Will films like ‘Furious 7’ ever get the Academy Awards’ respect?

Charlton Heston in costume and riding a horsedrawn chariot in a publicity still for the 1959 film “Ben-Hur.”

It was a bold and cocky bit of theater last spring when Vin Diesel proclaimed that his film “Furious 7,” which went on to gross more than $1.5 billion worldwide, was a blockbuster worthy of an Oscar if, of course, the Academy Awards wanted to remain relevant for a younger, culturally diverse generation.

It is no surprise that despite Diesel’s gleam and swagger, “Furious 7” was not nominated this year for an Academy Award for best picture. The film may have drawn strong reviews and reached one of the biggest audiences in Hollywood history, but in the eyes of the voting members of the film academy, it lacked a certain je ne sais quoi: It was big, sleek and fun but not the kind of sophisticated, socially relevant (and many would say white) movie that’s been honored — especially in the last 20 years.

If the Academy Awards were “Downton Abbey,” then “Furious 7” would have a tidy room in the servants quarters. The upstairs would belong to nominated films such as “Bridge of Spies,” a Cold War thriller set in a divided Berlin that has grossed $160 million worldwide, and “Brooklyn,” a 1950s tale of an Irish immigrant torn between her homeland and New York that has earned nearly $28 million domestically. They are regal and pretty, conveying the style and substance the academy likes to invite for dinner.

SIGN UP for the free Gold Standard newsletter >>

“Orson Welles once said that what governs the Academy Awards aren’t always the best films but what Hollywood [executives] make to impress one another,” said Joseph McBride, a film historian and cinema professor at San Francisco State University. “It’s really an industry problem, and it’s time for people to examine their consciences for what films they green-light. The scale of films is too narrow.”

What constitutes an Oscar-worthy film is likely to be redefined, and some in the industry wonder how race may factor into academy voting. The pressure put on the academy by the #OscarsSoWhite movement seems certain to affect the institution’s nominating calculus, notably after black actors such as Michael B. Jordan and mainstream racially diverse movies, including “Creed” and “Straight Outta Compton,” were passed over this year.

The aesthetics of an Oscar movie have changed over the decades, from mainstream pictures to smaller art-house fare. But these days, the culturally diverse casts in “Furious 7” and other franchise films more closely reflect society, a prospect that may eventually lead the academy into taking Diesel’s comments to heart. (In fact, the academy recently changed its membership rules in hopes of doubling the number of minority and female members.)

A similar recalibration of academy dynamics occurred when a new wave of filmmakers emerged out of the political upheaval of the 1960s, and again decades later, when the bluster and marketing genius of Harvey Weinstein set a new tone for what an Academy Award winner should look like with films such as “Shakespeare in Love.”

But Hollywood, like America, is more complicated on matters of race and taste than the often facile debate over this year’s academy nominations of only white actors. The overwhelmingly white academy has been accused of racial insensitivity for more than a generation. The latest clamor arises in an era of YouTube videos showing police brutality against blacks, changing cultural demographics, new debates over affirmative action, a backlash against political correctness and a nation still unsettled over how to move beyond the racial sins of its past.

It is cinematic sweep in real time, and Hollywood, often slow to capture the world around it, may have to adjust to be more relevant to a domestic market, even as blockbusters fuel the growth of its international box office.

“This is the what-do-we-do-about-it? phase,” Barbara Boyle, an associate dean at UCLA’s film school and co-founder of Sovereign Pictures, which distributed and financed such Oscar-winning movies as “Cinema Paradiso” and “My Left Foot,” said of Hollywood’s lack of diversity. “The film industry reflects what the country is. Unfortunately, there’s a gap. But there won’t be any business if no one sees what we’re making.”

In the view of the industry and the academy, blockbusters blow things up, make money and glow with cheeky effervescence. They rarely win big awards. But even the academy can break stride: Among the nominees for best picture this year is “Mad Max: Fury Road,” director George Miller’s hellish, gonzo trip across a parched dystopia. (To be sure, some blockbuster films have won in more recent years, including “Titanic” and “The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King.”) Yet the academy this year didn’t give a best picture nod to “Star Wars: The Force Awakens,” on pace to be the biggest money-maker in history, whose cast of culturally mixed actors was more in sync with today’s film audiences than prequels whose notion of diversity was Jar Jar Binks.

It feels counter-intuitive that an industry so consumed with money and box office receipts often considers neither when selecting what it holds up as its finest work. It is the cinematic equivalent of Jay Gatsby, the epitome of wealth and the American dream, who stages his reunion with Daisy Buchanan, the ill-fated love of his life, in a small cottage rather than amid the glitter of his mansion. Some things, the academy seems to be saying, money cannot buy.

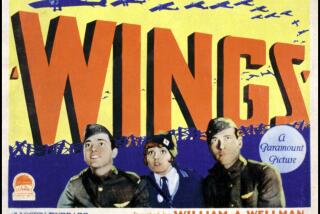

But the big-budget movie — and studio ambitions of $1 billion-plus in ticket sales — is the industry’s bellwether. Earlier blockbusters such as “Gone With the Wind” (1939) and “Ben-Hur” (1959) were considered prestige movies and won troves of Academy Awards. But later incarnations, from “Superman” (1978) to the torqued-up Marvel superhero franchise films, were driven by special effects and built more for diversion than reflection — and were by and large ignored at the Oscars. They exemplified America’s fascination with futuristic gizmos, comic books, other worlds and escapism and were built to appeal to the widest worldwide audience possible.

“There’ll always be blockbusters, and possibly with more diverse casts,” said Robert Greenwald, an independent filmmaker and founder of Brave New Films. “The blockbuster today is driven by economic decisions, games and merchandising. The so-called small art-house films will be where the greater risk-taking will happen, and those are the ones that win awards. It’s tough to make a film that is adventurous.”

Adventurous zeal swept Hollywood with indelible images in the late 1960s and the ‘70s, when filmmakers such as Warren Beatty, Mike Nichols, John Schlesinger and Peter Bogdanovich re-imagined cinema with jolting realism that deciphered a culture shaped by civil-rights protests, drugs, the Vietnam War, rock ‘n’ roll and sexual freedom. “Midnight Cowboy,” “The Graduate,” “Bonnie and Clyde” and “The Last Picture Show” influenced filmmakers around the world and reinvented the essence of Oscar-worthy movies.

In his book about that era, “Easy Riders Raging Bulls,” Peter Biskind quoted Steven Spielberg about the transformation of the industry: “The ‘70s was the first time a kind of age restriction was lifted, and young people were allowed to come rushing in with all of their naiveté and their wisdom and all of the privileges of youth. It’s was just an avalanche of brave new ideas, which is why the ‘70s was such a watershed.”

Oscars 2016: Full Coverage | Complete list | Snubs, surprises and reactions | Top nominee photos | #OscarsSoWhite, again

Weinstein changed the rubric again in the early 1990s. Producing eclectic films, notably polished period pieces, Weinstein marshaled blitzkrieg marketing campaigns that undermined competing movies and spent lavishly on advertising, parties, press junkets and minions. With an irascible showman’s perseverance, he was at once reviled by some (privately, of course) and praised for his passion for and knowledge of movies.

Films backed by Weinstein and his brother, Bob, have received 341 Oscar nominations and won 81 Academy Awards, including best picture prizes for “The English Patient,” “Shakespeare in Love,” “The King’s Speech” and the mostly silent black-and-white movie “The Artist.” The Weinstein Co. didn’t fare as well this year; his top contenders — Todd Haynes’ “Carol” and Quentin Tarantino’s “The Hateful Eight” — received numerous nods but were left off the best picture nomination list.

“Weinstein is like one of those old-fashioned executives who ran the studios in the Golden Age. They were crass and vulgar, but they loved movies. He loves movies,” said film historian McBride, who has written biographies on Frank Capra and other directors. “He’s the master of manipulation, and he’s pretty brazen about that.”

One of Weinstein’s breakthrough films was “My Left Foot,” the tale of a man with cerebral palsy, starring Daniel Day-Lewis, who won an Oscar for it. The 1989 movie was also nominated for best picture. “I see it starting with ‘My Left Foot,’” said Boyle. “It was a little Irish film, but it really represented a moment for me when independent films came on the radar as academy-attention kind of films.”

The movies that arise from the academy’s latest landmark moment may increasingly include performances and stories by and about blacks, Latinos and other minorities. Some suggest that by increasing the number of African Americans in the academy, movies such as “Straight Outta Compton” will have better odds for an Oscar. That assumption doesn’t reflect a more complex reality.

Two years ago, for example, “12 Years a Slave” was named best picture, and three black actors received Oscar nominations: Barkhad Abdi for “Captain Phillips” and Chiwetel Ejiofor and Lupita Nyong’o (who won for supporting actress) for “12 Years a Slave.”

Race, as black and white academy members have noted, should not be a prism for artistic merit. But with an incessant concentration on profits and an air of hubris, Hollywood has been slow to mirror the vast audiences beyond Beverly Hills and the canyons.

“I’ve seen the first African American president of the United States, and I may see the first woman president,” said Boyle, who joined the academy in 1977. “But there’s no doubt in anybody’s mind that the number of women and minorities in film and television is dismal when compared to the population.”

That may change if Hollywood embraces a more nuanced sense of the times and moves beyond the narrow definition of an “awards film,” so movies such as “Creed” can someday be in the Oscar conversation.

Twitter:@JeffreyLAT

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.