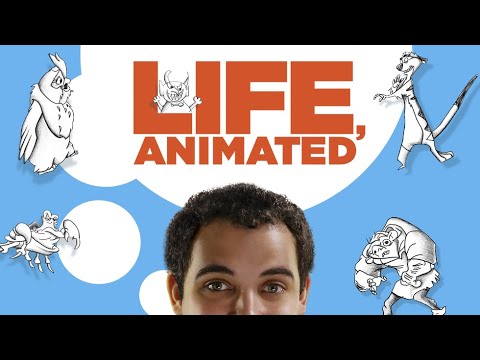

Documentaries ‘The Eagle Huntress’ and ‘Life, Animated’ explore the worlds of two very different young people

Two documentaries shortlisted for the Oscar nominations, “The Eagle Huntress,” directed by Otto Bell, and “Life, Animated,” from Oscar-winning director Roger Ross Williams, showcase two remarkable young people on their own sorts of hero’s journey.

Each overcomes mammoth hurdles: Aisholpan Nurgaiv, in “Eagle Huntress,” becomes the first female to learn to hunt with eagles in 12 generations of her Kazakh family, and Owen Suskind, in “Life, Animated,” is a young man with regressive autism who teaches himself how to communicate and interact with the world via Disney films. Here, the directors take us through their documentaries.

“The Eagle Huntress”

The film stems from a photograph taken by Israeli photographer Asher Svidensky originally on the BBC. As your first film, what made you know this was the story you had to tell?

A lot of people saw that photograph I now know. I still remember working away in my cubicle in NYC and thought the photo was just otherworldly; could this be a film? What is the story? Once I dissected the photograph: incredible setting in the Altai Mountains; a young girl training with the largest species of golden eagle in the world and Aisholpan, the heroine, smiling and looking so angelic, I moved fast. I found the photographer on Facebook, we had a Skype call, and very quickly I had him and me on a plane to Mongolia to meet the family.

Kenneth Turan reviews ‘The Eagle Huntress’.

At what stage did you realize you had something so extraordinary?

That first afternoon [meeting the family]. There’s a small window of days to remove a baby eaglet from its nest and that afternoon the father was taking Aisholpan to retrieve one. He asked, “Is this something you’d be interested in filming?” I wasn’t prepared but we made it work and when I saw that little girl — I mean if I had Hollywood’s best costume and set designers I couldn’t have done anything better. This girl with a ribbon in her hair scaling and rappelling down the side of these mountains and hypnotizing the baby eagle with her hands and staring down the mother eagle circling overhead, I just thought, “This is something really quite remarkable.”

Whose idea was it to have the kind of Greek chorus of elder naysayers bashing the idea of a girl becoming an eagle huntress?

It came to me as I interviewed other village eagle hunters, and they all said the same thing. When asked if there was a female eagle hunter: “Jok, Jok, Jok!” [No, No, No!] After Aisholpan won the annual festival, beating out 70 older and more experienced male eagle hunters in the key speed contest, in which the eagle must fly from a nearby mountaintop to the hunter’s out-stretched arm, with a record-breaking speed of five seconds [her father, a three-time champion eagle hunter, did it in 11 seconds] they then said, “OK, but can she hunt? That will be their real test.” Which, of course, she did and which was the important part for Aisholpan. It’s why I didn’t end the film with the big rah-rah victory circle, but with her later literally riding off into the sunset with her father.

What did Aisholpan and her family think when they first saw the film?

It was at Sundance and it was nerve racking, but thankfully they loved it. The Comanche people, who feel a connection to Mongolia, were kind enough to bring their eagle and there was a beautiful smoke and naming ceremony where they gave Aisholpan a Native American name: She Who Prospers with Eagles. It was quite emotional.

How has she taken to this newfound global celebration — she appears somewhat shy on film?

I’m pleased to say there hasn’t been a big culture shock. They haven’t moved out of their ger [nomadic dwelling]; they’re not moving to the city anytime soon, though things have changed. She got a scholarship to one of the best schools in Mongolia and I made them a participant in the film (when it sold to Sony Picture Classics) and she’ll be able to study medicine wherever she wants in the world.

“Life, Animated”

You worked with Owen’s dad, Ron Suskind, a Pulitzer Prize-winning author, for years before the film. When did you realize Owen would be a good film subject?

When Ron was writing his very personal book about his son, he came to me and said, “I think this would make a great film.” I totally, wholeheartedly agreed. I knew about the Disney Club where Owen’s classmates learn about life from classic Disney films that help them make sense of the world and what it means to be human and to connect with other people. To me, this is about the power of story, which is literally Owen’s life. Each single moment of his day and every challenge he faces, he finds a Disney clip and story to help him make sense of the world.

So he’s like a computer data spreadsheet of Disney film?

Absolutely. He knows every single voice from every film from the ’50s onward and can do all the voices and different characters and knows every single line, ever. He also knows every voice-over actor and every single job, he’s a walking “Wonderful World of Disney” IMDB.

Had you interacted with an autistic person in a significant way before?

I had no knowledge of autism. And so the challenge for me was to get inside his head and tell the story from his perspective. I came up with using the Interrotron [an interviewing device developed by documentarian Errol Morris] and I’d pop up on a screen with a lens behind me and Owen, who is very comfortable with screens, looked directly at me and talked. He’s the only one in the film looking directly at the camera and audience and tells his own story.

Is Owen comfortable with his newfound fame?

He loves it. It’s amazing how comfortable he is with his new role. The other day at a Q&A, someone asked him how he felt being a celebrity and he said, “I’m not a celebrity; celebrities are out for themselves. I’m just someone who is being celebrated this year.” I’d say Owen is a pure person. And so people respond and react to that. With audiences, I call it the Owen Effect. People are beside themselves, yelling and on their feet and he’s high-fiving and takes the stage. He does a Disney voice and says, “I feel the love in this room.” If he wants to belt out a Disney song, he will. It’s magical.

What have you learned about people with autism that you didn’t understand prior?

Owen is someone totally sensitive to everything around him. I used to think autistic people lacked empathy — Owen has more. It’s how they process and express it that’s different. He also doesn’t have the bubble around himself we all have; worrying what other people think. He’s not self-conscious at all. So Owen is who he is. It’s 1 in 44 boys; a really high number born today on the autism scale and it’s a whole population of people have been left behind who, as Owen explains it, “people look past on the street.” I hope this film helps change that.

Your films seem to showcase alienated outsiders; is this something that stems from your past?

Absolutely. I grew up feeling a sense of alienation as a black gay man and I was in my own fantasy world. For me, every film is personal, it has to be, to tell a great story. I didn’t have role models; I didn’t have people like me when I was growing up. I didn’t see them on screen. I didn’t even have them in life. I had a single mother, very poor family, in an environment where I shouldn’t have thrived, the odds were against me and yet I succeeded …

See the most read stories this hour »

ALSO:

The documentaries ‘Tower’ and ‘The Ivory Game’ examine very different kinds of killings

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.