Jacaranda co-founders aiming high with classical music series

Thirteen months ago, on a calm, cool midnight in Santa Monica, Patrick Scott slipped out of the tiny Miles Memorial Playhouse and flopped on the stairs like a runner midway through a marathon.

A few hours earlier, the first of 32 piano soloists had launched into a 24-hour, nonstop rendition of Erik Satie’s “Vexations,” which requires repeating one page of mystical, proto-Minimalist music 840 times.

It was the kind of evening that Scott and his partner, Mark Alan Hilt, live for. As co-founders of Jacaranda, a decade-old classical music series based at Santa Monica’s First Presbyterian Church, the men believe that when it comes to serving the interests of idiosyncratic, exceptionally demanding music, more is always more.

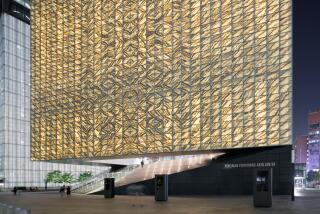

PHOTOS: Arts and culture in pictures by The Times

“That’s the thing about Jacaranda: The music always comes first, the composer’s intentions always come first,” Scott, 64, was saying. “So we thought, ‘We can’t skimp, it has to be the real deal, and do all 840 repetitions.’”

A few moments later, Hilt, 54, an organist who is Jacaranda’s and First Presbyterian’s musical director, joined Scott outside for a breather. “I am so loving this, I can’t tell you,” he said. Then he added, in a tone more exhilarated than anxious, “We’re running about 10 minutes behind.”

Artistically, Jacaranda is a product of combining certain opposites: contemporary with older music, a church setting with a secular audience, an informal vibe with rigorous programming choices.

In doing so, Jacaranda has challenged its audiences to elevate their tastes, and developed long-standing relationships with many dynamic young musicians such as pianist Gloria Cheng and cellist Timothy Loo, who appreciate getting the chance to stretch artistically. Meanwhile, its collaborations with the region’s other classical music entities, such as the Los Angeles Philharmonic and Los Angeles Opera, have been steadily increasing.

CHEAT SHEET: Fall arts preview 2013

“I would say nine times out of 10 they pick repertoire that is completely out of my scope,” says Loo, citing pieces such as Iannis Xenakis’ notoriously nettlesome “Nomos Alpha.” “And so I’m really always very excited to learn something new. I would never, ever say no to them.”

For Scott and Hilt, Jacaranda represents a harmonic convergence of dissimilar temperaments and skill sets. The couple met cute in 1994 at the now-defunct Tower Records on the Sunset Strip, where Hilt was working as a sales clerk, after their fingers briefly became entangled in Scott’s shopping bag.

Hilt, the son of Kansas farmers, grew up steeped in Methodist church music and first absorbed classical music by borrowing records from his small-town library. For years, he has juggled Jacaranda duties with his longtime job as music director of Harvard-Westlake college prep school. Although chatty and good-humored in person, he regards making music as “more an intellectual thing” than an emotional one.

“Most of the music I do with Jacaranda is so freaking hard, I can’t surrender to that,” he says. “I really have to think about where I am in the piece and where I’m going in the piece and what I want to happen on the way.”

Scott, who hails from a Manitoba mining town, is the softy. He gets choked up remembering how the late L.A Weekly music critic Alan Rich once singled out Hilt as L.A.’s brightest young opera conductor, or when mentioning some positive feedback he received from the Los Angeles Children’s Chorus after they performed at Jacaranda.

Before he began running the series full time, Scott led previous lives as, among other vocations, an L.A. after-school enrichment program administrator and a soap opera costume designer.

“I think if I ever write my autobiography,” he says, “it’s going to be called ‘Dilettante.’”

But by the late 1980s, as the AIDS crisis spread, Scott yearned for a new and meaningful enterprise. Hilt, for his part, wanted to push himself to new artistic frontiers, even though for many years he was struggling with renal failure that was relieved only when he received a kidney transplant in 2010.

“That kidney has taken over his life,” Scott says, laughing. “It’s his sister’s kidney, and she’s really butch. It’s like now he’s swimming every day, he’s running, he’s got weights in his office and a chin-up bar. It’s like, ‘Who are you, and what did you do with my boyfriend?’”

When Jacaranda launched in fall 2003, the metropolitan area had few regular outlets for edgy, technically formidable 20th century music, apart from the L.A. Phil’s Green Umbrella series and Zipper Concert Hall at the Colburn School.

West of the UCLA campus, the offerings were even sparser for aficionados of thorny iconoclasts like Xenakis, Janácek, Cage, Messiaen, Reich, Ligeti and Stockhausen. Equally rare were programmers who would put together a bill of works by, say, Charles Ives, Ben Johnston, Philip Glass and Erich Wolfgang Korngold, as Jacaranda is doing this March.

Richard Valitutto, a pianist with the L.A. modern music collective Wild Up, who’s making his Jacaranda debut in May with Mozart’s Serenade for Winds (“Gran Partita”), says that Jacaranda’s daring programming is a boon to the city’s emerging artists and to its adventurous young audiences.

“It’s a modern, 20th and 21st century music series, but they’re not afraid to program Liszt, for example,” he says. “If it supports the artistic view of the concept of a particular program, or it provides interesting context to the other music, then they see that as a priority. And that’s a beautiful thing.”

In particular, it was Scott and Hilt’s unabashed idolatry for Olivier Messiaen, the French avant-garde composer of lush, erotically charged, monumentally daunting works, that spawned Jacaranda.

In 2002, they held a one-off, three-concert festival in honor of Messiaen’s death. The positive responses included praise from Times music critic Mark Swed, who noted approvingly that the overdue tribute had been organized “not by a music professional but by an enthusiast, Patrick Scott,” and that an early organ piece of Messiaen’s had been “strongly played” by Hilt.

Soon after, Hilt, who was working as First Presbyterian’s organist, was offered the chance to replace the church’s departing music director and to program its upcoming Friends of Music season. He and Scott decided to expand the Friends of Music series at the church and move it from Sunday afternoons to Saturday nights.

“Mark came home,” Scott recalls, “and I said, ‘Listen, the acoustics in this place are beautiful,they’ve got a really nice Steinway B, they’ve got this organ, they’ve got restaurants all around, they’ve got parking across the street, and there’s nothing going on on the Westside at all, zip, zero, zilch.’”

Hilt hardly needed persuading. Few churches, he says, “have the luxury of being very adventurous,” with rare exceptions such as Philip Brunelle’s VocalEssence in Minneapolis.

For its 10th anniversary season, which continues with a Nov. 9 program of music by Adler, Reich, Schoenberg and Zeisl, Jacaranda will face some of its customary challenges. Seating capacity at First Presbyterian is limited to 425, or 565 if you bring in chairs. So is the annual budget (around $350,000), and the subscription base (about 100).

“We’re proselytizing ourselves every which way to try and make it work,” Scott says. “I’m really itching to get full houses, but it’s hard because we just like classy music. What can I tell you?”

----

Jacaranda: Music at the Edge

When: 8 p.m. Nov. 9

Where: First Presbyterian Church, Santa Monica

Tickets: $20 to $45

Info: (213) 483-0216 or https://www.jacarandamusic.org

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.