What the 9/11 museum could learn from two Latin American memorials

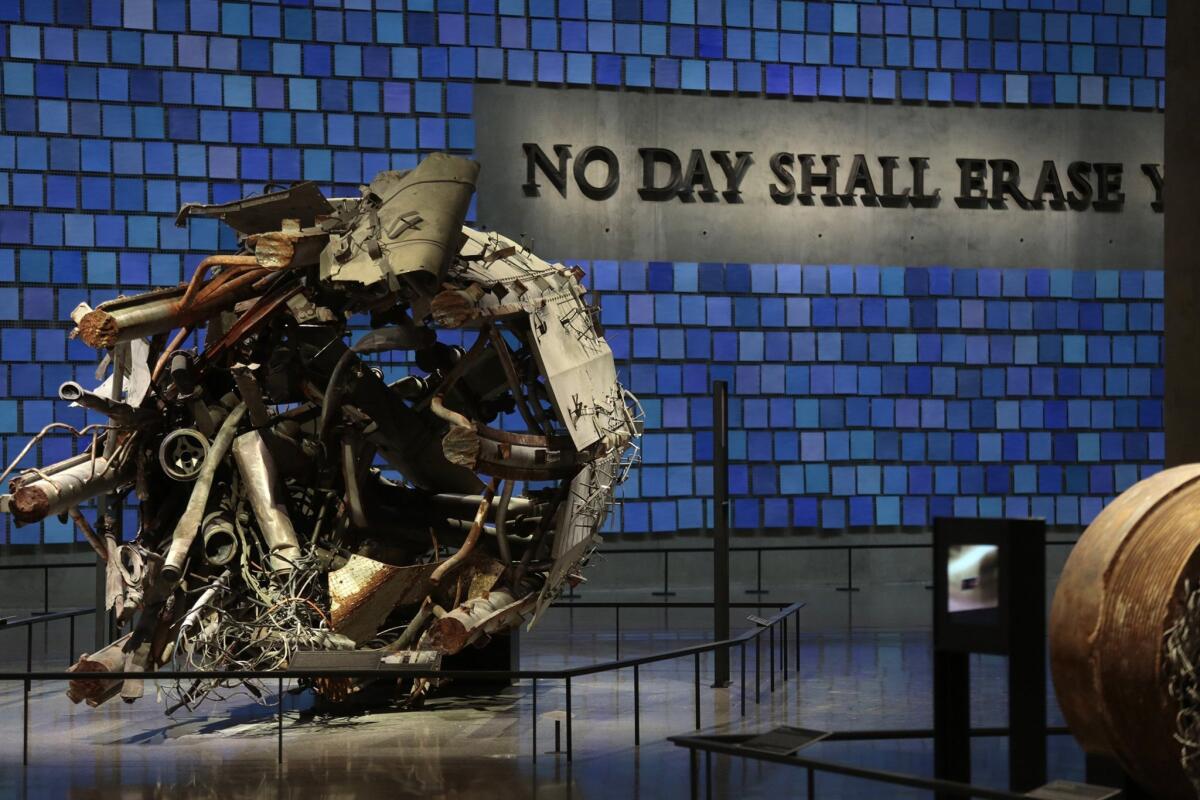

It is difficult to say at which point during my visit to the 9/11 Memorial Museum I went from somber to irritated. Was it at the umpteenth piece of mangled wreckage? Or at one of the overwhelming displays, cluttered with everything from a man’s watch to singed papers to a carbonized telephone, amid all the requisite news photos and portraits of the dead?

Maybe it was the barrage of audio and broadcast news — Matt Lauer and Katie Couric trying to make sense of an explosion at the World Trade Center playing on an endless loop. Or perhaps it was watching a tourist snap a picture of his child in front a smashed New York Fire Department (FDNY) truck. The cheesy gift shop — complete with FDNY jackets for dogs — left me feeling queasy.

As my colleague Christopher Hawthorne wrote in May when it first opened at New York’s ground zero, the 9/11 Memorial Museum isn’t a place that leaves you any “space to be alone with your thoughts.” And he couldn’t be more right on.

Entering the museum is a procedure that requires a TSA-style full-body scan. The exit is an escalator ride that douses the visitor with bagpipe music. (Yes, bagpipe music.) The relentless multimedia-ness of the whole experience made me more frazzled than reflective.

This is unfortunate, for 9/11 is a day that has deep political and historical resonance for this country. It resulted in the deaths of nearly 3,000 people. It has been at the root of a bloody war, and it unleashed a climate of heightened security from which we have yet to emerge. (Hence those full body scans at the entrance to the museum.)

For me, it also has profound personal resonance. I lived in Manhattan on September 11. And while I didn’t lose any loved ones in the attack, I feel my chest tighten any time I think too much about the events of the day: the acrid smoke, the pedestrians covered in ash, the bits of paper detritus that floated like confetti through the air.

Above all, there was the silence. On the afternoon of the attack, Manhattan was sealed off from the rest of the world. And without traffic, it grew eerily quiet. No honking horns, no roaring garbage trucks, no screaming kids in the street. Just the occasional sound of sirens as they made their way down the avenues.

The 9/11 Memorial Museum may show (and show again and again) every last detail related to the attack, but it fails to evoke the surreal qualities of that day. And it fails to set a mood that might get a visitor to reflect thoughtfully about that carnage and its consequences. Instead, the aim seems to be overstimulation at all costs.

There are better, more meaningful ways of memorializing the dead. Certainly, Maya Lin’s Vietnam War Memorial comes immediately to mind. But I also think of a number of Latin American memorials that I’ve visited in recent years, installations that take a political tragedy rife with death and turn it into more than the sum of its parts.

The first is the Museo de la Memoria (Museum of Memory) in Santiago, Chile, which pays tribute to the victims of the country’s military regime that took power on Sept. 11, 1973. (We’re not the only ones with a 9/11 to mourn.) From that day until a democratically elected government came into power in 1990, an estimated 3,000 Chilean citizens were disappeared and another 40,000 were imprisoned or tortured or both, according to Amnesty International.

The museum that marks this history is appropriately solemn — visitors descend into a large, rectangular prism designed by Brazilian architects Estudio America before emerging into several stories of galleries. These chronicle the history of the military regime and its abuses. And although the installations aren’t perfect (there is too much unimaginative presentation of newspaper clippings), the museum is spacious and uncluttered and features quiet, dim spaces that allow the viewer to process everything they have seen.

The highlight is a balcony on the third story that overlooks a wall filled with pictures of the missing and the dead, all arranged as if it were a shrine. In that space, there is nothing else — no names, no numbers, no facts, no audio — only the faces of the victims peering back at you from across an empty gulf. During my trip through the museum, visitors frequently stood or sat quietly before this improvised chapel. It was extraordinarily moving.

Another memorial I visited in Peru proved that it is possible to create a sense of solemnity with the most limited of means. Until the more elaborate Lugar de la Memoria (Place of Memory) opened in Lima last month, a years-long temporary exhibition housed at the country’s Museo de la Nación (National Museum) paid tribute to the roughly 70,000 lives claimed by Peru’s internal conflict (a morass of fighting between various armed groups and the heavy-handed Peruvian government that dragged on for more than two decades).

That installation, called “Yuyanapaq” (“to remember” in Quechua), couldn’t have been simpler: an array of stark, white galleries with polished concrete floors featured geometric arrangements of mostly black-and-white photographs that chronicled some of the most significant moments in the conflict.

A final room contained images of a handful of the disappeared, with audio elements taken from testimony before Peru’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission. The sound element bordered on the inaudible, which meant that you had to almost strain to listen. As a result, viewers stood quietly, listening to the terrible stories of people who had been arrested by the government, then never seen or heard from again.

“Yuyanapaq” was a simple exhibit that required viewers’ focus and commitment. And for that reason it never failed to be contemplative. It was a space that, with the most basic of tools — well chosen photos, wall text, a bit of sound — inspired deep reflection. (I’m hoping the new memorial, a fancier sand-colored structure by Barclay & Crousse, featuring a variety of exhibits, stayed true to the installation’s original effect.)

These memorial museums worked because they weren’t given over to multimedia flash. They also weren’t trapped by a mind-deadening literalism. They didn’t overstuff their galleries with object after object after object. And they didn’t feel the need to recount every last detail about their shared tragedy. (That’s what the history books are for.)

Instead, they stuck to key happenings, providing plenty of space in between for viewers to bring a bit of themselves into the exhibition. Even years after seeing these South American memorials, I still find myself reflecting on the experience, on what all of those deaths could have meant. The 9/11 museum, sadly, has yet to have such an effect.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.