When in Doubt, DISCLOSE

Terry Bening thought she and her husband, Steve, had bought their dream home: a $343,000, two-story Spanish-style house in Chino Hills with views of the twinkling lights of the Inland Empire below to Mt. Baldy above.

But in October 1997, when the Benings moved in, they discovered the house was slowly breaking apart. A crack running up a wall in the master bedroom was their first clue. Tracking the fissure down the wall, Terry lifted the bedroom’s carpeting and discovered a 3/4 inch-wide gap in the foundation running almost the entire length of the north side of the house.

“The previous owner had put a large armoire in the corner [where the crack was],” Terry said, “and a tall potted plant. They had hidden the problem.” As a result, she said, both the Benings and their home inspector had missed it. What the previous owners had not done during escrow, according to Terry, was disclose that about one-third of the house--built in 1989--had been constructed on unstable land and was slowly starting to sink and break apart.

Since 1985, California law requires home defects to be disclosed by sellers during escrow on a Transfer Disclosure Statement. The three-page form asks sellers to tell all about their home--everything from whether the oven is in good working condition to whether the home has had major damage from a fire, earthquake, flood or landslide.

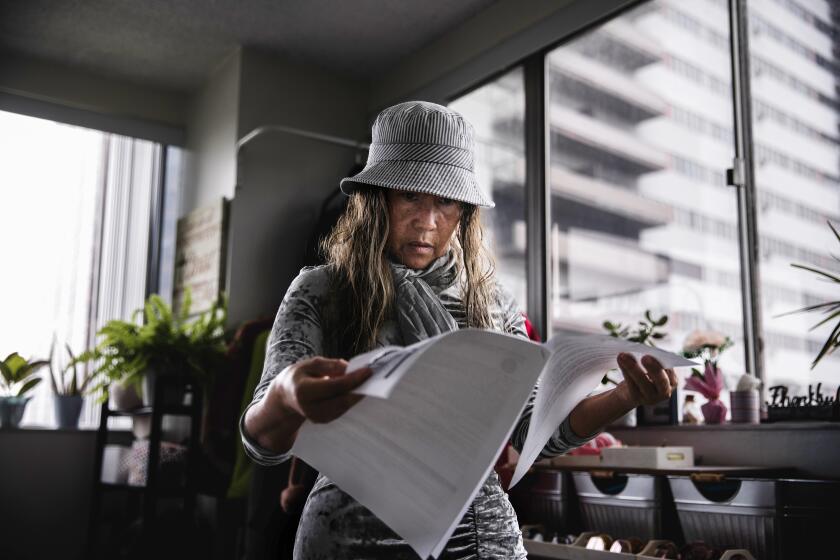

After consulting numerous engineers, the Benings, both 49, now know that their dream house is slowly sinking and shifting at a rate of 1/12 of an inch a year. “I’ve lost the feeling of home as a safe place,” said Terry, a college professor.

During a four-year legal battle that began in 1998, the Benings have recovered some costs from the listing agent and the home inspector. But the funds have barely covered their legal costs, they said.

The Benings are not able to receive compensation from the sellers, who knew of the problem, because they filed for bankruptcy. And the courts found the builder is free from obligation because the statute of limitations--in this case, three years after the first homeowner had discovered the problem--had run out.

*

“My husband and I will have to pay for this problem,” Terry said. “It’s a slow process, but eventually [the house] could collapse.”

Despite the threat of lawsuits, sellers sometimes conceal issues about their home they feel will break a deal. But often, sellers have lived in a home so long they don’t notice a leaking pipe or think to mention that water collects at the doorway in a driving rain.

Still, other sellers fear disclosing something like a death or murder in the home will stigmatize their house right out of the market.

Gary Effron, a Los Angeles-based attorney who specializes in real estate law, said a good way to eliminate guesswork about disclosure is to ask yourself: “If I were a buyer, is this something I would want to know?”

All sorts of issues and sticking points can arise during escrow as a result of the gray areas on disclosure--everything from how much water pressure there is in the shower to one San Fernando Valley seller who wanted to disclose that her house was haunted by her mother.

“I thought it was bizarre,” said real estate agent Jerry Berns, 59, who, along with all real estate agents, also have a responsibility to do a visual inspection of all accessible areas of a property and disclose anything they find. “But I did think about disclosing it. The acid test for disclosure is anything that could conceivably make a difference to a buyer.” (Ultimately, the presence of the purported ghost was not disclosed.)

To get all the facts, real estate agents usually sit down with a seller for at least an hour to go over the house’s history. During this meeting, sellers will check off items on the Transfer Disclosure Statement, or TDS, as it is known. If sellers have a big problem to disclose, they are encouraged to use additional pages for explanation.

*

“The only downside to this,” said James Joseph, owner of Century 21 Grisham-Joseph in Whittier, “is now we have a paper blizzard. Years ago we had far fewer forms to fill out.”

While the majority of problems arising from nondisclosure occur accidentally, some homeowners--such as the Benings--believe they were set up to buy flawed property.

Russell and Donna Merriweather bought their first home for $189,000 in September 1999 in the Leimert Park area of Los Angeles. According to Russell, a counselor who works with substance abusers and developmentally disabled adults, two days after moving in, he and Donna discovered the walls of the back corner of the master bedroom were eroded and rotted away due to water damage from a leaking roof. The walls had been cosmetically patched and painted, according to Russell, and furniture and boxes had prevented a complete visual inspection of the area when the couple walked through the property.

“When we opened up the wall,” said Russell, 51, “we were devastated.”

“I should have been more aggressive during escrow,” Russell said. “No one disclosed that there was water damage to the roof.” Both the agents representing the Merriweathers and the seller of the home said they were not aware of the damage either.

Regrettably, Russell waived his right to a home inspection, which could have caught the problem and potentially put a brake on escrow until the seller had either reduced the price of the home or had it repaired. But even inspectors can miss problems--as in the Bening case--or can’t get access to areas of the house because of an accumulation of furniture and junk.

*

Paul and Mary Gafner discovered a crack in the foundation of the garage of their Tustin home after escrow closed. An inspector missed the problem because of a mountain of boxes and toys stacked in the garage.

Not having access to certain areas should be referenced in the inspector’s report, according to Coldwell Banker real estate agent Janet Loveland. But, Loveland said, that shouldn’t be the end of it. “A buyer should ask that the stuff be removed so a second inspection can happen,” she said.

The Gafners--who were first-time home buyers--decided to live with the crack.

“We were naive,” said Mary, 42. “You just have to cover every square inch when you buy a house. You have to make the buyers move things around to see things.”

Sometimes, a homeowner learns of a problem with a property by happenstance. First-time home buyer Ken Sandberg paid $205,000 for a 1,400-square-foot ranch-style home in Simi Valley in February 1997. Three months later, Sandberg, who works in computer support for Walt Disney Feature Animation, found a note on his front door from the Ventura County Assessor’s office asking if the property’s earthquake damage from the 1994 Northridge earthquake had been repaired.

Shocked, because no such damage had been disclosed during escrow, Sandberg learned through extensive research that his home had withstood so much damage during the 6.7 temblor that the county had assessed the home’s structural value at nothing.

Since then, Sandberg has learned that during the earthquake, the garage separated from the house and the swimming pool was no longer level. Additionally, he discovered the house sustained a 6-foot-long crack about 3/4-inch wide under the kitchen floor, a 1-inch-wide crack running the width of the house in the home’s slab and damage to the home’s foundation.

According to Sandberg, the previous homeowner’s repair of the damage was improperly done. “If the wind would blow, the house would creak.”

Unlike most nondisclosure lawsuits, which end up settling out of court, Sandberg won a legal judgment against the sellers and the sellers’ real estate company to have his purchase of the property rescinded plus full repayment of attorney’s fees--about $20,000.

Sandberg would eventually have the house seized by the sheriff from the previous owners for nonpayment of his judgment. The house would then be sold two more times: at a sheriff’s auction and by another owner who placed the home in a trust, which like homes in probate and foreclosure, do not have to meet the same disclosure requirements.

Consequently, the couple who live in the house today knew nothing of its previous problems until, Sandberg said, he knocked on their door and told them.

“I’m one of the lucky ones,” Sandberg said. “I got out of this mess.... The people that own the house now are the victims.”

*

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX)

How to Question Disclosures

Advice for not getting tripped up on disclosure:

* Question any items of concern listed on the Transfer Disclosure Statement.

* Ask seller questions about the house or neighborhood not listed on the Transfer Disclosure Statement.

* Make sure your agent provides you with a current Transfer Disclosure Statement, which is updated frequently. (The most recent form is dated October 2001.)

* Make sure your inspector is a California Real Estate Inspection Assn. member and be present at the inspection.

* Request that necessary repairs be made by appropriately licensed professionals.

Source: Barbara Nichols, real estate broker and expert witness in real estate and general contracting

*

Allison B. Cohen is a Los Angeles freelance writer.