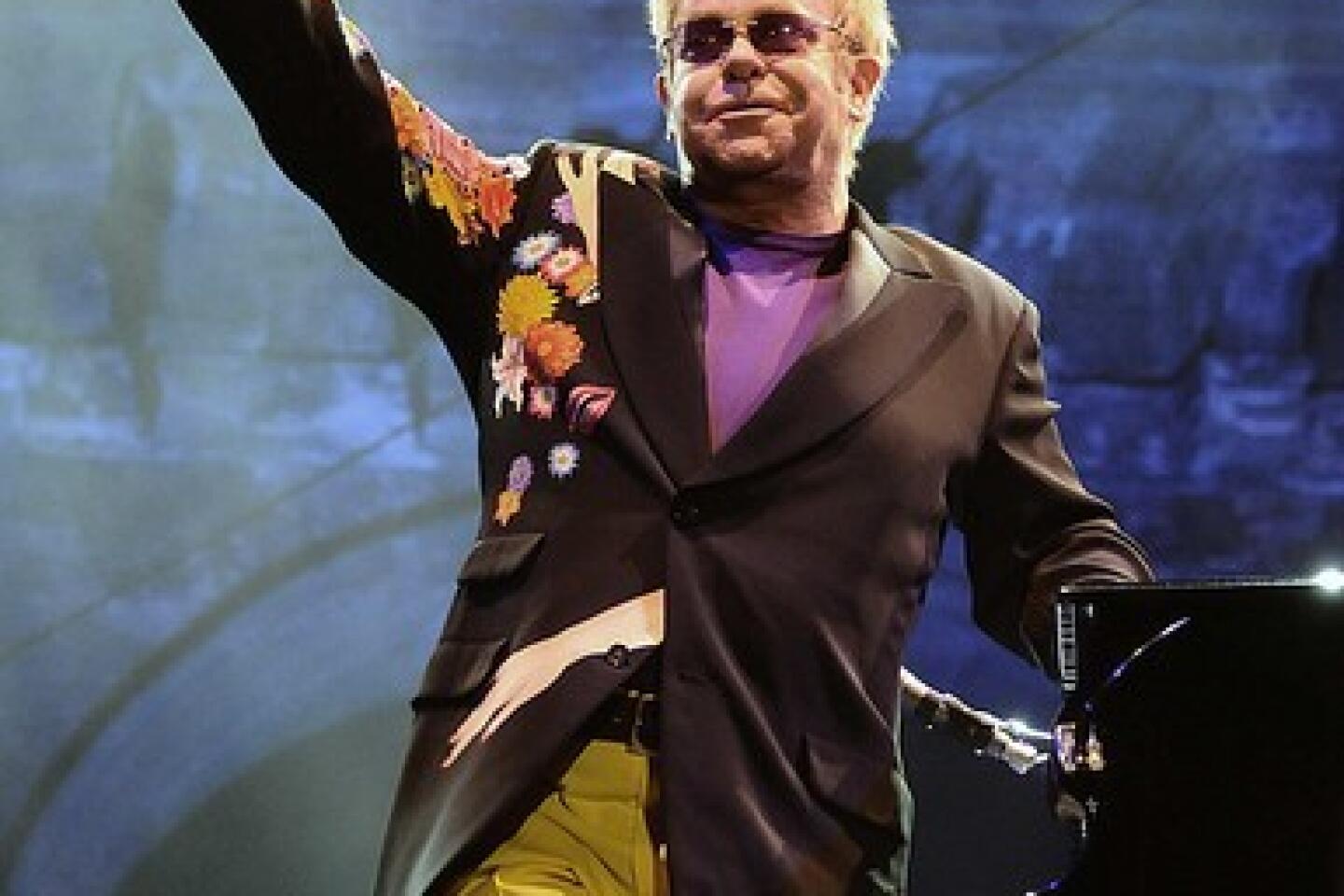

Showcasing an album in concert

When Elton John stopped in Los Angeles this month on his latest concert tour, he came in with one of the biggest storehouses of hits in pop music history. But instead of diving headlong into his catalog, he and his old friend Leon Russell devoted the centerpiece of their time together at the Hollywood Palladium to a complete performance of their new duet album, “The Union.”

The performance ran counter to several bits of conventional wisdom about pop music today: Veteran artists must rely in concert on their hits to satisfy fans, the album format is dead or dying in the era of the downloadable individual track, and the ability and willingness of the pop audience to focus attention on extended musical works is shrinking by the minute, thanks to the explosion of music instantaneously available at the click of a mouse or iPhone app.

The John-Russell show was by no means an isolated incident.

A few weeks earlier, Velvet Underground alumnus John Cale played his 1973 album, “Paris 1919,” from beginning to end in concert at UCLA. On Monday and Tuesday, Roger Waters encamps at Staples Center for a full-scale re-imagining of Pink Floyd’s 1979 magnum opus “The Wall.”

And the efforts appear to be snowballing.

Van Morrison, Bruce Springsteen, Lou Reed, Brian Wilson, Iggy Pop and Cheap Trick have all done it. The trend isn’t strictly the domain of classic rockers, either: alternative, indie, country and punk musicians who have taken to the idea include Weezer, Lucinda Williams, Snoop Dogg, Nine Inch Nails, Rosanne Cash, Bob Mould, Television, Social Distortion, Tool, Redd Kross, Sonic Youth, Ben Folds, Ben Kweller, Wu-Tang Clan and A Tribe Called Quest.

Sparks, start to end

The Guinness Book of World Records winner in the field would have to be long-running L.A. experimental pop duo Sparks, which played its entire catalog of 21 albums over 21 nights two years ago in London leading to its then-latest effort, “Exotic Creatures of the Deep,” presented on the final night, from beginning to end, of course.

If the album format is dead, a lot of musicians didn’t get the memo.

“I think it’s very healthy,” said John. “We live in such a time of ADD attention deficit, when people hardly listen to something for more than 30 seconds before they switch channels. You don’t go into an art exhibit and look at one painting; you look at 16. I think it’s good to listen to a body of work.”

After nearly half a century in which the technology of recorded music put the emphasis on individual songs three or four minutes long at most, from 10-inch 78 rpm discs up through the 7-inch 45 rpm single, the advent in 1948 of the long-play album capable of offering 40 to 45 minutes of music split over two sides of a vinyl LP allowed musicians of the ‘60s to significantly expand the scope of what they offered listeners.

Throughout the ‘70s, ‘80s and ‘90s, the album, even after CDs arrived in 1983, was the dominant form for musical expression in the pop music world. When the ability to share music over the Internet arrived in the late ‘90s, all that began to change, and in a few short years, the individual track has reigned once again. But many musicians refuse to let go of the medium that allowed them to explore an extended musical thought.

The live presentation of entire albums isn’t so much happening in opposition to changes in music but in response to and perhaps even in tandem with those changes. Music fans can more easily than ever assemble individualized playlists on their computers or MP3 players — giving them unprecedented freedom of choice, while rendering irrelevant musicians’ preferences for the sequencing of songs on an album.

But there’s still no “shuffle” button to push at a concert. “Artists craft live shows to provide an experience the audience can’t get at home,” said Chris Sampson, head of USC’s pop music performance degree program. “Not only has the conversion to ‘cherry-picking’ singles changed buying habits, it has also changed listening habits, with people listening while multi-tasking rather than sitting themselves in front of a hi-fi and taking in an entire album. A live performance of an album now offers a new experience for the audience and makes the concert more of a true ‘event.’”

There’s also the harsh reality of the recent downturn in the live music market, which had remained relatively robust even as the public’s appetite for buying CDs and MP3s has eroded dramatically over the last decade. “The economy has really had an effect; we’re guessing business is about 15% off compared to last year,” said Gary Bongiovanni, editor of Pollstar, which tracks the concert industry. “To impress fans to come out and see you one more time, it’s helpful if you give them something special. It’s not the kind of thing you can do over and over, but it’s a great way to really rally the fan base.”

Musicians have myriad motivations for taking on a full album live.

“It feels like there’s a growing demand from our audience to hear more of the album tracks from ‘Pinkerton’ and our first album, ‘The Blue Album,’” Weezer’s Rivers Cuomo said of the two albums the group is performing on its current tour. “At the same time, it feels we’ve been doing the same sort of greatest-hits set for a while, so we want to try something different. We’re doing it both for our own excitement and for the people coming to see us.”

Long Beach rapper Snoop Dogg played his 1993 “Doggystyle” in full in concert last year because “I felt that album changed the face of music, and fans have been asking me to come back and perform it. I never had the opportunity, because I had some legal trouble when that came out. But now I could give people a piece of something they always wanted.”

In the late ‘90s, Cheap Trick mapped out a strategy developed by the group’s manager, David Frey, in which the band played each of its first three studio albums on three successive nights in each city it visited.

“It was a bit of a gimmick, really,” bassist Tom Petersson said. “But it seemed like a good idea, and it was really interesting to go back and learn these songs, a lot of which we’d never played live before. Some were never popular, just things we did in the studio.”

Jam band Phish has made a tradition out of performing a full album by another artist each Halloween. “It’s almost like going to music camp for a month of every year,” group leader Trey Anastasio said. “You start to hear the influences pop up when you’re playing. … When we did [the Rolling Stones’] ‘Exile on Main St.,’ I didn’t care about trying to make it sound exactly like the album. I wanted to get inside of their heads, and inside that era, to find out what made that music so powerful. It’s really studying what makes rock music, popular music, tick.”

A body of music

Singer-songwriter Lucinda Williams said the same thing happened to her in regard to her own body of music when she worked up five albums to play live over five nights to mark her 30th anniversary as a recording artist.

“It’s good to go back and respect your early work,” she said. “For every song I’ve written, there’s going to be someone who loves that song. It’s good not to just leave them behind and never go back and look at them. And you can learn something. My ‘Car Wheels [On a Gravel Road’ from 1998] album was the pivotal one for me, and I was thinking, just asking myself, ‘What was it about those songs that drew people in? What can I learn from that?’ …Ultimately, though, it gave me this freedom to do whatever I wanted to do.”

Most practitioners, however, agree it also takes the right artist and the right album to make it work.

“Audiences sometimes have to be fed new material, almost trained to accept new material,” said British guitarist Richard Thompson, who took the next step by mounting a short tour this year featuring a full album’s worth of new material, recording the live performances and releasing it as his new album, “Dream Attic.” “Some artists who have a couple of classic hits find that they are unable to retrain their audiences, so they tend to fall back on what the audiences want to hear. It’s very static-repertoire syndrome.”

That’s the syndrome Sparks sought to demolish with its “21 Albums in 21 Nights” shows in London, where the idiosyncratic group formed four decades ago by brothers Ron and Russell Mael has maintained a strong following.

“We’re not interested in doing nostalgia,” Russell Mael said. “We thought, ‘What could we do to focus attention on our current album that probably no other band could ever do on this sort of scale?’ Any band that would have 21 albums in their repertoire wouldn’t have the focus, the hunger and the kind of daring to want to do it.”

Added Ron Mael, “In one sense, with iTunes and all that, it’s moving in the other direction, where people are choosing just to listen to the strongest song off an album and have no interest in an album as an entire piece. They’re not interested in the bigger picture.”

And the bigger picture is exactly what musicians are after by taking on large-scale works in concert.

“If we can do anything to revive the strength of the music and help bring the business back, something that really has to be thought about is how to bring the value back, how to restore the loyalty, loving your artists,” said producer Hal Willner, who worked with Lou Reed and artist Julian Schnabel in stagings of Reed’s 1973 “Berlin.” “The question you have to ask anytime something like this comes up is: Is it good or bad for music? It wasn’t my line about music losing its value. Doing these albums, these whole pieces, it’s just good for music.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.