A small, but potent gesture in support of Tania Bruguera at the Hammer

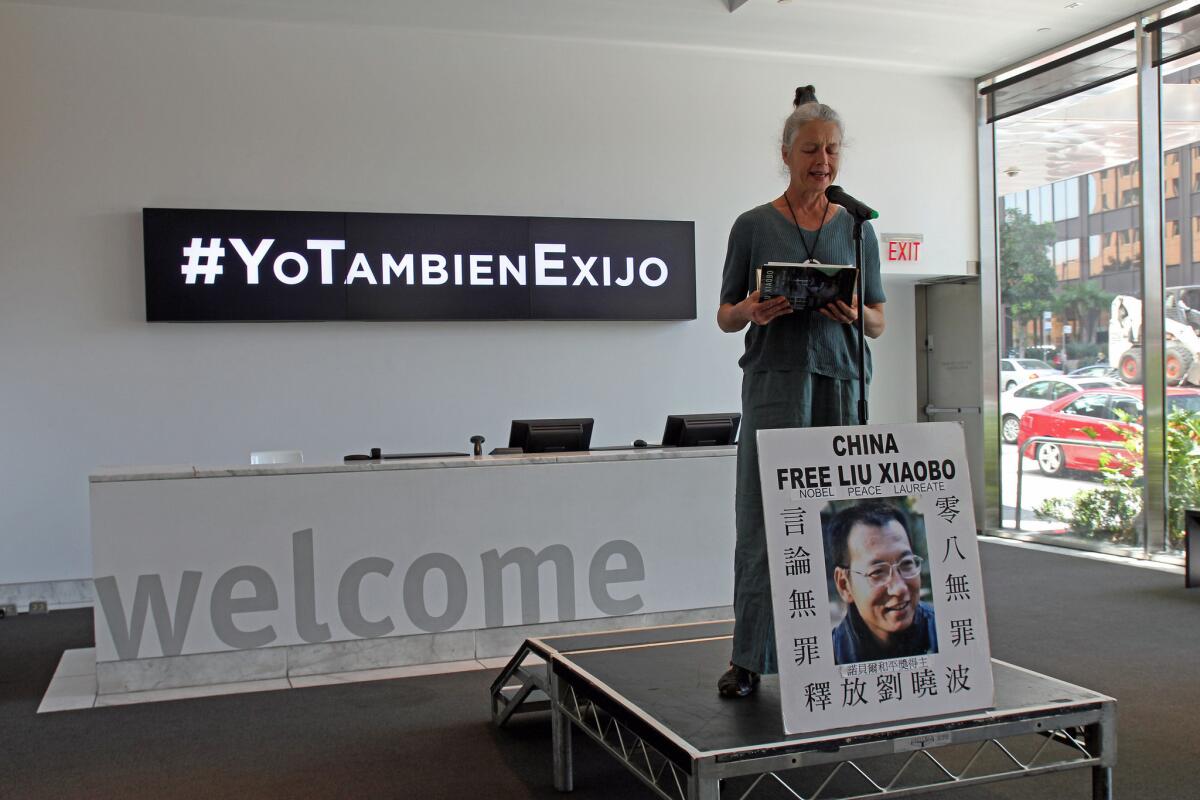

On Monday, the Hammer Museum re-staged “Tatlin’s Whisper #6,” a work of performance about free expression in honor of Cuban artist Tania Bruguera. Here, a participant speaks in honor of jailed Nobel Prize recipient Liu Xiaobo.

The crowd never grew beyond an estimated three dozen people. But the statements in support of Cuban artist Tania Bruguera — and freedom of expression in general — were strong.

Over the course of 90 minutes Monday afternoon, artists, curators and advocates of free speech gathered at the Hammer Museum to re-stage “Tatlin’s Whisper #6,” a work of performance in which members of the public are allowed to take to a podium to express themselves freely for a period of one minute. The re-staging of the work was done in support of Bruguera, who created the work, and who has been unable to leave Cuba since having her passport confiscated late last year.

On an improvised podium in the lobby of the museum, before a sign that read #YoTambienExijo (#IAlsoDemand), a slogan tied to Bruguera, audience members made statements about art, politics, protest and love.

One woman held a sign with an image of Chinese dissident artist Ai Weiwei that read: “China, Free Ai Weiwei.” Another had a placard bearing an image of Liu Xiaobo, the Nobel Peace Prize winner who is jailed in China for calling for government reforms. Curator José Luis Blondet of the L.A. County Museum of Art read a poem by Reinaldo Arenas, a Cuban poet who was jailed for his beliefs.

“As long as the sky exists / you will be my pain most noticeable,” he read. “My loneliness most tragic / my bewilderment unanimous / my perpetuous silence / and my absolute consolation.”

Perhaps the most moving statement came from Fernando Marquet, an Angeleno of Cuban origins who was held prisoner in Cuba in the early 1960s, and who said the performance was an important gesture of support: “This helps a lot to those who are in prison now, and I thank you.”

After the presentation, he told The Times, ”There’s nothing more difficult than for a political prisoner to think they are all by themselves. I was a political prisoner once and it gave hope to know that there were people out there who were thinking of me.”

Other presenters included L.A. installation artist Stephen Prina, who read the poem “The City” by C.P. Cavafy, and independent curator Cecilia Fajardo-Hill, who used her time onstage to urge members of the art world to consider what it might mean to participate in the coming Havana Biennial, given Bruguera’s continued legal limbo. Many speakers — like Michelle Papillion of L.A.’s Papillion gallery — read from from Bruguera’s “Manifesto on Artists’ Rights,” which museum staff distributed to the crowd.

The crowd was small, but enthusiastic. (The Hammer is generally closed on Mondays.) And many participants took to the podium a second time.

The performance was organized by the Hammer in collaboration with the arts nonprofit Creative Time, which staged its own version of the piece Monday in Times Square — an event that drew dozens of people, including New York cultural affairs commissioner Tom Finkelpearl, Performa festival founder Roselee Goldberg and artists such as Hans Haacke and Dread Scott. (Artnet has more.)

Bruguera was detained in Cuba at the end of last year for attempting to stage “Tatlin’s Whisper #6” in Havana’s iconic Revolution Square. She was released, but has been unable to leave the country since while the government still determines whether to file criminal charges against her.

Blondet says he participated because he was happy to see a museum raising its voice on questions of free speech in Latin America. But he was also intrigued by aspects of the performance itself.

“What’s important about this are the moments of silence,” he says. “You have these moments in which no one goes up. In which no one says anything. We have this open mike, yet we are not making a statement. And you ask yourself, ‘Why are we not taking advantage of the freedom we have?’ ”

Find me on Twitter @cmonstah.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.