Challenging the whiteness of American architecture, in the 1960s and today

“This book tells the story of how I got a free Ivy League education.”

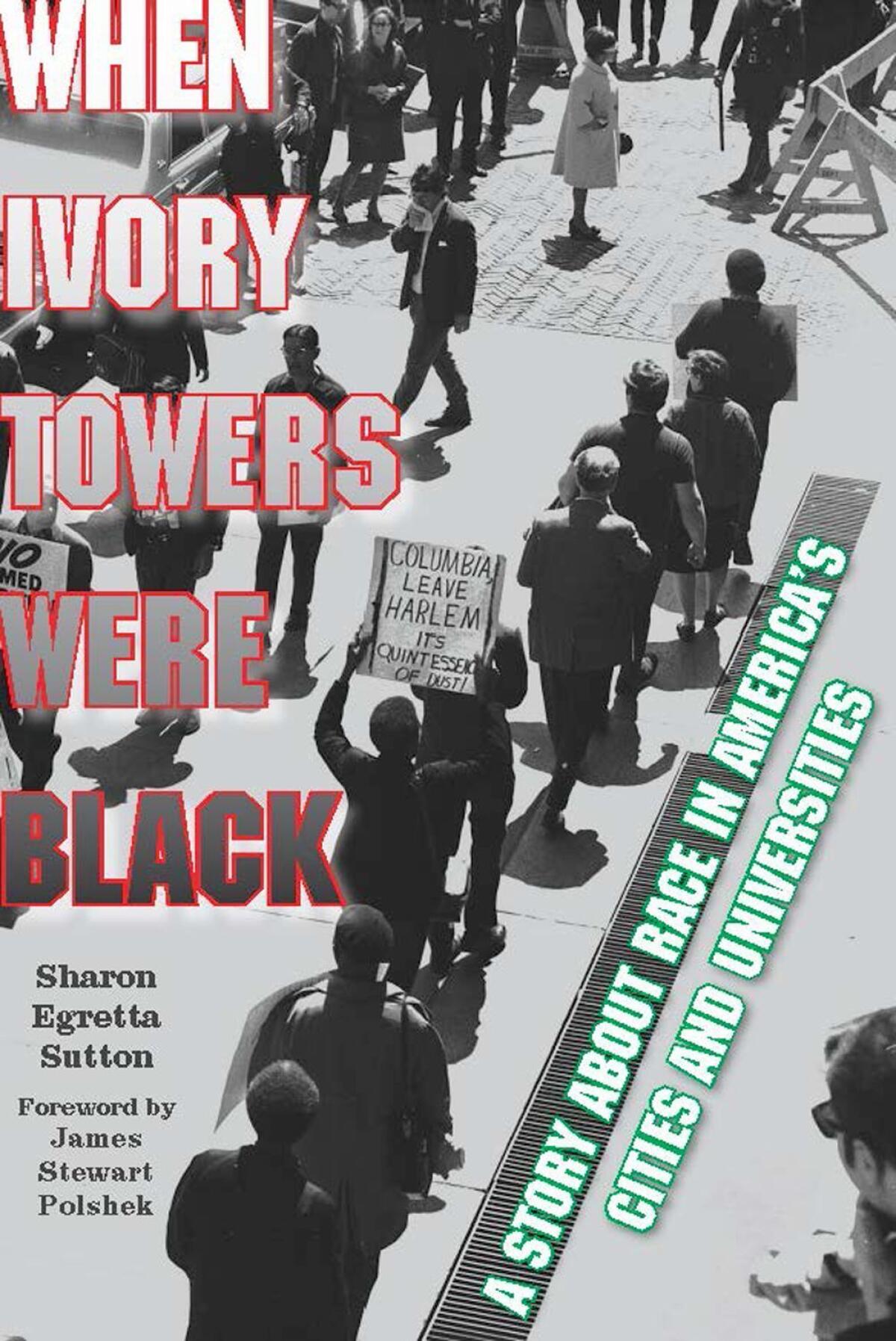

That's the arresting opening sentence of Sharon Egretta Sutton’s “When Ivory Towers Were Black,” an unusual hybrid of memoir, institutional history and broadside against the entrenched whiteness of the architecture profession in this country.

The institution in question is Columbia University and, in particular, its department of architecture and planning. The time frame is between 1965 and 1976, “mirroring the emergence and denouement of the black power movement,” as Sutton notes. And the narrative is really a two-part story, exploring how an era of intense student protest at Columbia, which peaked in the spring of 1968, gave way to a remarkably successful if short-lived effort to recruit students of color to study architecture and urban planning on the university’s campus in Morningside Heights, on the southwestern edge of Harlem.

I could paraphrase the story of how Sutton, who is now professor emerita at the University of Washington and a fellow of the American Institute of Architects, became one of those students, but I am unlikely to improve on her version. And the details, in any case, are what make it memorable. It takes place in the dog days of summer, 1968.

“At the time,” she writes, “I was working as a musician in the orchestra of the original cast of the Broadway musical Man of La Mancha, playing ‘The Impossible Dream (The Quest)’ on my French horn over and over, eight times a week. As an antidote to that mind-numbing sameness, I had begun taking interior design classes at Parsons School of Design during the day (since I mostly worked at night). But in August … I received a call from the secretary for Romaldo Giurgola, a famous architect who was then chairman of the Division of Architecture. One of my teachers at Parsons had worked in Giurgola’s architecture office and had told him about this black woman who was in his class. And that’s how I was recruited to the School of Architecture.”

(This is probably a good spot to point out that 1968 was also the year that the civil rights leader and National Urban League Executive Director Whitney Young delivered a fiery keynote speech at the AIA convention, telling the architects gathered there that they shared “the responsibility for the mess we are in in terms of the white noose around the central city” and that a black Yale architecture student he knew “did want you to begin to speak out as a profession, he did want in his own classroom to see more Negroes, he wanted to see more Negro teachers.”)

What Sutton didn’t learn until far later was that she and the rest of the newly recruited students were brought to Columbia by a pair of related forces. The first was a $10-million Ford Foundation grant to the university in 1966 to be used for “urban and minority affairs.” The second was the student uprisings that peaked in 1968, when Avery Hall, which held the architecture school, was occupied by protesters along with four other buildings on the Columbia campus.

In the wake of those protests, which ended with a violent police raid that Sutton says unfolded over “two terrifying hours,” administrators discovered a) a pressing need to diversify the architecture department and b) that the Ford Foundation money had never been spent. And so the outreach to French horn players taking classes at Parsons — and others like Sutton all over the country — began in earnest.

Together the new students changed the demographics of the Columbia architecture school dramatically and in very short order. Between 1968 and 1971, the percentage of students of color in the department jumped eight-fold, to 16% from 2%. In the planning division, which Sutton credits for pursuing reforms even more actively, the percentage was higher.

At first, Sutton writes, the experience was exhilarating for her and the other recruited students. They entered a department that had been turned upside down during several years of unrest, opening the eyes of white students and faculty to the sort of injustice and police aggression that the black students had dealt with their entire lives.

This, for Sutton, seemed to produce a kind of equilibrium in the department, or at least revealed some common goals. The recruits, she writes, “shared with the Avery insurgents a commitment to change a racist society and the Eurocentric education offered at Columbia.”

Things weren’t perfect. Many of the recruits felt isolated. But student demands, on the whole, were taken seriously. There was grant money for traveling. African American architects on the faculty, including the late Max Bond, served as mentors. The recruits more than held their own academically. Inside Avery, Sutton writes, “the period between 1968 and 1971 was a magical, intoxicating time.”

Then it all fell apart — or, to be more precise, drained away. A backlash against affirmative action and Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society programs during the Nixon administration; a financial crisis in New York and at Columbia; the departure of key figures from (and uncertainty over accreditation within) the architecture department: All of it contributed to an atmosphere where recruiting students of color received less attention and even less funding by 1972.

A new dean — James Stewart Polshek, who contributes the book’s foreword — took over. The number of students of color graduating from the department peaked in 1973, the year Sutton earned her degree, dropped by half the following year and continued to decline steadily after that. Students, Sutton writes, “sought out the tranquility of an earlier era.” The experiment was over.

Sutton’s book, which began as an oral history of the recruits and their experiences at Columbia and elsewhere, includes updates near the end on what her former classmates are doing now.

But it is perhaps most valuable as an instruction manual for a new effort to diversify the field. As Sutton notes, today just 1.5% of all registered architects in the U.S. are African American. In more than 40 years of teaching architecture, Sutton recently told Columbia’s Mabel O. Wilson, “I maybe have had 12 black students. So I have this huge sense of how special that situation was when I was a student at Columbia.”

The strategy — how and where Columbia spent the Ford Foundation money — is laid out in detail. How much went to grassroots efforts to identify promising students and how much to top-down ones. How much was spent in the New York area versus nationally. The great success the recruiters found by making repeated visits to six historically black colleges and universities.

If we can only show the resolve to follow it, the road map is there.

christopher.hawthorne@latimes.com

Twitter: @HawthorneLAT

ALSO

Just in time for opening day, a new book on the (complicated) history of Dodger Stadium

Doug Aitken's 'Mirage': a funhouse mirror for the age of social media

How much is a landmark worth? A visit to Herzog & de Meuron's controversial Hamburg concert hall

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.