Anatomy of an art conservator’s laboratory

This month, Christina O’Connell begins conservation on the Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens’ iconic “The Blue Boy,” Thomas Gainsborough’s 18th century masterpiece. The yearlong effort is part of the exhibition “Project Blue Boy,” which O’Connell co-organized with curator Melinda McCurdy.

During the exhibition, O’Connell will work between a temporary conservation lab set up in the museum’s Thornton Portrait Gallery, as the public watches, as well as in her private laboratory. Her permanent workspace feels partly like a high school chemistry lab, filled with multiple microscopes, and partly like a professional framer’s studio, with spacious work surfaces and standing studio lights.

Here’s O’Connell’s take on her six “go to” tools of the trade and why they’re important to conservation science.

'Blue Boy' revisited: The Huntington is saving its 18th-century masterpiece — and you get to watch »

The Hi-R NEO 900 Haag-Streit surgical microscope: “It all starts with looking and observing, so the microscope is a key tool, being able to zoom in and look at the surface carefully. I’ll use this one every day in the first phase of the ‘Blue Boy’ treatment. It’s an ophthalmological microscope, on loan from the company itself, which typically lends things to hospitals for surgery.”

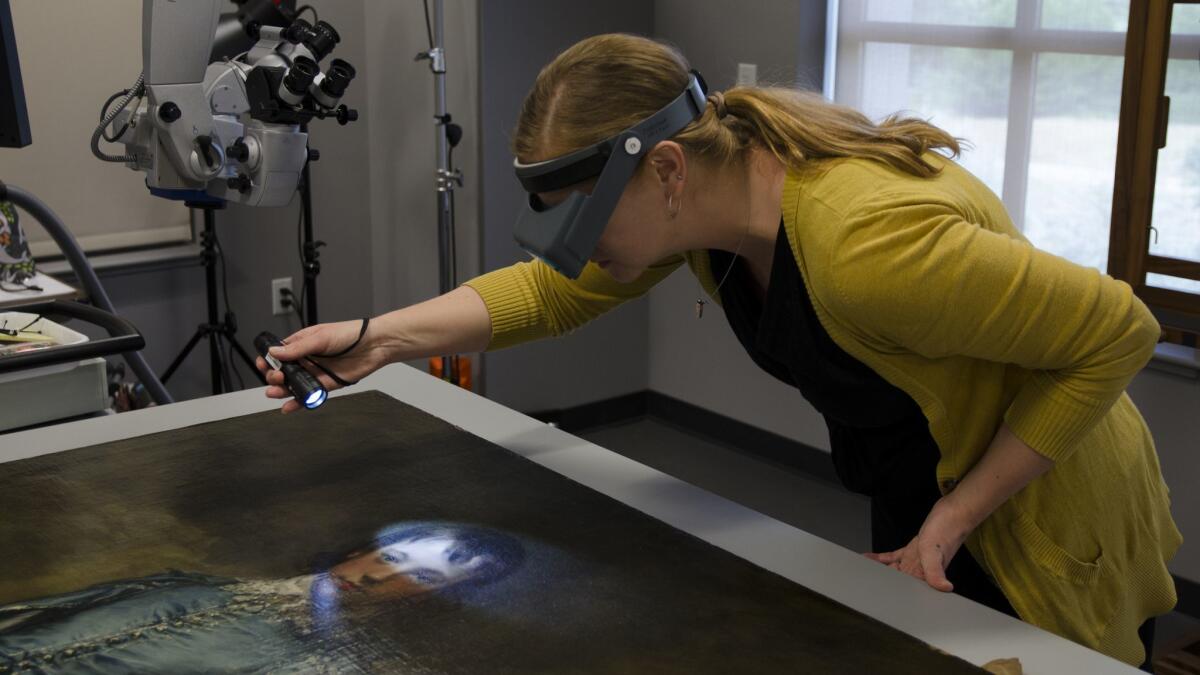

The Optivisor: “This one’s really important, because sometimes you don’t want to zoom in too far, you want to step back a little. This helps you get that perspective. Jewelers and watchmakers also use it — it’s easily worn and magnifies a little bit, but your hands are free to do your work. They’re pretty affordable, you can buy them on Amazon. You get into a zone when you’re really looking carefully, you’re very focused. In the second ‘Ghostbusters’ movie, Sigourney Weaver is a conservator and is wearing one.”

A good easel: “Sometimes I work on the painting flat because gravity needs to be your friend with flaking paint; but other times, I need to be able to read the painting, whole, in the orientation it needs to be viewed in, spacial depth and composition, so it’s upright on the easel. This one is custom-designed by a woodworker and cabinet maker in Maine who’s been making easels for decades.”

Ample lighting: “This sounds very simple, but good lighting. That’s [partly] why some of the treatment, in the end, will finish in the [private] lab, because I need good, optimized lighting — just being able to see everything clearly when I’m removing varnish, color matching accurately when doing in-painting. The spectrum from red to violet, northern light has that full spectrum of all those wavelengths of light, whereas lamps and artificial lighting might be cooler or warmer but not as even a distribution of all those wavelengths. That helps you see the full spectrum of colors in the artwork.”

Hand tools: “The brushes I use are essentially the same for painting as well as adhesive work — good, sable hair brushes with a really fine point. They’re different sizes — they range from really small to less small, but they’re all really small. A triple zero to a Size 1, where the brushstroke can be really tiny, where I can work in 1 to 2 millimeters at a time. I also use a tiny spatula, so if the paint’s missing or there’s a hole in the surface I use fill material — I mix it together with raw materials — and smooth it out with the spatula and shape it to match the original surface. That’s key. My in-painting will never be invisible if my fill’s not good.”

Paint and varnish: “I use new conservation materials like varnishes and paints that are both stable and reversible. It’s stable pigments bound in modern synthetic resins. We’ve identified at least four blues that Gainsborough used — ultramarine, azurite, smalt and Prussian blue. We’re using conservation colors that are essentially modern versions of his pigments. When you’re adding them, you want them to last a really long time and not change color, so they match the painting for a long time; but you want to be able to remove them later, if you need to. Anything I’m adding to the painting should not permanently alter it.”

Follow me on Twitter: @debvankin

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.