Anthony Newman ready to ‘wow’ on Disney Hall’s ‘Hurricane Mama’ organ

“From the beach to Bach.”

That’s how Los Angeles-born organist Anthony Newman describes his journey from a boyhood home at 1708 Washington Blvd. to his standing as one of the world’s foremost interpreters of Johann Sebastian Bach’s early 18th century music.

On Sunday, Newman returns to Walt Disney Concert Hall for a solo organ recital featuring a mix of baroque classics and some of his own compositions. (Tickets for the concert, which starts at 7:30 p.m., are $20.)

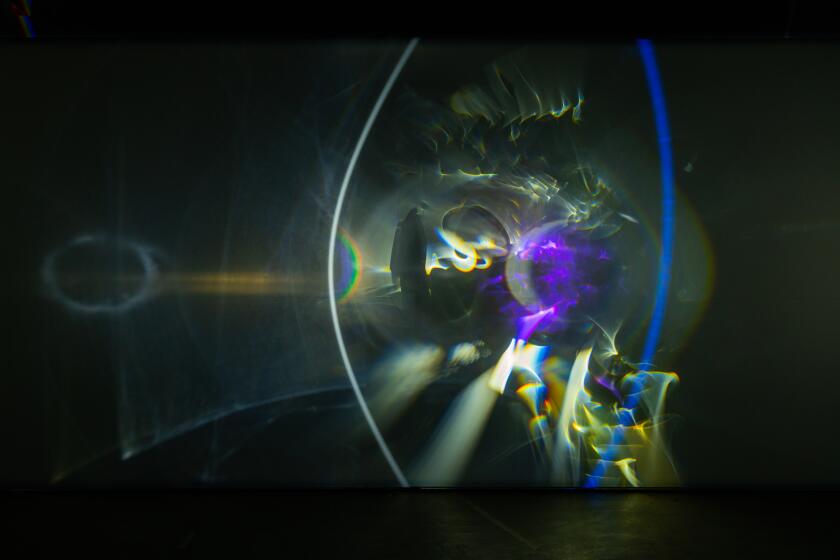

Playing Disney Hall’s 72-stop, 6,000-plus pipe organ — dubbed Hurricane Mama by composer Terry Riley — is something Newman, despite his years playing organs at famous venues like Carnegie Hall and Notre Dame Cathedral, looks forward to with great anticipation.

“The good thing about it is that the organ is very powerful and grand sounding, so if you play reasonably well, it’s going to be effective,” Newman says at a Manhattan rehearsal studio, “but the other thing is: Every ounce of energy falls on you. It’s a huge instrument. It has some inner excitement which is like filled with adrenaline.”

Newman, 73, is a man of calm temperament (a serious meditator for the last 40 years, he says). But he has long felt that Bach and baroque music requires excitement and adrenaline. In the late 1960s, this view — and a well-reviewed harpsichord concert at Carnegie Hall — caught the attention of Columbia Records executive Clive Davis.

“Clive thought I could be the young hippie Bach player,” Newman recalls. “Myself and André Watts were the chosen two keyboard players by Clive to be groovy. Now, from my standpoint, I’m a rather quiet person, I’m not at all groovy. But I do think that music should sound vital, no matter what it is. And that’s what Bach didn’t sound like in those days — not vital.”

It’s hard to imagine a time when a 27-year-old Harvard-educated harpsichordist could be considered controversial or part of the counterculture, but Newman says his eight years as a Columbia recording artist led to lots of notoriety: “I say notoriety because at this time, because this was before period performance practice. People just didn’t play Bach brilliantly, or as quickly, did not add ornamentation — and I was just the opposite, and I got in trouble for that.”

Newman’s playing did ruffle feathers. A New York Times review from 1976 complained, “his accents … startle, even outrage.… It is like listening to someone who speaks your native language with breathtaking fluency but in a thick accent, sprinkled with outrageous mispronunciations.”

But some of this controversy was no doubt Davis’ and Columbia’s plan to sell records. Perhaps more than Newman’s playing style, the album covers of the “hippie harpsichordist” may have been what put off some critics and classical musical listeners back then. One album was titled “Organ Orgy” and featured a cartoon of Wagner playing a pipe organ while wearing a Valkyrie helmet. A Goldberg Variations album from 1971 shows a Monty Python-like image of a fish devouring a bust of Bach with snakes coming out of the composer’s mouth.

As time passed, Newman became less a novelty; Davis left Columbia, and Newman found himself without a major label. Lucky for him, baroque music was undergoing a major shift. Thanks to a growing movement in London and Amsterdam of playing with period instruments, Newman’s more lively style was gaining acceptance.

“The curious thing is, it’s taken hundreds of years for Bach to become Bach,” he says. “The complete edition of his work only happened in 1850. That’s 100 years after Bach died. And then it became academically sophisticated music that you should study because it’s intriguing. That went on for 100 years — and it’s only in the last 30 years that’s it’s become ‘wow’ music.”

As a composer, Newman not only has seen changes in how music is played over the last half-century but also has strong views on evolving tastes in contemporary music. “I have a different point of view for new music. Which is that nontonal music is basically a tremendous mistake,” he says. “I lived through it all because I was Luciano Berio’s teaching assistant, I knew Stockhausen and Boulez and all those people … and I have many good friends who do write in this way, and I’m sorry if I offend them.” But, he says, after years of studying, he knows: “Audiences do not want to hear nontonal music.”

When pressed — does he really believe that so many 20th century composers were off-track? — Newman thinks for a moment, then answers candidly: “With great sincerity, I think they were off-track. And I don’t think it will survive. The only thing that can survive is there has to be some aspect of a melody that you remember and some aspect for that harmony that serves as the background, because that’s what music has always been, and the great works of art are just that.”

At Disney Hall, Newman will premiere two compositions for pipe organ. He insists that because they have clear, “friendly” melodies, audiences will like them.

As an author of new organ pieces, Newman may finally be at the right place at the right time. There are few young organ players making noise right now — most notably Cameron Carpenter, whom Times music critic Mark Swed called “an extraordinary virtuoso” a few months back. Carpenter just released a CD on Sony, which took over Newman’s Columbia label, and is being marketed as a rock star. The CD cover features the young Carpenter swooning over a keyboard while rocking a wife-beater and a Mohawk.

Newman is encouraged by Carpenter’s success — and that of other players like Stephen Tharp, Paul Jacobs and Mahan Esfahani. For Newman now, as then, it’s less about the marketing than the music.

“I like Carpenter’s playing,” he said. “It’s not historical playing, but why should it be?”

When asked whether he sees himself in this next generation of players, Newman thinks and then says: “You know, the last concert Carpenter did at Disney Hall, on the same organ I’ll be playing, someone wrote, ‘But he was wearing tennis shoes!’ And guess what: I used to wear tennis shoes when I was playing at 25.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.