Full Coverage: Satire, art and culture

The massacre at Paris satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo raised a host of questions about terrorism, and social and security policy. It also thrust the art of cartooning — and satire more generally — into the headlines and cross hairs.

Below, Times writers and critics look at the cultural background and implications from a variety of angles.

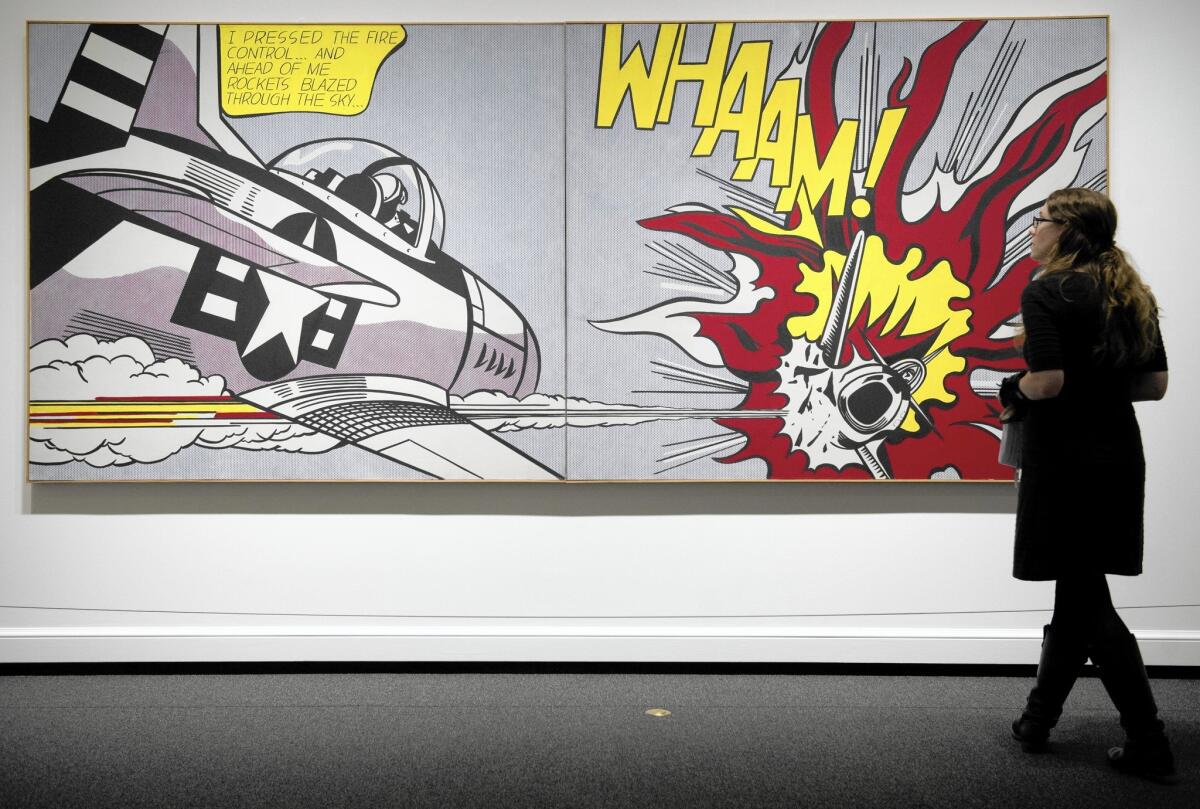

Roy Lichtenstein became one of the most prominent artists embracing the spirit of comics. Among his most recognizable works is "Whaam!" (1963). (Saul Loeb / AFP/Getty Images)

No joke here

Cartoons, at satire's forefront, press against hard lines. That impulse has opened doors. And made enemies. The Times' art critic, Christopher Knight, offers his take.

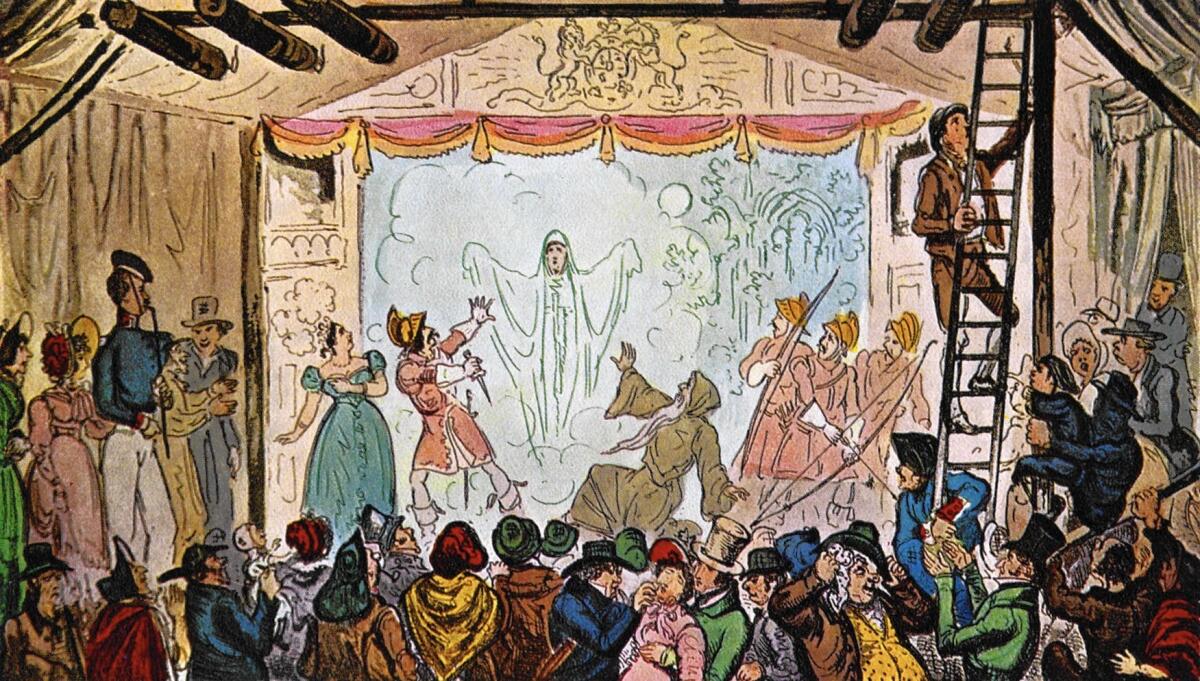

Bartholomew Fair as seen from the inside during a performance to a large crowd. Engraving by R Cruikshank, 19th century. (Culture Club / Getty Images)

Point made with zeal

Unlike the Charlie Hebdo tragedy, the fight between artist and zealot in Ben Jonson's "Bartholomew Fair" ends in conversion and dinner. Gustavo Turner revisits.

Syrian artist Ali Farzat regularly took on corruption and the military in his political cartoons. Farzat had his hands broken after creating a political cartoon that showed Syrian leader Bashar Assad in a bad light in 2011. (Yasser Al-Zayyat / AFP/Getty Images)

A global custom

Contrary to what some may think, the ridiculing of leaders and pretensions through satire has a long history in every culture. The Times' High & Low blogger, Carolina A. Miranda, explores.

Margaret Cho, center, joined Tina Fey, left, and Amy Poehler at the Golden Globes to satirize the North Korean regime. The act was viewed as racist by some. (Paul Drinkwater /NBC)

The limits of free speech

Charlie Hedbo and American liberalism sprung from the same sort of protests, but in the U.S., acceptance trumps mockery. Times TV critic Mary McNamara dives in.

As Joseph Heller wrote in "Catch 22": "It was almost no trick at all to turn vice into virtue ... sadism into justice ... It merely required no character." (Iris Schneider / Los Angeles Times)

A fading tool

As satire withers, the question is: Has America turned into a spoof itself? The Times' book critic, David Ulin, takes note.

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.