Ayelet Waldman, ‘Bad Mother’

At the moment, Ayelet Waldman’s biggest fear is mountain lions. Specifically, having her throat ripped out by one. She’s also afraid of sharks and, dare she say it, her husband, Michael Chabon, dying of cancer. While we sit talking in the writing studio in the couple’s backyard, an earthquake (maybe around 4.0) rattles the floorboards and the windowpanes. Waldman is explaining how she got into the mommy business. She’s talking pretty fast, like the Jersey girl, Wesleyan smarty-pants, Harvard Law School, former public defender, mother of four she is and doesn’t even notice the earthquake. I repeat: doesn’t even notice the earthquake -- thinks it’s her neighbor’s vacuum cleaner.

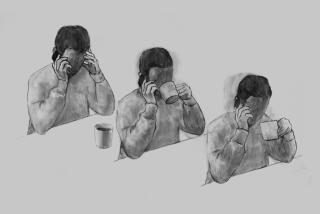

Why is this important? Because motherhood is all about fear -- warding it off, facing it, explaining it away, dealing with it in the middle of the night (yours, theirs, everyone’s). “Bad Mother,” her latest book, is about facing your fears, your mistakes, your shortcomings, openly and honestly -- in that wonderful way that describing a nightmare can make it dissolve.

The last decade of mommy books has been categorically appalling for the level of blame: work vs. stay at home; breast vs. bottle; organic vs. toxic, etc. The tone of most mommy literature is shrill. Why? Because the stress level is high and getting higher. There’s less time, less money and more danger. As for the dream that one day our government will recognize the importance of motherhood and create that dreamy Scandinavian society complete with decent maternity leave, decent healthcare, child care, more money for education, well, maybe not in this lifetime. “Bad Mother” is Waldman’s effort to face reality. “This book,” she spells it out up front, “is about the perils and joys of trying to be a decent mother in a world intent on making you feel like a bad one.”

Berkeley is resplendent. Flowers everywhere, cafes, dogs, bookstores. Waldman and Chabon and their four children, Sophie (14), Zeke (12), Rosie (8) and Abraham (6), live in a gorgeous Craftsman house. Waldman rushes in from belly dancing class, offers the homemade cornmeal cranberry muffins that her children refuse to eat and some chocolate-covered sunflower seeds that go down surprisingly well. Sitting around her kitchen table, surrounded by her children’s drawings and books and all that sunlight, you’d swear this was the Bay Area version of the Cleaver household.

But in “Bad Mother,” Waldman admits to a head-spinning number of shortcomings. She tried juggling lawyering and motherhood (“I even accepted collect calls from my clients in lockup while pumping”) but left her job when Sophie was still a baby. She was jealous of Chabon, a stay-at-home writer who got to “spend his days with her, and I was jealous of my daughter, who spent her days with him.”

After a week at home, she began to lose her mind. She started writing -- first, the “Mommy-Track” series of mystery novels; and two others: “Daughter’s Keeper” and “Love and Other Impossible Pursuits.” A veteran blogger, she wrote articles on mothering for various online and print publications. But when an essay she wrote for a collection called “Because I Said So: 33 Mothers Write About Children, Sex, Men, Aging, Faith, Race and Themselves” was reprinted by the New York Times in 2005 under the title “Truly, Madly, Guiltily,” the mommy police came out in force. In the essay, Waldman admitted that she could survive the loss of a child but not the loss of her husband; that, yes, she loved her husband more than her children.

UrbanBaby and other sites hung her out to dry. Waldman was stopped by sanctimonious Berkeley mothers, mothers all over the country, and was called to defend herself on “Oprah.” Here’s what you do, she counsels, about mothers who criticize your parenting in public, like the Santa Monica yoga mom who wagged her finger at me for turning a corner too fast: “Go passive-aggressive. I would stop the car in the middle of the intersection, get out and say, ‘I am so sorry. So very, very sorry. I am a bad mother.’ ”

This is sort of what Waldman has done in “Bad Mother” (though there’s an enormous amount of wisdom and thoughtfulness in the book). With her children’s permission, she has written about her fears for each of them. That Sophie, who prefers the “sexy witch” costumes at Halloween to the toaster or chocolate-chip cookie get-ups, will make the same mistakes Waldman did -- sleeping around at a young age and losing her virginity to a thoughtless Israeli soldier. Her fears that Zeke’s ADHD will limit his choices in life. (Waldman also admits to her disappointment upon hearing about Zeke’s learning disability). She has written about her suspicion that Zeke may be gay (not exactly an issue in Berkeley). She worries about Rosie’s “decoding problem.” Waldman writes about her own depression, being diagnosed as bipolar, about taking antidepressants and learning that she was pregnant with her youngest child, Abe. Abe was born with a palate that made breast-feeding difficult, and he almost starved before anyone noticed he wasn’t getting sufficient nutrition.

But perhaps the most affecting chapter in the book is about the baby, nicknamed Rocketship, whom the couple aborted after amniocentesis revealed genetic abnormalities. Waldman writes boldly and honestly about their decision: “Aborting my baby is the most serious of the many maternal crimes I tally in my head when I am at my lowest, when the Bad Mother label seems to fit best,” she writes. “Rocketship was my baby. And I killed him.”

“When we choose to have an abortion,” she writes, “we must do so understanding the full ramifications of what we are doing. Anything less feels to me to be hypocritical, a selfish abnegation of reality and responsibility.” And, she says: “I don’t think of myself as the Nazi who says kill all the mentally retarded people.”

What would she do if Sophie became pregnant? “If Sophie said she was keeping the baby, well, then I’d freak out.” Waldman is living proof that we are in the age of no clear role models. “We are the transitional generation -- raised to think we could do anything.” Waldman, 44, writes about the pressures her own mother, a liberal intellectual who stayed in a bad marriage for 45 years, put on her to put career first.

“I wish she’d had a different life,” she says of her mother. In our lifetime, she says, the pressure to work ridiculous hours has increased. “Even in professions, like publishing, where it’s completely unnecessary to stay until midnight! . . . Women have to sacrifice ambition to have children.”

There’s so much invested when you have children, she says, that the pressure to get it right is all the more intense: “These people for whom we have sacrificed better be worth it.” Waldman laughs about the stay-at-home moms who have channeled their ambition into their children’s nursery school -- the Brownie troop leader she knows who used to work as a pediatrician -- “those Brownies didn’t just get a CPR badge; they know how to perform tracheotomies!”

“Look,” she says, “if you ask a child, ‘Would you rather have a fulfilled mother or a stay-at-home Sylvia Plath, they’ll pick Sylvia Plath every time. But I think it’s really important that children don’t feel their parents’ emotional lives depend on their success.”

Waldman feels extremely lucky that she and Chabon agree on so much about parenting and that they are able to share the work. He writes at night, and Waldman writes while the kids are in school (she has just finished a novel called “Red Hook Road,” which she has been working on for 3 1/2 years). Waldman has written in this book and elsewhere that she and her husband are one of the few married couples she knows who still have a sex life, a good sex life. “I was a lesbian for a semester at Wesleyan -- it was a graduation requirement,” she jokes. “That’s how bored I was before I met Michael.”

While we are talking, Chabon comes in with Sophie, Zeke and Abe. They have been shopping for vintage clothing on Telegraph Avenue and are eager to show us their haul, including a dress that fits Rosie perfectly.

We leave the bustling kitchen to talk in the studio out back. Waldman admits that she regrets the chapter on Zeke’s ADHD and plans to give her kids a bit of a break from public scrutiny. She says being bipolar isn’t all bad -- in her book she notes that some great writing has been done by very depressed people. While she needs to take extra care of herself (“eternal vigilance is the price you pay for bipolar disorder”), her hypomania has meant that in one year she was able to write three books.

Waldman is deluged with responses to her various books and columns and blog entries. She feels that the Internet has become “a toxic place” and that women are “more prone to ad hominem attacks than men.” She claims to have committed every bad review she’s ever gotten to memory, to still be guilty of wanting to be liked. “I did not have any friends in seventh grade,” she says. “I was a geek -- not the good kind.” She hopes that her daughters will not feel so crummy about themselves.

The point is that Waldman is happy. She likes the extensive community of writers in the Bay Area, she’s happy and hopeful about Obama’s America, and she likes writing. She can pick her kids up from school and spend the rest of the day with them. (“The whole point of writing is you don’t have to bathe!”) The couple is pretty well known in the Bay Area and are often stopped on the street and at local functions -- “the kids hate it that we are recognized,” she says. “That was the great thing about L.A. -- no one recognized the writers!” The biggest problem in Berkeley, Waldman says, is “that we can’t be mean to our kids in the grocery store.”

Salter Reynolds is a Times staff writer.

Bad MotherA Chronicle of Maternal Crimes, Minor Calamities, and Occasional Moments of GraceAyelet WaldmanBroadway Books: 208 pp., $24.95

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.