How do you follow up a sci-fi classic without cloning it? If it’s ‘Blade Runner,’ you rewrite its DNA

The script was drafted by “Blade Runner” screenwriter Hampton Fancher. The original’s director, Ridley Scott, was key to the development process and served as executive producer. The original’s star, Harrison Ford, was in the movie. Yet director Denis Villeneuve knew his “Blade Runner 2049” would begin life at the foot of a mountain.

“Ryan Gosling and I had a lot of conversations about it,” Villeneuve says of his “2049” star. “You accept honestly that there’s a strong chance it will fail — fail in the way people will receive it — even if we do an insanely good movie, it will still be compared to a masterpiece,” says Villeneuve. “Just to relieve the pressure, I went back to making cinema for the sake of making cinema. I didn’t do it for any outside congratulations; I did it for the love of the project itself.”

A new blade runner, played by Ryan Gosling, discovers a secret that could plunge what’s left of society into chaos. The discovery leads him on a quest to find a former blade runner, played by Harrison Ford, who has been missing for 30 years.

WATCH: Video Q&A’s from this season’s hottest contenders »

In “2049,” Gosling’s K is a “replicant” (an extremely lifelike android) programmed to hunt down rogue replicants in future Los Angeles, even darker and seedier 30 years after the first movie. Taking the original’s cue, “2049” explores what defines beings as human via an android slave class treated as inanimate property, but which may be truly sentient. Unlike the 1982 film, it unravels a mystery through a character we know from the start is a replicant. Though he must uncover the truth, it’s not clear K is equipped to deal with what he might learn.

Villeneuve says, “The replicants are designed for very specific purposes. The have strong skills, high intelligence. Their weakness is a vulnerability from an emotional point of view. They don’t have the baggage to be able to digest the new events occurring around them, specifically dealing with intimacy. That makes them fragile in some way.

Because K is essentially a faceless cog in an unfeeling, dystopian machine, the resemblance of his name to Franz Kafka’s “The Trial” protagonist seems fitting. Villeneuve refers to the “big literary background” of Fancher and co-writer David Green, saying “there are no accidents” in their script.

Like its replicants, the sequel is a construct grown from provided materials, but finds its own, unique life. To gestate it, Villeneuve first had to inhale the existing draft and exhale it with his own DNA mixed in; he was afraid the ongoing, complex editing process of his previous film, “Arrival,” might hinder that effort.

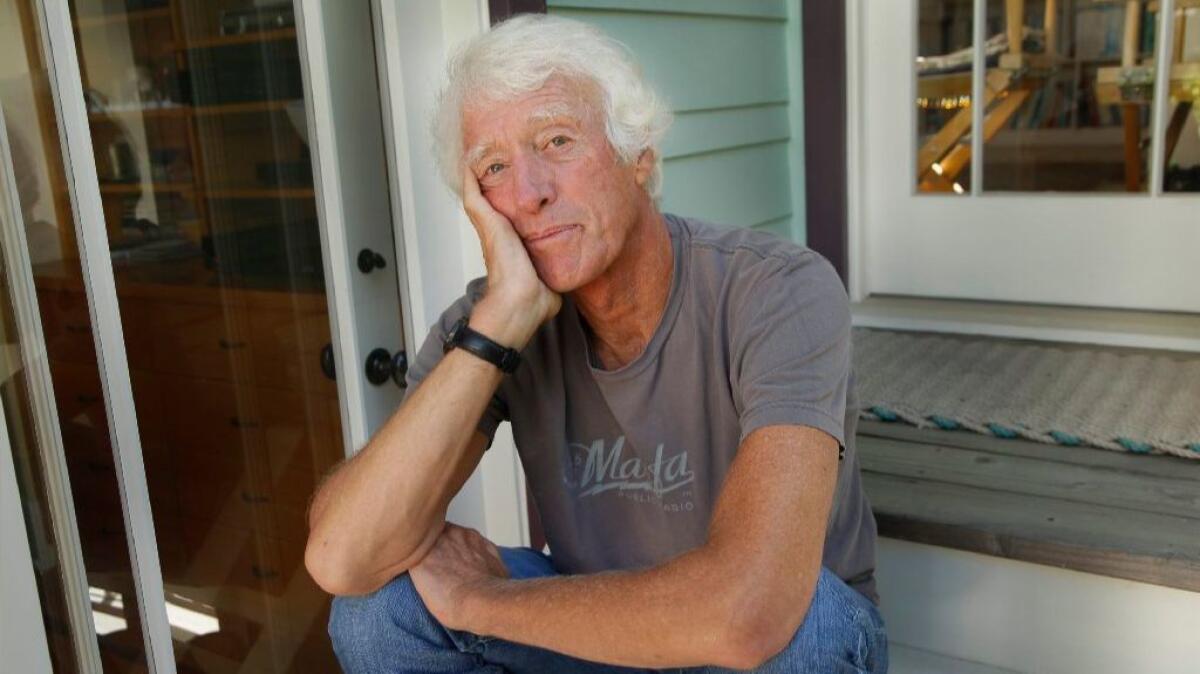

“I needed someone to help start the process” of “Blade Runner,” he says. “Instead of dreaming alone in my room, I needed someone to bounce ideas off of, someone that I deeply trust. Roger said yes right away.”

That would be Roger Deakins, the master cinematographer (and 13-time Oscar nominee) with whom Villeneuve had collaborated on “Prisoners” and “Sicario.” While most filmmakers would list directors of photography among their closest partners, it’s unusual for one to be involved at such a formative stage.

“He came to the hotel room in Montreal with me. We sat for hours, for days, for weeks with two storyboard artists. We drew all the movie. When you storyboard the movie, you rewrite the script in some ways.

“And we brainstormed to find the rules of this world, the geopolitics, the light, the atmosphere. Everything was born in those sessions of work.

“The production designer, Dennis Gassner, joined us and we did the bible of the movie. The main ideas were born there, that, to my great satisfaction, I see on the screen today.”

Villeneuve’s film is texturally rich, from its smog-darkened L.A. noir to its future-industrial wasteland; from its post-apocalyptic Vegas to its zen-minimalist billionaire’s lair. It’s also contextually rich, as geopolitical circumstances such as how climate change had caused sea-level rise, triggering local floods of both refugees and water (hence the “Sepulveda Seawall”), were seeded in those early laboratory sessions.

“We took a lot of liberties visually, but I wanted the sound design to be very close to the first movie. The spirit of that atmosphere, expressionist,” says the director. “A lot of time you’d hear sounds in the first movie, you’d have no idea where they were coming from. They were textures. Half music, half sound design. We kept that spirit.”

Considering just how much his collaborators shaped his idiosyncratic response to Scott’s 1982 classic, Villeneuve smiles broadly.

“It’s what I love about filmmaking. If I wanted to be alone, I’d do ice sculpture in my basement.”

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.