on the first generation of Israeli leaders, including Menachem Begin and David Ben-Gurion, the nation’s first prime minister, who suggested that Sharon, while still a young soldier, take his more Israeli name.

After the war, Sharon launched his political career in earnest. He was elected in late 1973 to the Knesset, or parliament, but resigned the following year, only to be appointed security advisor to Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, of the Labor Party, in 1975. When Begin led Likud to power in 1977, Sharon was appointed minister of agriculture and became a driving force behind the Jewish settlement movement.

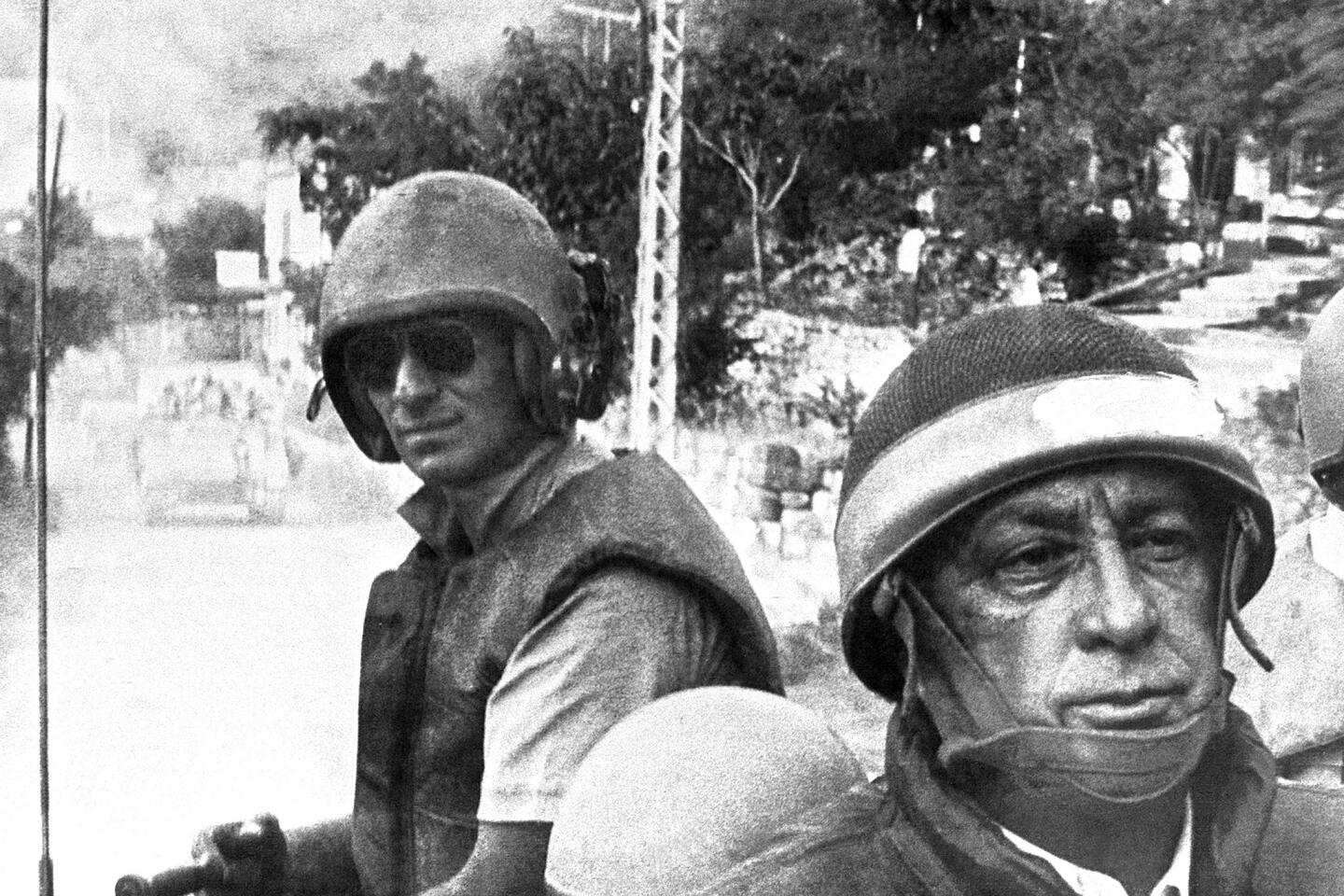

Begin was reelected in 1981 and he named Sharon his defense minister. Sharon’s military strategies had been studied by armies around the world, but then came his role as the architect of Israel’s costly 1982 invasion of Lebanon.

Sharon received Cabinet approval to thrust 25 miles into Lebanon for a strike that was supposed to last two days. Yasser Arafat’s Palestine Liberation Organization had established bases in southern Lebanon from which guerrillas were launching attacks on Israel. The ostensible goal of the Lebanon campaign was to clean out those bases.

Instead, the defense minister instructed the army to drive all the way to Beirut, where it laid siege to Arafat and his forces for two months. The invasion drove the PLO from Lebanon. But it also brought international condemnation of Israel for the high toll of civilian casualties and strained relations with its key ally, the United States.

Israel remained an occupying power in parts of Lebanon for 18 years. The war and occupation deeply divided Israeli society, shocked by the deaths over the years of 650 Israeli soldiers and thousands of Lebanese.

During that period, Sharon fell from power and rose again. The crisis for him came early in the invasion when Israel’s allies, the Lebanese Christian Phalangist militiamen, massacred at least 700 Palestinians in the Beirut refugee camps of Sabra and Shatila. In response, an estimated 100,000 Israelis gathered for a protest rally in Tel Aviv — at that point thought to be the largest such demonstration in the nation’s history — and demanded Sharon’s ouster.

Sharon later said he believed that during a visit to the United States in May 1982, he had received a “green light” from President Reagan’s secretary of State, Alexander M. Haig Jr., for his mission to remake the political landscape of Lebanon.

In court testimony several years later, Begin’s son Benny testified that Sharon had lied to his father about the scope of the invasion. It was a charge Sharon always denied. He insisted that the Cabinet knew and approved of his larger plan.

But his legacy would be forever tarnished by the massacres at Sabra and Shatila. The government-appointed Kahan Commission that investigated the killings found that Sharon was “personally responsible” because the deaths occurred while Israeli troops ringed the camps.

He was forced to resign in 1983 but came back a decade later. In 1993, after Rabin helped negotiate the Oslo peace accords, which recognized the PLO and led to Israel’s military pullout from most of Gaza and parts of the West Bank, Sharon became a leader of the deal’s right-wing opponents.

In 1998, Netanyahu, during his first stint as prime minister, appointed Sharon foreign minister, bringing him into talks with the Palestinians. Sharon helped negotiate an interim peace agreement in 1998 at the Wye Plantation in Maryland but refused to shake Arafat’s hand there.

In 2000, Sharon was widely blamed for helping spark a bloody conflict with the Palestinians, the second intifada, which followed the breakdown of U.S.-brokered peace talks at Camp David between Arafat and then-Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak.

Sharon, an opposition leader, insisted on “reasserting Israeli authority” by taking a high-profile tour on Sept. 28, 2000, of the Jerusalem holy site known to Jews as the Temple Mount and to Muslims as the Noble Sanctuary. Palestinian riots broke out and eventually mushroomed into an armed conflict, including many suicide attacks against Israelis, that over five years claimed more than 4,000 Israeli and Palestinian lives.

After the breakdown of the peace talks and the outbreak of the intifada, Barak abruptly resigned and called for new elections. Netanyahu expected Sharon to step aside and allow him to run as Likud’s candidate. Sharon refused.

His political comeback reached triumph in 2001 when he was elected prime minister, burying Barak in a contest that focused almost exclusively on the need to get tough. Supporters called him by his nickname, greeting him during campaign stops in the marketplaces of Tel Aviv and Jerusalem with cries of “Arik, king of Israel!”

With a relentless series of suicide bombings rocking Israeli cities, Sharon responded in the spring of 2002 with Israel’s most sweeping military offensive since the 1967 war, sending the army into all the major population centers of the West Bank. Hundreds of Palestinian militants were arrested or killed, but the campaign also cost the lives of many Palestinian civilians.

Within a few years, his onetime conservative allies were denouncing him as a traitor for uprooting 21 Jewish settlements in Gaza and the four smaller ones in the northern West Bank. Denunciations from the right grew into frequent death threats.

For most of his adult life, Sharon was unwavering in his belief that only military might and a pioneering spirit could ensure Israel’s survival in a hostile region.

To his enemies, he was “an Israeli Caesar,” a man whose dreams of remaking the Middle East dragged Israel into dangerous conflicts.

“In war, I’d follow him through fire and flood,” onetime Israeli President Ezer Weizman wrote after Sharon, as defense minister, led the invasion of Lebanon. But he said Sharon had lost the ability to distinguish between his personal goals and those of the state.

Palestinians and many other Arabs saw in Sharon all they hated and feared about Israel. To them, he was “responsible for all the disasters that befell the Palestinians,” in the words of Yasser Abed-Rabbo, former Palestinian Authority minister of information and culture.

Sharon’s personal enmity toward Arafat, president of the Palestinian Authority, reached new heights during the intifada. Sharon stopped short of assassinating his bitter foe but kept Arafat confined to his West Bank compound until just before the Palestinian leader’s death in Paris in late 2004.

In typical blunt fashion, Sharon said there was little reason to mourn Arafat’s passing. But he was criticized both within Israel and in Washington for failing to do more to reach out to Arafat’s moderate successor, Mahmoud Abbas.

Sharon’s personal life was marred by tragedy. His first wife, Margalit, a nurse, died in a car accident in 1962. A year later, he married her younger sister, Lily.

In 1967, Gur, Sharon’s only child by Margalit, died when a playmate accidentally shot the 11-year-old boy in the head with an antique rifle of Sharon’s. He bled to death in his father’s arms. Lily died of cancer in 2000.

Survivors include two sons, Omri and Gilad, and four grandchildren.

As prime minister, Sharon lived alone in the official residence in Jerusalem. But he escaped as often as possible to his sheep ranch.

He delighted in receiving world leaders and journalists there, and would conduct tours, lecturing on the history of Israel and the Jewish people — and the fine points of animal husbandry.

Former Times staff writer Mary Curtius and Jerusalem bureau news assistant Batsheva Sobelman contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.