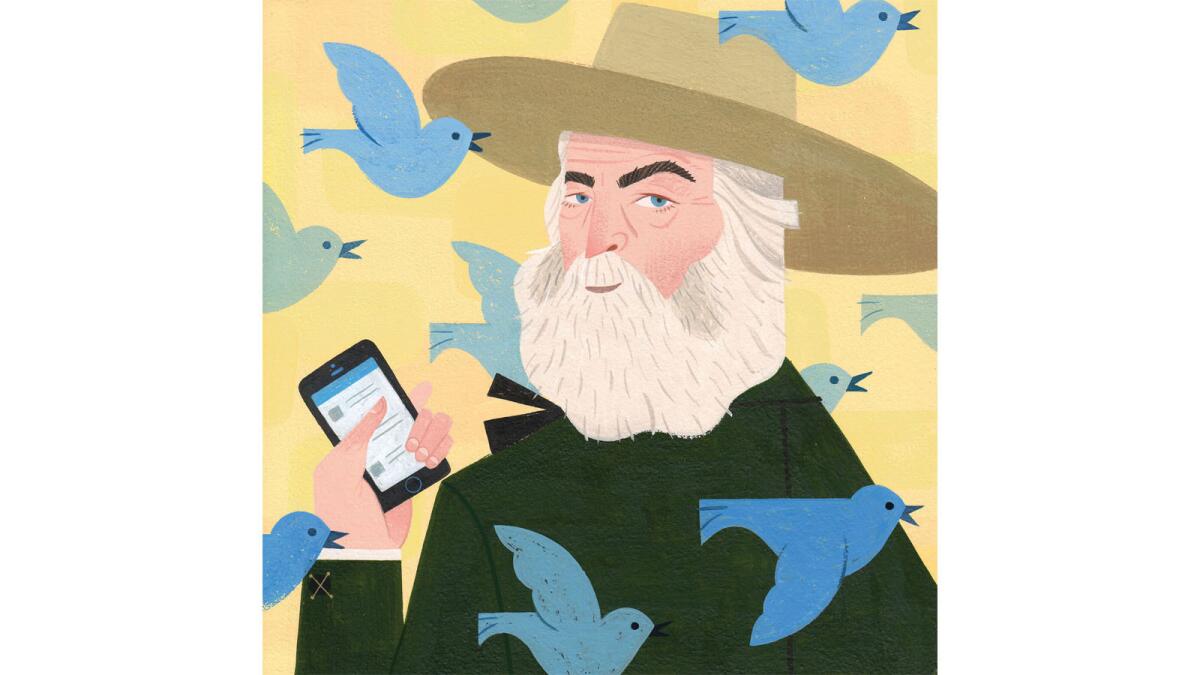

Dealing with social media buzz: Walt Whitman might understand

My smartphone glows with excitement. I have a new Twitter follower. His name is Francesco. He describes himself as “Reputation Management. Music, Fashion, Art, TV, Film.” His address is “In a State of Self-Indulgence.” How cool is that? He has 15.2K followers.

I have 823, down from 826 a day earlier. Where do the lost ones go? I feel like a preacher with an empty middle pew. I need to expand my Twitter flock. My followers and those whom I follow say a lot about me — passions, desires, interests and whims I never knew existed. Why, for instance, am I following Thunder Thigh Gap, “City councilwoman for Pawnee, Indiana”?

Since I moved to California after years as a foreign correspondent, my email traffic and social media friends/followers have changed. Where once I received emails and tweets from rebels and revolutionaries across the Middle East, or from Human Rights Watch condemning bloodshed in Egypt, I am now fielding missives and alerts from plastic surgeons, publicists, yoga studios, “Super Troopers 2” and bloggers breathless over the latest Kardashian misadventure.

It’s dizzying. Relentless. So much information flowing across screens; so little of it inspiring. How does one respond to news about celebrities, selfies and sock monkeys? And how would my new Twitter follower Lonesome Liz — “Americana/Blues artist & creator of Voodoobilly, Conjure Woman and reader/medium” — get along with Matar Matar, an activist in the repressive kingdom of Bahrain? Such are questions for the age.

My inboxes and accounts are universes containing multitudes, holding my past, shaping my present, careening me into a future of infinite alliances. I can choose them, of course, pick my tribe. I can delineate and segregate. I picked Francesco, after all, who after I followed him dropped “Reputation Management” from his moniker. But there are so many voices out there, buzzing to be heard.

Each one desperate to be clicked on or friended. Chosen. Understood. Our technology enables what our narcissism craves. Although he predated the World Wide Web by about a century, Walt Whitman, had he a Facebook page, might have posted his poem “Among the Multitude.”

“Among the men and women the multitude,

I perceive one picking me out by secret and divine signs,

Acknowledging none else, not parent, wife, husband, brother, child, any nearer than I am,

Some are baffled, but that one is not — that one knows me.

Ah lover and perfect equal,

I meant that you should discover me so by faint indirections,

And I when I meet you mean to discover you by the like in you.”

Social media accounts demand thousands of “likes” and “yous.” They spur trends, create and drive traffic and occasionally illuminate. Amid the din and flash, we look for sages who in 140 characters can crystallize important topics, such as the speed at which Iranian nuclear centrifuges spin and the meaning behind Justin Bieber’s newest tattoos. We retweet them; we favorite them. We propel them toward fresh frontiers.

We check our smartphones — constantly — for glimmers of acknowledgment. The Center for Internet and Technology Addiction says, “Smartphones are the world’s smallest slot machines.” The organization cautions that “the Internet operates with a high degree of unpredictability and novelty.... Whether it’s gaming, sexual content, e-mail, texting, facebook, shopping or general information surfing, they all support unpredictable and variable reward structures.”

This naturally led me to Google. I typed in “social media overload.” A website for a new book, which happens to be titled “Social Media Overload,” was the first thing that popped up. “You don’t have to be on Twitter! You shouldn’t be on any social media platform without a clear reason for why you’re doing it and ways to measure results,” it advised. “If you’re not generating results from a particular social media site, then it’s just a hobby. You don’t need any more hobbies.”

I straddle many voices. I wonder if I should untangle myself from some. The tweeter in Lebanon, the blogger in Sudan, the activist emailer from Saudi Arabia, the journalist in Yemen who watches the bombs fall on an ancient city. They are not what I do anymore. I write different stories now. Movies. Art.

I will hang on to those distant voices. They’ll keep me honest and focused on the true power and benefit of social media. Two nights before the Egyptian revolution erupted in 2011, I sat in a cafe sipping juice with Ahmed Maher, a leader of April 6 Youth Movement, which organized protesters through Twitter and other social media. Maher didn’t want to predict if the street marches would be strong enough to bring down President Hosni Mubarak. He kept checking his smartphone, scanning tweets, sending out texts.

Mubarak fell. But a new generation of military men, with even less tolerance for dissidents, took his place. Maher is in jail. His Twitter account, though, is alive and thriving. He has 206,000 followers. Imagine that — a man walled off from the world has a platform for justice that can’t be quieted.

Which brings us back to Whitman:

“I celebrate myself, and sing myself,

And what I assume you shall assume,

For every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.