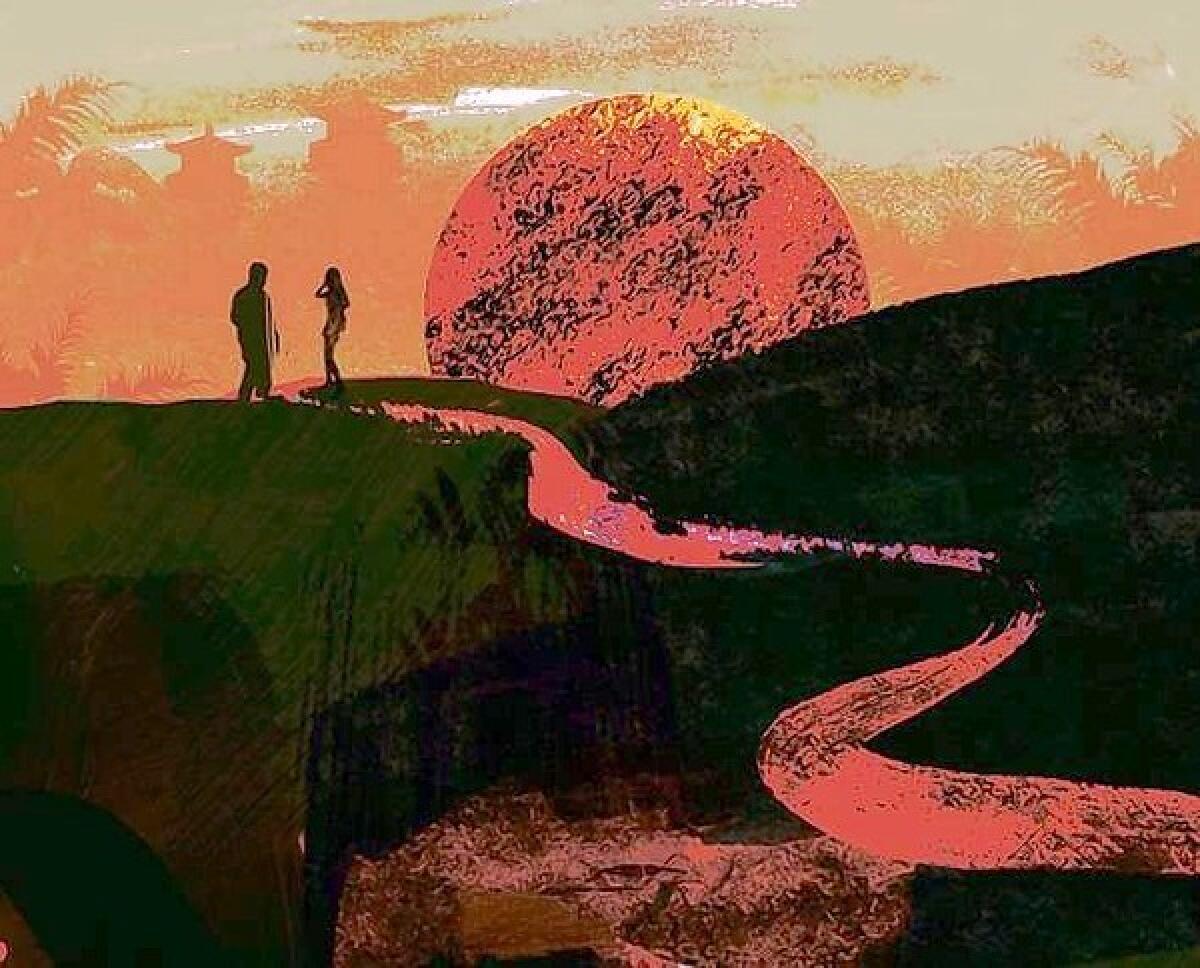

Book review: ‘Girl by the Road at Night’ by David Rabe

Girl by the Road at Night

A Novel of Vietnam

David Rabe

Simon and Schuster: 230 pp., $23

It was a grant that determined the form David Rabe’s writing on the Vietnam War would take after he was discharged from the Army in 1967.

The money was for playwriting, and with it he began the quartet of plays that would make him famous: “The Basic Training of Pavlo Hummel,” “Sticks and Bones,” “The Orphan” and “Streamers.”

“But oddly enough, it was a novel rather than a play that I wanted to work on,” he wrote later. Still, even when he was in Vietnam, trying to keep a journal, he found it difficult to convey in prose what he was experiencing: “In no way could I effect the cannon, the shuddering tent flaps. In an utterly visceral way, I detested any lesser endeavor.”

At age 70, Rabe has at last penned his Vietnam War novel, and it is not the book he might have written four decades ago. He does not attempt, really, to effect either the cannon or the tent flaps. “Girl by the Road at Night” is spare, stark, muted, more observational than immersive, and vaguely haunted. It is also conscious in a way that youth isn’t of the callowness of the two characters at its center and of the mortality of old men.

This is a sharp-edged boy-meets-girl story complete with longings of the heart but stripped, as Rabe’s plays are, of the conventional war-story veneer. Not for a moment does it confuse armed conflict with glory or forget the disorienting isolation of being far from home and family amid an ever-changing cast of strangers, a circumstance that applies to the girl in the story as well as the boy.

The girl is Quach Ngoc Lan, the daughter of a Vietnamese farmer who went to work in the fields one morning and drowned there. Tiny and capable of ferocity, Lan works now as a prostitute, servicing GIs at a roadside brothel: “They are indecipherable, all of them; their moods shatter, cruel and dangerous as the beer bottles that break.” More than a few think nothing of beating and threatening Lan. Sometimes they don’t bother to pay, but part of what she does earn she sends to her family. She is as much at the mercy of war’s vicissitudes as the GIs are. She is also at the mercy of the South Vietnamese soldiers, who are proprietary without being protective.

The boy is Pfc. Joseph Whitaker, a rudderless kid from rural Wisconsin. Long distance, he is a good son to his elderly father, “a poor old ruin of a farmer,” but Whitaker has sizable faults too: his colossal rage, whose warning signs he is only beginning to recognize; his capricious violence, which once landed him behind bars; his binge drinking, which renders him first stupid and crude, then oblivious. He is no villain, but he is no hero either. He’s a regular Joe in his early 20s who gets drafted and sent into Lan’s world.

The ugliness that awaits him is foreshadowed on Whitaker’s last free weekend in the States, when he finds himself on the Mall in Washington, D.C. Antiwar protesters are staging a play, while American Nazis canvass likely prospects. “You watch out he don’t git you,” a young black man, standing near the Nazi recruiting sergeant, cautions Whitaker. “He don’t talk to me,” he continues. “How come is that, Sergeant?” The Nazi ignores him. “Because I’m black is the answer,” the young guy says. “Because I ain’t white.” Then the Nazi answers: “Because you’re not human.”

It’s difficult to wage war, to maim and kill people, to rape and brutalize them, without dehumanizing them first. Race is a convenient barrier to empathy; so are language and culture; likewise gender. Rabe is acutely aware of each of these striations. Part of what he’s getting at is how pervasive the lack of understanding is and how stomach-turning human behavior can be when ignorance abets barbarity or indifference.

Years ago, Rabe explained his abandonment of journal-keeping in Vietnam this way: “If you encounter an auto accident and then go home to write of it seriously, you must bring your full sensibility to bear upon all elements of that accident. To do this in Vietnam … was a task I didn’t try.” Even with his plays, he didn’t attempt that straight on: The plays are more oblique, more experimental than that, and all the more powerful for it. In “Girl by the Road at Night,” Rabe tells his story from what feels like several paces back. But stepping any closer to the scene of the horror might be too much to bear.

Collins-Hughes is a writer and editor in Massachusetts.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.