Crossing borders with ‘Sin Nombre’

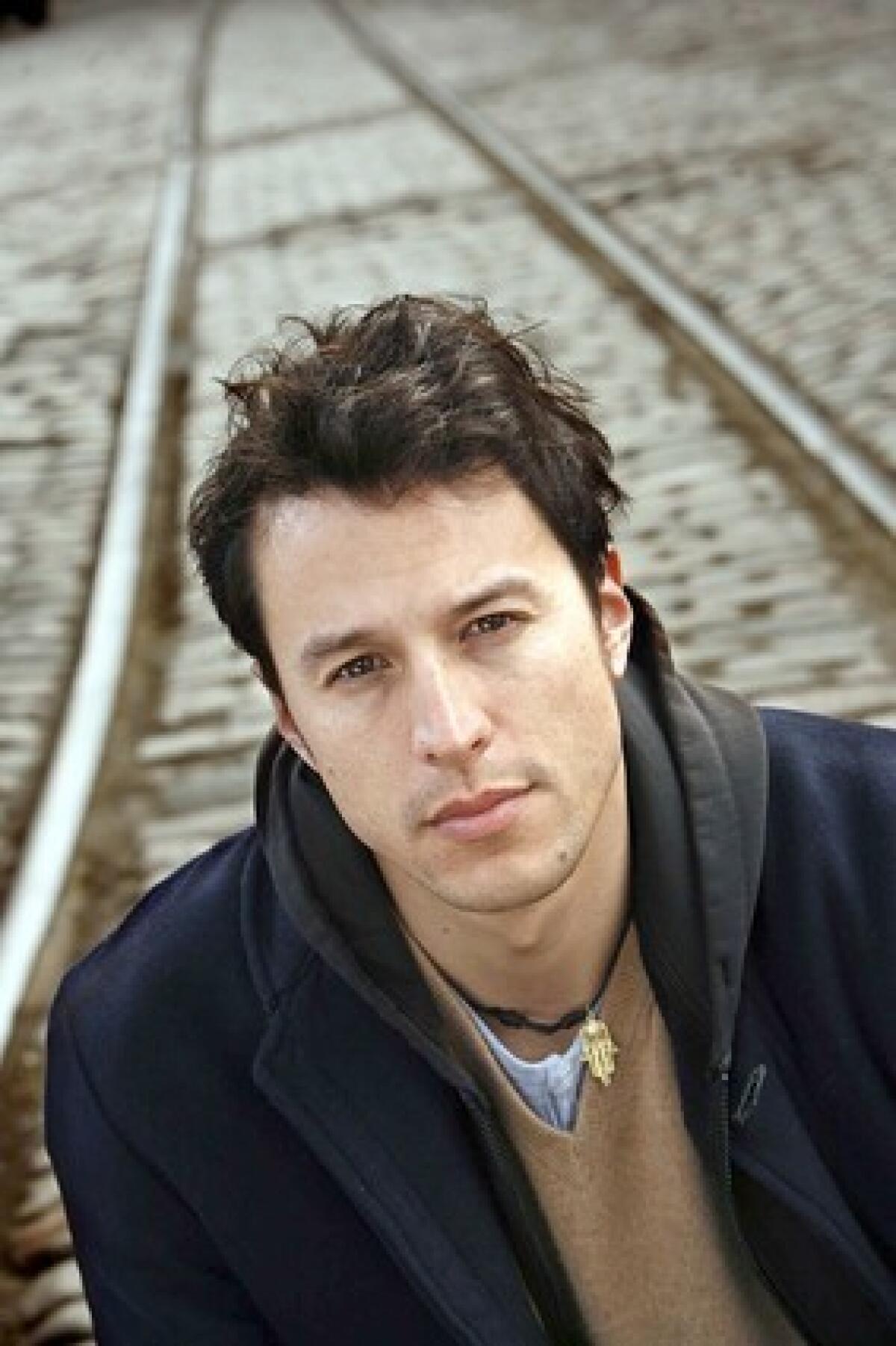

In the shattered calm of the Mexican night, sitting atop a railroad tanker car, Cary Joji Fukunaga didn’t yet know that a man was being murdered. But he’d heard the screams, gunshots and shouts in Spanish of “Bandits!” and he was bracing to make a run for it, if need be. ¶ It was summer 2005, and Fukunaga was researching the screenplay for his first feature film, “Sin Nombre,” the harrowing but uplifting saga of a Honduran girl and a Mexican ex-gang banger trying to train-hop illegally into the United States. ¶ Most aspiring auteurs probably would’ve drafted that story while safely ensconced in their Brooklyn brownstone or Santa Monica dingbat. But Fukunaga, a 31-year-old Oakland native who writes and directs movies as if he were practicing an extreme sport (he once dreamed of being a pro snowboarder) insisted on experiencing firsthand the hazards and terrors confronted by tens of thousands of economic refugees from south of the border every year. ¶ So he set off for southern Mexico to ride the rails for several weeks, braving foul weather, marauding thugs and the constant danger of falling off and being swept under the trains’ limb-severing wheels. “It felt like being a hobo in the ‘30s,” he says, hunching his slender, 6-foot-plus frame behind a metal desk in the NoHo offices of Focus Features. ¶ In the process, Fukunaga, who grew up in Northern California but has lived in New York for the last 7 1/2 years, has crafted a significant new addition to the growing corpus of movies dealing with the Latin American immigrant experience, including Gregory Nava’s “El Norte” (1983), Joshua Marston’s “Maria Full of Grace” (2004) and Patricia Riggen’s 2008 film “La Misma Luna” (“Under the Same Moon”).

Such movies, of course, have special resonance in Los Angeles, the nation’s largest Spanish-speaking metropolis, where “Sin Nombre” (which translates as “Nameless”) will open in theaters March 20. Its arrival has been preceded by a flurry of standing ovations at January’s Sundance Film Festival, where it won awards for directing and cinematography, plus critical hosannas.

“A big new talent arrives on the scene with ‘Sin nombre,’ ” proclaimed Variety’s Todd McCarthy. “Fukunaga’s enthralling feature debut takes viewers into a shadow world inhabited by many but noticed by very few.”

Indeed, the movie’s title refers to the relative anonymity of the millions of migrants, legal and illegal, who come to work in the United States.

But in “Sin Nombre,” some highly memorable names, faces and personalities are attached to those desperate travelers, particularly the main characters: Sayra, a young Tegucigalpa native hoping to unite with her absentee father’s “second family” in the New York area, and Willy, a Mexican outcast former member of the vicious, tattooed Mara Salvatrucha gang. Yoked by fate, they must make their way up Mexico’s Gulf Coast and to the United States, where Sayra has waiting relatives and Willy has a slim shot at redemption.

During his research and subsequent filming in Mexico, Fukunaga met scores of such trekkers. One time, his train stopped in the middle of nowhere in pitch blackness and robbers attacked some of the passengers. Fukunaga later learned that the robbers had killed a Guatemalan boy who’d refused to cough up his meager savings.

He also met a Honduran man who made about $3 a day in a country where milk costs $1.

“Why is he going to the United States?” Fukunaga asks rhetorically. “It’s not because he thinks our streets are paved with gold, it’s not because he thinks life’s going to be roses and flowers and hearts in the United States. It’s because that’s where he can make $13 an hour doing construction or something else and send most of it back” to his family.

Issues of immigration and identity cut deep in Fukunaga’s own complex character. “What is Cary?” is the question Hollywood speculators and puzzled journalists most often put to “Sin Nombre” producer Amy Kaufman. Who’s this guy with the gently probing gaze and Greyhound bus hair who speaks fluent French and Spanish and looks vaguely like Keanu Reeves’ brainy kid brother? A superficially laid-back dude who is, he admits, “definitely Type A underneath it all.”

The facile answer is that he’s a wandering spirit with a Japanese father, a Swedish mother, a Chicano stepdad and an Argentine stepmom. Yet, like “Sin Nombre,” a daring mash-up of love story, action thriller and starkly realistic semi-documentary, Fukunaga can’t be reduced to the sum of his parts, ethnic or otherwise.

Growing up, he shuffled from the suburbs to the country to the barrio (“Crips and Bloods, people getting shot”) to the East Bay’s hillside bourgeois enclaves.

His family, he says, always has been a “conglomeration of individual, sort of displaced people,” recombinations of relatives and step-relatives, blood kin and surrogate kin, parents and what he calls “pseudo-parents” who treated him like a son.

From a political perspective, he regards the U.S.’ decades-old immigration conundrum as a case of fairness and social justice. “We are a country of immigrants, and I don’t know why it is a tendency for humans to forget that fact,” he says.

On a personal level, his empathy for new arrivals and their stories seems related to his desire to embrace the parts of his own makeup. Tellingly, he describes the theme of “Sin Nombre” as “families in transition . . . the coming apart and re-creation of families in different forms. I grew up with families constantly in transition, different sort of iterations of it.”

He may be the harbinger of a new type of Hollywood writer-director, the “post-racial” filmmaker, who can slip easily past the stolid walls of movie genres and steer clear of the cultural sentinels who stand guard over language barriers, insisting that Americans won’t watch subtitled movies. (Uh, “ Slumdog Millionaire?” Hello?) Having lived in France, Japan and Mexico City, Fukunaga is at home in strange surroundings, at ease in his polyglot, prismatic self. “I kind of like being a chameleon in that way and trying to integrate myself in whatever place I’m at.”

The new movie’s catalyst was Fukunaga’s 2004 short film “Victoria para chino,” which screened at the 2005 Sundance Film Festival and has won more than two dozen international awards. The 13-minute movie dramatizes a May 2003 incident in which at least 74 Mexican and Central American illegal immigrants being smuggled into the U.S. in a truck were overwhelmed by overcrowding and Texas heat, causing 19 deaths.

After “Victoria” showed at Sundance, Fukunaga was asked by the Sundance Institute if he had a feature script. From a thick dossier of newspaper articles and other material, he began fashioning a screenplay from several converging story lines.

Fukunaga and Kaufman say they were moved by the Los Angeles Times’ 2002 Pulitzer Prize-winning series “Enrique’s Journey,” about a young Honduran boy’s train journey to the U.S. in search of his mother. Fukunaga also was inspired by “Days of Heaven,” Terrence Malick’s starkly poetic epic of migrant farm hands in 1916 Texas.

The contemporary migrant experience is no less lacking in poetry, or brutality. Among the hardest-luck cases are those who lack enough money to pay a coyote, or guide, to help them cross the border and must attempt the odyssey sitting on (or clinging to) a railroad car.

“Sin Nombre” captures their plight through an accumulation of details that convey the accents, slang, social customs, sights, sounds, smells and music of Mexico and Central America with a precision and authenticity rarely found in U.S.-made movies set in foreign climes. Fukunaga also visited prisons to interview gang members involved in human trafficking, and shelters serving young men and boys who’d lost arms and legs in train accidents.

Kaufman met with former Maras and agencies that work with them in Los Angeles. They shot on gang turf in Mexico, and a few gang members appear as extras.

They don’t teach you this stuff at New York University’s Graduate Film Program, where Fukunaga began churning out his first short films after earning a bachelor’s in history at UC Santa Cruz.

“Cary took the challenge of making a movie in another language, about another culture, incredibly seriously,” Kaufman says. “For him that meant that he had to be incredibly authentic, and with people on the set from Honduras checking things that you would never even notice, like the different way that people eat tacos in Honduras and in Mexico.”

In casting the film, the crucial decision was to pair Paulina Gaitan, a young but experienced Mexican actress, with Edgar Flores, a much less polished Honduran actor. Kaufman had seen Gaitan in Marco Kreuzpaintner’s “Trade” with Kevin Kline, in which she plays the victim of a Mexican sex-kidnapping traffic ring, and felt sure she’d deliver the naturalistic performance that Fukunaga wanted.

Speaking by phone in Spanish, Gaitan says it was challenging to affect a Honduran accent, but “the hardest thing was to get on the trains, because I’m afraid of heights. The first time I did it I was terrified.”

However, Gaitan had no qualms about Fukunaga, despite his relative youth. She was particularly impressed at his knowledge of immigration. “When we found that he was a U.S. director and he knew about this, we all thought, ‘Wow!’ ”

Flores turned up at an open casting call in Tegucigalpa and won the part both for his striking looks and ability to convincingly play a tough, if vulnerable, gang banger. “If you look at Edgar’s eyes, he’s not acting,” the director says. “That’s just street.”

At the beginning, Fukunaga says, “We had to really, like, discipline him, because he would just drink or he’d do whatever. He didn’t understand sort of like the opportunity that was given him. But he ended up doing an amazing job.”

Fukunaga brought an intense physicality to the set, Kaufman says. “I never saw Cary once sitting in a chair behind a monitor. When Paulina had to get in the river, and the camera guys had to get in the river, Cary got in the river. When someone had to be on top of the train in the rain, Cary was on top of the train, in the rain.”

Fukunaga seems hard-wired to take risks and make order out of chaos. No doubt his agent hopes that won’t entail death-defying acts for every film. But Fukunaga already is mapping the next journey out of his comfort zone. He’s hoping to write and film a modern musical, possibly in tandem with composer and Arcade Fire violinist Owen Pallett.

Metaphorically, if not literally, Kaufman says, “Cary has to ride the train for every movie.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.