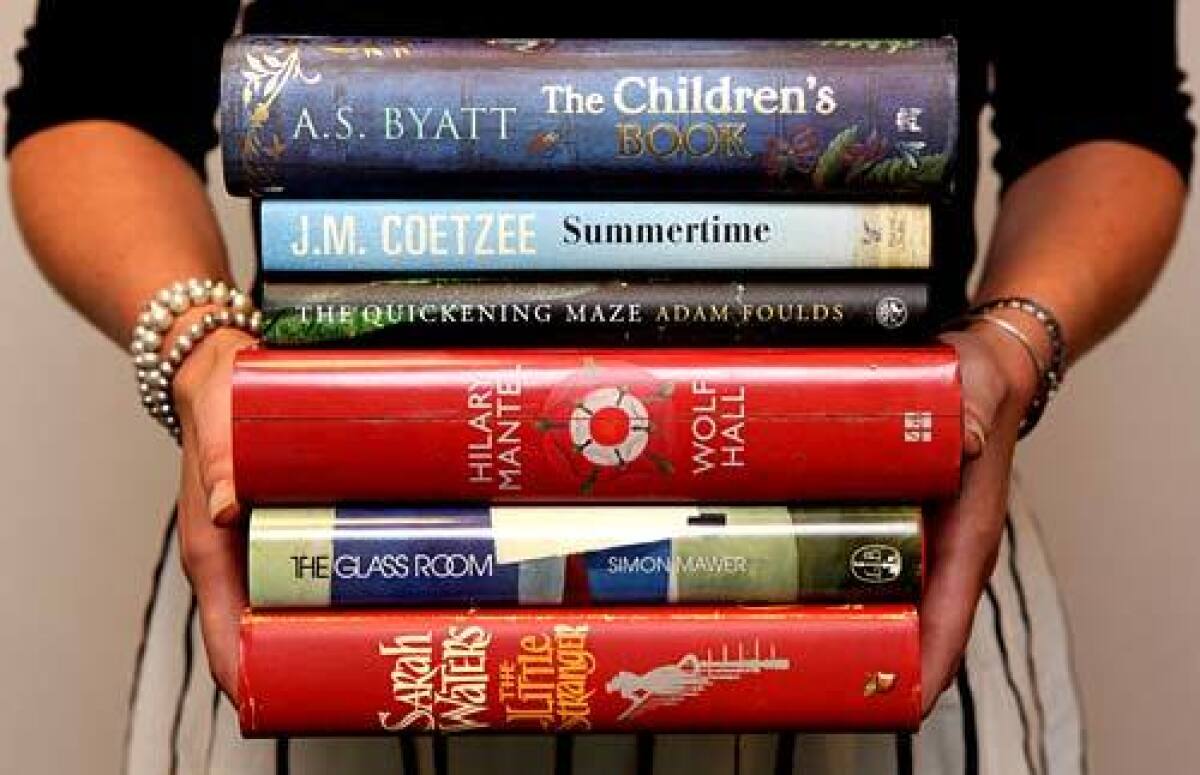

‘The Children’s Book’ by A.S. Byatt

The Children’s Book

A Novel

A.S. Byatt

Alfred A. Knopf: 680 pp., $26.95

A.S. Byatt writes about English society at the end of chrysalid stages (there’s a naturalist metaphor I’m sure she’d appreciate) -- when hidden forces are about to burst the norms and conventions of an age, sometimes producing a butterfly, but not always.

You find these transforming pressures in the tetralogy she started with 1978’s “The Virgin in the Garden” and ended with 2002’s “A Whistling Woman.” It’s there in “Possession,” her 1990 bestseller about a hidden Victorian romance, and, since we’re talking about butterflies, it takes literal shape in 2003’s “The Little Black Book of Stories”: A monstrous worm in “The Thing in the Forest” isn’t just a metaphor for the chaos of World War II -- it looks like larva escaped from a cocoon.

A boy in the country

“The Children’s Book” is another portrait of a time of imminent change -- in this case, the years when the Victorian golden age depreciated into Edwardian silver and then, with World War I, into an “age of lead.” The novel’s early sections take us to Todefright in 1895, the country home of the Wellwoods, who welcome a lost youth into their midst. That youth, Philip Warren, is a child of the factories who dreams of being a potter like the temperamental artist Benedict Fludd who lives not far from Todefright. Philip’s circumstances so affect Olive Wellwood, a successful writer of fairy tale stories (he seems, to her, to embody the lonely children in such stories), that she invites him to celebrate Midsummer’s Eve with them.

These scenes contain everything Philip -- or any reader, for that matter -- could ever dream of: a romantic country house “full of smells of cooking”; neighboring woods containing treehouses and other surprises; garden parties with “trestle tables on the lawn” and “little cosy, or conspiratorial, groups of chairs in picturesque places”; puppet shows; leisurely intellectual discussions -- all meticulously imagined by one of our very best contemporary writers. It is also a St. Martin’s summer -- gilded but short-lived. Do not misunderstand this golden glow, Byatt warns. As Olive writes, in one of her tales, “there are ratholes everywhere, even in palaces.”

Even in Todefright: Olive’s husband, Humphry, gives up a secure bank job to be a writer, freelancing for any and every cause. Writing work isn’t as steady as he thought, however -- soon the ground beneath their feet fissures as the bills start piling up. For Olive, though, these cracks reveal a subterranean world of elves and fairies -- now the stories she writes turn into a vital source of family income.

We follow Olive’s efforts to keep her family intact through financial and marital crises; we see the sexual stirrings, confusions, embarrassments of the young and the stark differences between families. Olive manages her brood with the help of her sister Violet, but there are other reasons, aside from helpfulness, why Violet is there. The London Wellwoods are a smaller unit than their country cousins but just as fragile. Prosper, the patriarch of the Cains, regrets his widowerhood most because his daughter Florence doesn’t have a maternal presence to guide her; the Fludds are an absolute nightmare -- a household of sleepwalkers and timid personalities, everyone at the mercy of Benedict’s wild moods, though Philip’s earnestness helps him to fit in as Benedict’s apprentice.

Though crises afflict these characters -- infidelities and their diapered consequences; Olive’s son Tom’s harrowing school experiences; his sister Dorothy’s discovery about her true identity; the predations of Herbert Methley, the story’s scholarly satyr; Fludd’s increasing resemblance to mad King Lear -- what precipitates drastic change in this novel is war. Byatt captures the modern world’s uneasy crawl from its cocoon with a commanding section on the Paris Expo of 1900, in which fragile works of art are eclipsed by the “two largest exhibits . . . Schneider-Creusot’s long-range cannon and Vickers-Maxim’s collection of rapid-fire machine guns.” We know where this world is headed.

What Byatt has said about “Middlemarch” is true here: “It is possible . . . to invent a world peopled by a large number of interrelated people, almost all of whose processes of thought, developments of consciousness, biological anxieties, sense of their past and future can most scrupulously be made available to readers. . . . “ “The Children’s Book” is rich, expansive; the cast is large and the pace gradual -- if you’re impatient for a fast plot, maybe you’d better read a mystery or watch some TV instead.

Her observation of the minutiae of moments in her characters’ lives is as intense as Matty’s studying of red ants in “Morpho Eugenia” (in 1992’s “Angels & Insects”). If she hadn’t been a writer, Byatt should have been a naturalist like W.H. Hudson. Or else she should have been a painter. At times she captures the natural world with the precision and neutrality of Constable -- “at Dungeness, in mixed, squally weather . . . achingly bright patches of light off the water were succeeded by whipping winds and draggled clouds streaming over the sun” -- at others, you get the feeling details have been assembled with the cunning of Poussin.

Stories in stories

“Cunning” also applies to the novel’s stories within stories. Where the rest of us would gladly face rats and bloodtides (these are in one of Olive’s tales) to create just one of her narratives, Byatt is a spinner of multiple tales, adding gorgeous layers and dimensions to this fictional world -- much as she did in “Possession” and elsewhere. Splendid in themselves, these stories comment on the novel at large. The narrative of “Tom Underground,” for instance, a tale of a young prince’s search for his stolen shadow, stops as Tom Wellwood goes away to school -- Olive’s imagined realm of perilous mines shifts to the cruel world Tom enters.

Late in the novel, Prosper’s son Julian uses his lyric gifts to mourn the dead of World War I -- Byatt provides us with a sheaf of his poems.

It is another tale, however, that says the most, I think, about what Byatt achieves in “The Children’s Book.” Whom does this title refer to? Olive’s story “The People in the House in the House” is a sly, irony-steeped tale of a little girl who captures fairies and imprisons them in her dollhouse, only to be captured herself and imprisoned by a giant child. In watching Byatt’s characters, especially parents who insist on clear paths for their young though their own lives are anything but clear, the simple message of that story -- that no one is ever in total control -- shows “The Children’s Book” is a title that applies to everyone.

Owchar is deputy book editor of The Times.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.