Year in Review: In 2014, hip hop takes a potent stand

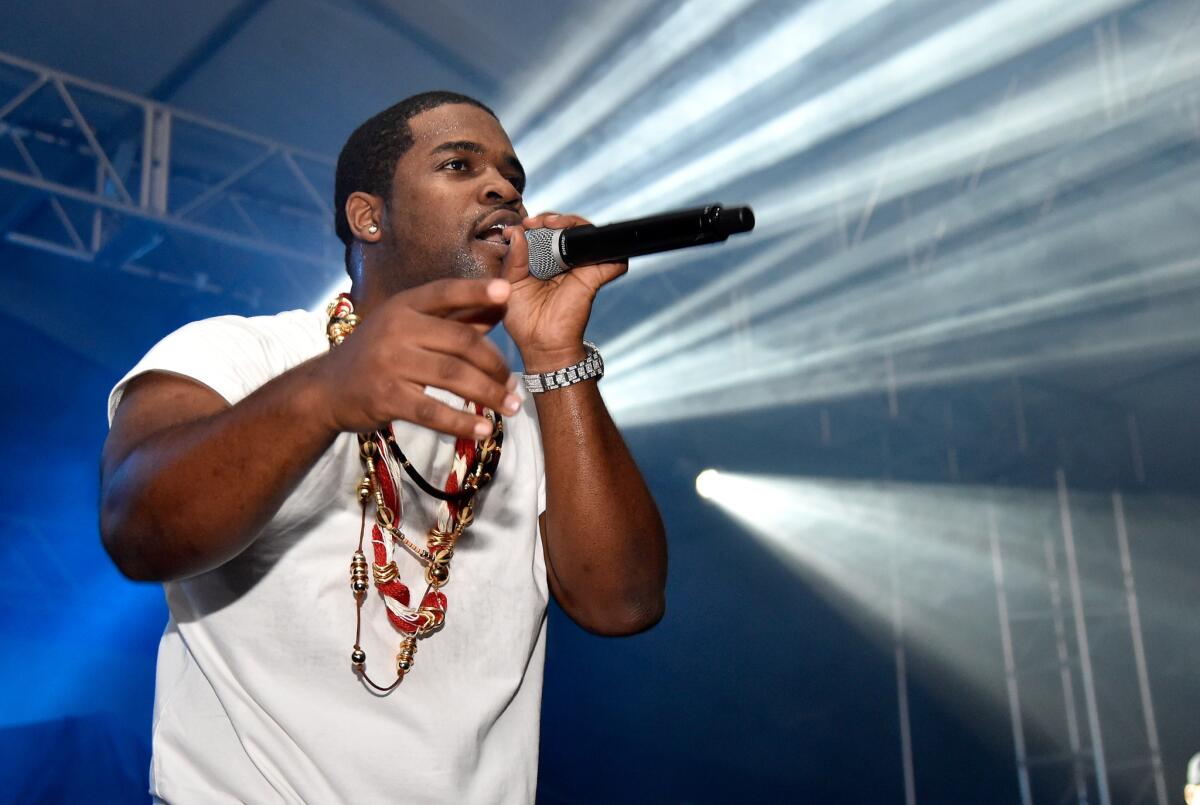

There’s a line in New York rapper ASAP Ferg’s syrupy new track “Talk It,” a musical response to the death of Michael Brown and the subsequent riots in Ferguson, Mo., that underscored the calcified nature of relations between black communities and the police across America in 2014.

The verse, dotted with cusses, is the last track on his new mixtape, “Ferg Forever.” Ferg recalls nights riding with his uncle, “NWA blastin’, we screamin’, ‘… tha Police,’” he raps, referring to the harsh gangsta rap anthem released by the Compton group in 1989. That song, issued amid gang violence in the years before anger exploded during the 1992 Los Angeles riots over four police officers’ acquittal in the Rodney King beating, is an incendiary artifact — and stills serves as crucial evidence two decades later. “‘Cause they don’t give two … about me,” continues Ferg. “I mean when I say Ferguson they talk about me.”

Ferg was only 2 months old when NWA’s barbed oath was released, but his and other rappers’ response to the deaths of Michael Brown in Ferguson and Eric Garner in Staten Island, N.Y., at the hands of police underscored that hip hop in 2014 remained true to its birthright as a political art form. Dozens of tracks popped up in the weeks after their deaths, each a snapshot op-ed from voices whose medium brought into the present a long history of quick-react musical protests. If marquee names such as Kanye West, Drake, Kendrick Lamar and Nicki Minaj declined to issue musical responses — and Jay Z employed another asset by financing the “I Can’t Breathe” T-shirts that NBA players have been wearing during warmups — the underground was rife.

With YouTube and Soundcloud offering immediate distribution — and commercial radio ignoring them in favor of depoliticized music — the songs paid witness. Using a laptop and headphones to build beats, rappers and producers ripped the system like folkies and funk bands did during the civil rights movement decades earlier. The best were nuanced reactions that took on the cops and the looters or contained an urgency that echoed the politicized work of the Last Poets and Gil Scot Heron, of Grandmaster Flash & the Furious Five’s “The Message,” Public Enemy’s “Fight the Power” and collected work of Rage Against the Machine.

Big names like T.I. (“The New National Anthem”), the Game (“Don’t Shoot,” featuring Rick Ross, Diddy, Wale and others) and underground artists including Clipping, Run the Jewels, Tef Poe and Gage channeled outrage into art. Soul superstar D’Angelo’s long-gestating new album, “Black Messiah,” credited in its liner notes “people rising up in Ferguson and in Egypt and in Occupy Wall Street and in every place where a community has had enough and decides to make change happen.”

Years in the making, the album’s unanticipated arrival on Monday seemed like a series of boldfaced exclamation points to end the year. Best, unlike the underground tracks that mostly preached to the converted, “Black Messiah” will likely debut at No. 1 on the album charts.

Smaller works were just as potent. New Orleans veteran Turk’s “Hands Up” delivered forlorn hooks that echoed Billie Holiday’s tone during “Strange Fruit.” Others, like K.O.B.’s horrifying “Break They Laws!!!” advocated forming a new country with cuss-heavy — and anti-Semitic — rage. Though it felt like unedited scribbles on an alley wall, it illustrated the range of outrage.

Just as a century earlier in St. Louis the murder of Billy Lyons by one Lee “Stack Lee” Shelton spawned a classic song, “Stack-o-Lee,” which recounted the slaying (over a Stetson hat) and the shooter’s run from the law, the new tracks turned violent reality into music. A few miles from the long-gone riverfront bar where that happened, St. Louis rapper Tef Poe dropped “War Cry,” which took on Michael Brown and then-Police Officer Darren Wilson.

A musical shot aimed at Missouri Gov. Jay Nixon’s response to the death, the track is a blistering four-minute verbal op-ed that names names, calling out the city’s politicians and policemen. Whether one agrees with his take or not — “Darren Wilson got rich from murdering Mike Brown” — Tef Poe’s of-the-moment energy, backed by percussive, wobbly beats produced by DJ Smitty, sounds uncontainable, especially when he raps, “Ferguson is Barack Obama’s Katrina.”

Chicago lyricist J. Cole’s remarkable recently televised performance of “Be Free” nearly brought David Letterman to tears. A rich, emotional reaction issued in the summer, the minor key song opens with Cole sounded exasperated, declaring that “ain’t no drink out there that can numb my soul.”

The singer and rapper, one of a few nonlocal artists to travel to Ferguson in the days after the unrest, moves into a chorus that could have been written by countless black Americans at any point in the past 250 years: “All we want to do is take the chains off/ All we want to do is break the chains off/ All we want to do is be free.”

Phoenix artist Trap House sounded nearly defeated in “Imagine” as he listed generations of violence. “Been here and died before/ Been hung from a tree, set on fire before,” he rhymes before quoting Martin Luther King Jr. and connecting past and present: “The black men never see college/ Crack is the new form of cotton.”

That the event when viewed through the lens of hip hop offered consensus opinion that blamed the police shouldn’t be surprising. But the dearth of works that defended the officers is notable. Amid the dozens if not hundreds of works dedicated to Brown and Garner, I could find only one clip siding with Wilson. It’s not the work of white power punk band Brutal Attack praising the police action, or a racist country band releasing music on Rebel Records. Rather, it shows a shirtless white man in bed singing a cappella. He raises his fist in victory as he sings, “Darren Wilson never indicted/ Mike Brown just a stupid thug.”

Compare that to the reaction of Run the Jewels’ Killer Mike, who performed in St. Louis the night that the grand jury decided not to indict Wilson in Brown’s killing in August. In a memorable pre-show speech that went viral, the rapper got personal as he told of watching prosecutor Robert McCulloch’s televised announcement. “I have a 20-year-old son and I have a 12-year-old son, and I’m so afraid for them,” he said, barely holding back tears.

He raged about power, about race, poverty and control. Then he and his collaborator El-P, who is white, moved into the set’s opening song as a frenzied crowd bounced and hollered: “These streets is full with the wolves that starve for the week — so they’re after the weak,” rapped Killer Mike. “In a land full of lambs I am/ And I’ll be damned if I don’t show my teeth.”

It bears repeated listens — preferably at full volume and with focused attention.

Twitter: @LilEdit

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.