Review: What to see in L.A. galleries: Hot-button greeting cards, mesmerizing photograms

Bill Clinton and George H.W. Bush were vying for the presidency in summer 1992 when Erika Rothenberg's satirical greeting cards were shown at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. You're bound to do a double-take at that date when you step into the Charlie James Gallery in L.A.’s Chinatown, where the MoMA exhibition "House of Cards" has been reprised.

The cover of the first card on the rack that wraps around the room shows hands of assorted colors pointing to the words "You're a Liar, a Manipulator, a Phoney and an Adulterer!" Inside, American flags flutter around the follow-up: "Maybe you should run for president!"

The relevance of these works today is good news and bad news, a testament to Rothenberg's astuteness. Rothenberg addresses aspects of sexual and racial discrimination, poverty, abuse, ignorance and intolerance that are specific to the moment of the works' creation — and turn out to be dismayingly timeless. None of the 80 or so searingly funny greeting cards requires historical context to be decoded 25 years later. Those same hot buttons remain as hot as ever.

SIGN UP for the free Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

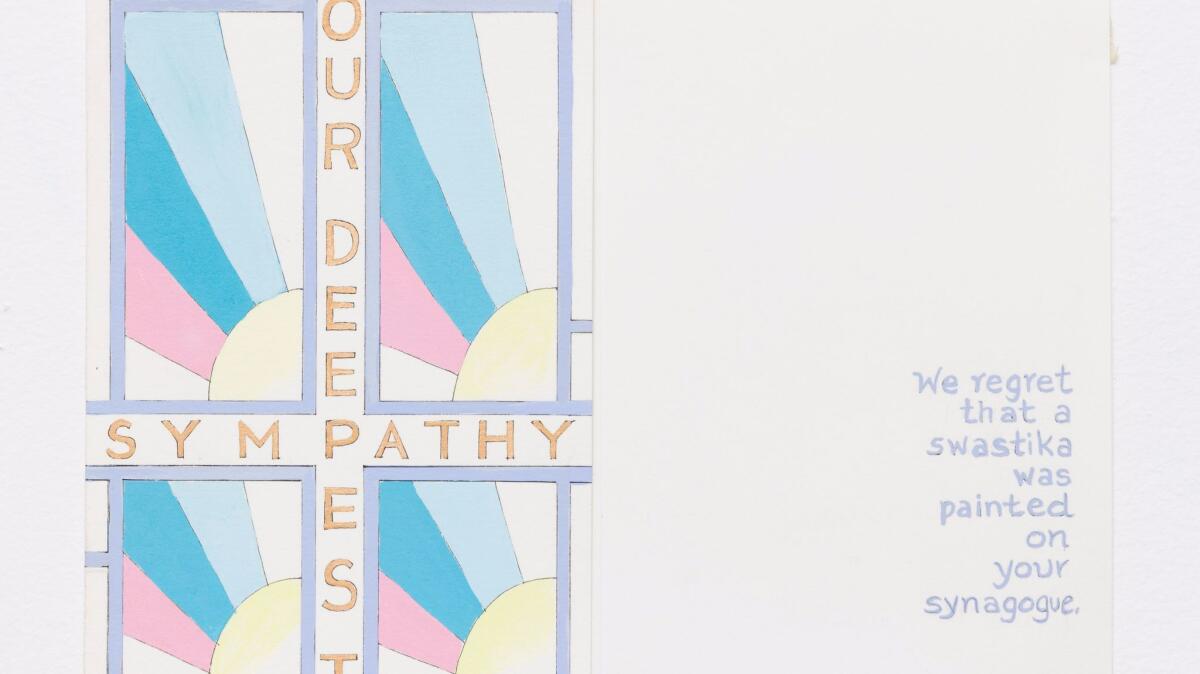

As in a greeting card store, these small paintings in ink and gouache are arranged by category, though most of the headings read more like debate topics (the economy, abortion, civil rights). “Sympathy” is perhaps the only familiar category, but Rothenberg uses it for condolences of a different order. "Sorry about the unusually high rate of cancer in your neighborhood," reads a card illustrated with a cloud of grimy factory exhaust that repeats over silhouetted houses. Other cards tender apologies for the disproportionate rate of death sentences handed to black people, and for swastikas painted on synagogues.

Based in L.A. and long ago an art director for an advertising agency, Rothenberg knows how to boil down a message to its essence, verbally and visually. Her words are concise and her graphics relatively simple, emblematic. Both serve the darkly absurd and sardonic. "People in poor countries are so lucky!" she writes, in a pseudo-primitive script, next to an image of emaciated, brown-skinned women. "They don't have to go on diets!" In another card, a woman in a skirt suit climbs a ladder beneath the words, "Hey Boss, it's ADVANCEMENT I'm after ..." And in the second frame, a man a few rungs below her gropes her rear, and the message concludes, "not ADVANCES!"

Rothenberg has made a practice of appropriating ordinary tools of communication and persuasion, inverting and subverting the content that passes through them. Prior to creating greeting cards, she developed a marketing campaign for Morally Superior Products (1980-90). Her ongoing re-creations of church signboards are brilliantly pithy, listing nightly meetings for the addicted, abused, traumatized, jobless, homeless and hungry, directly above the title of the week's sermon, invariably proclaiming America's greatness.

Rothenberg belongs to a long line of social satirists spearing the status quo. Among her closer relatives are Barbara Kruger and the Guerrilla Girls, cartoonist Roz Chast (herself a master of the barbed greeting card) and Stephen Colbert. Her work induces cringes, queasy laughter and sighs of every stripe — pain, shame, outrage. These are greeting cards that will never be sent, but they demand to be seen, and their messages received.

Charlie James Gallery, 969 Chung King Road, Los Angeles. Through Dec. 3; closed Mondays and Tuesdays. (213) 687-0844, www.cjamesgallery.com.

Born in Poland in 1887, Jacob Lehman immigrated to the U.S. during the First World War, settling in New Jersey and making a living as a woodworker and door-to-door salesman. At age 70, he retired to L.A. and started to draw, taking classes at a local rec center.

The 19 pastels on view in a quietly absorbing show at the Good Luck Gallery were among hundreds made in the decade and a half before his death in 1972.

Lehman followed a formula in these portraits and foliate still lifes, but his strange deviations and distortions of space and the body keep the images fresh. He typically divided the background of a picture into vertical bands of vibrant green, pink, gold, orange or turquoise, the center stripe broadening or tapering like a spotlight to concentrate attention on the central subject. The men and women, usually seated, face forward with neutral expressions turned sober, plaintive even, by peculiar eyes shaped like warped peapods.

One figure has a hairless head like a golden pear and an armless body like a bowling pin. Another appears to rest against a tipped-up table, arms crossed at the wrists upon the lap, a violet shape with one rounded edge describing a bent knee and one hard edge that seems to double as the corner of the table. For all the seriousness Lehman loads into those undulating eyes, his playful way with form turns each of his portraits into an idiosyncratic invention.

The Good Luck Gallery, 945 Chung King Road, L.A. Through Dec. 18; closed Mondays and Tuesdays. (213) 625-0935, www.thegoodluckgallery.com

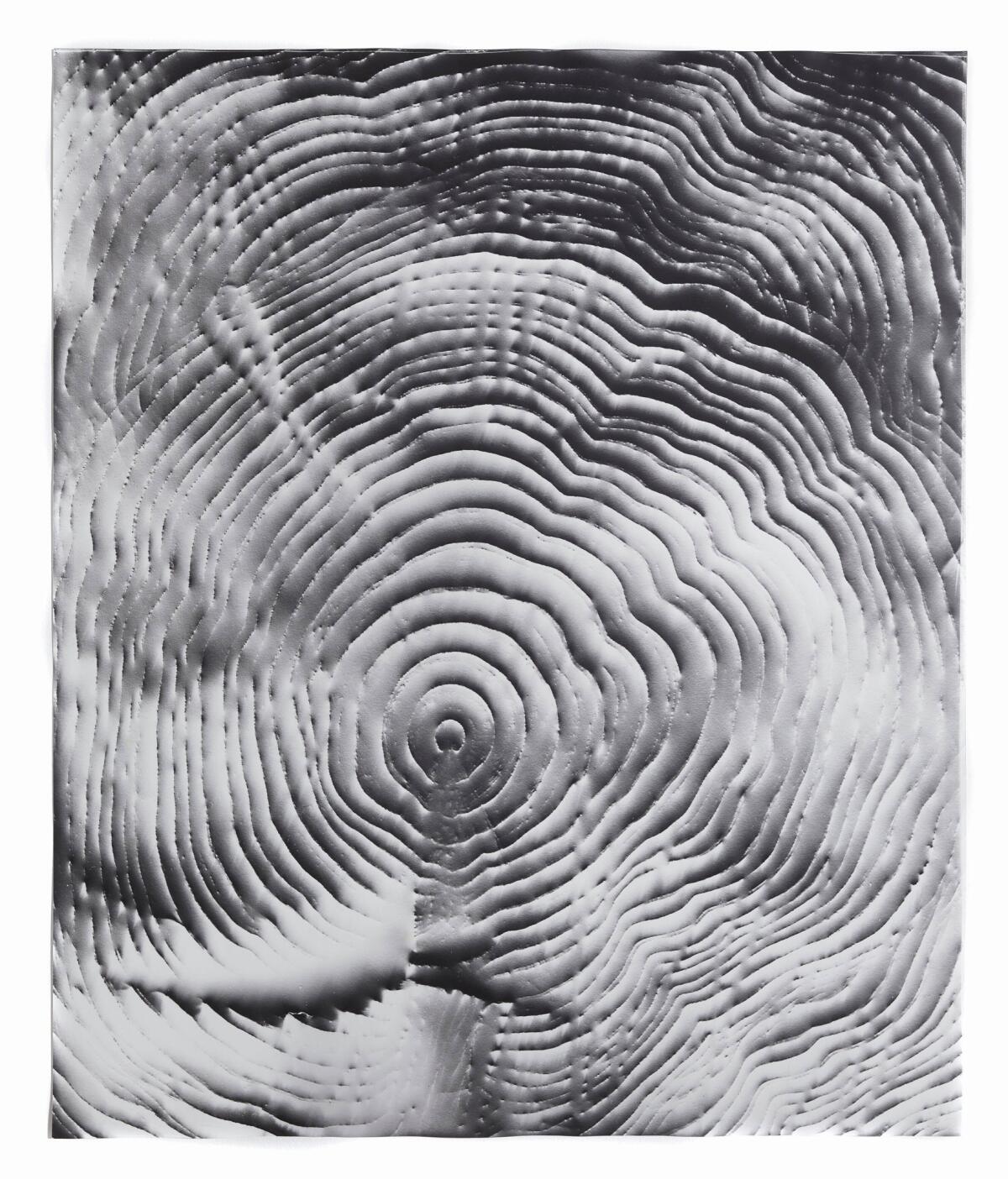

The earliest rubbings are believed to have been made of ancient Confucian texts engraved in stone and Buddhist texts carved in wood.

Klea McKenna's ravishing images at Von Lintel Gallery start with rubbings of tree stumps, made in the dark of night using photographic paper. She brings those rubbings into the darkroom and exposes them by flashlight, creating images with the self-evidentiary power of photograms and the evocative magnitude of sacred text.

The patterns of the annual growth rings, part of what McKenna calls "Automatic Earth," speak of rippling water and planetary orbits, of topographic maps and resonating echoes. "Born in 1969 (1)," two collaged rubbings of a 47-year-old cedar tree, is a mesmerizing koan, the visual equivalent of four strikes of a bell.

McKenna, based in San Francisco, brings a performative physicality to the photographic process. These works are records of her actions as much as they are reverential records of natural processes. Her exquisite photograms of spider webs after rain, made at night by flashlight, honor the labor of another maker, intuitive and efficient. The angular vortexes, woven chains of minute droplets, gleam moon white against depths of lush graphite, as in Vija Celmins' charcoal drawings and etchings of webs. Here, and especially in the images based on tree rings, McKenna engages wondrously with the materiality of time.

Von Lintel Gallery, 2685 S. La Cienega Blvd., L.A. Through Dec. 31; closed Sundays and Mondays. (310) 559-5700, www.vonlintel.com

Jack Hoyer's gratifying show at the gallery Moskowitz Bayse — his first in 30 years — induces a curious time warp. Who is this 70-year-old artist, only now emerging? How is it that these canvases look both old-fashioned and also current?

"Wilshire Center Building" (2015), like the show in general, is a quiet stunner. The view of a multistory apartment complex is instantly legible as a whole but abounds in slow-release peculiarities, revelatory details and telling contradictions. Hoyer makes the bland, blocky building the looming centerpiece of the canvas, a monumental anti-monument. Its washed-out-gray hulk is seen from across a tar-covered roof, through a screen of utility poles. The building's bank of windows reeks of anonymity, but up close, sameness yields to difference, through sill-mounted fans, bent screens, the tell-tale blue gleam of a television.

Hoyer, a longtime L.A. resident, bases each of his canvases on a composite photograph digitally stitched together from multiple views of a subject. The works stop short of photo-realism and adhere instead to a sort of photo-resonance, compositionally indebted to the snapshot's nonhierarchical aesthetic, yet subtly painterly, their surfaces muted but alive.

In "Big Bear Land Slab," Hoyer positions the viewer on the inside curve of a mountain road, beneath a telephone wire that unceremoniously slices the scene down the middle. He doesn't idealize or use ironically; he observes, meticulously. The everything-matters ethos of his practice levels the banal and the beautiful. His works testify to the power of deliberate — and democratic — attention.

Moskowitz Bayse, 743 N. La Brea Ave., L.A. Through Dec. 17; closed Sundays and Mondays. (323) 790-4882, www.moskowitzbayse.com

Follow The Times’ arts team @culturemonster.

ALSO

Times art critic Christopher Knight’s latest reviews

Thrilling new exhibition shows modern Mexican art is bigger than murals

At the Autry Museum, artist transcends the expectations of the label 'native artist'

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.