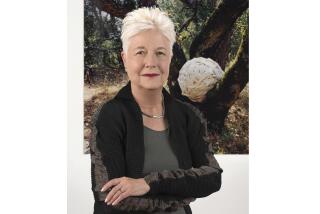

Jean Rouverol, blacklisted screenwriter, dead at 100

Jean Rouverol, who died Friday at age 100, was well acquainted with how the blacklist era divided Hollywood.

An actress-turned-screenwriter, she and her screenwriter husband, Hugo Butler, were targeted by the House Un-American Activities Committee and went into exile with their children for 13 years in Mexico.

After their return to the U.S., she became a writer on the soap operas “Guiding Light” and “As the World Turns.”

According to the Horn and Thomes Funeral Home in Pawling, N.Y., she died of unknown causes in Wingdale, N.Y.

Born in St. Louis on July 8, 1916, Rouverol was the daughter of Joseph Rouverol and Aurania Ellerbeck Rouverol, who, like her daughter, was an actress turned writer — though the elder Rouverol’s first medium was the theater. For the 1928 play ‘Skidding,” she created the Andy Hardy character at the center of the MGM films and went on to write the 1931 Joan Crawford film “Dance, Fools, Dance.”

Following in her mother’s path, young Rouverol, started acting. The summer she turned 18, on break from Stanford, she was pulled from a Max Reinhardt production of “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” at the Hollywood Bowl (with Mickey Rooney as Puck), to star in the 1934 Paramount movie “It’s a Gift” as W.C. Fields’ daughter.

“I remember being so insulted,” Rouverol said in a Writers Guild Foundation interview recorded in 2000. “My feeling was they took me out of a Shakespeare play to make me act with this drunken vaudevillian?! And of course, that’s now a classic! Very few people remember Max Reinhardt and his plays.” (Reinhardt, who established the world-famous Salzburg Festival, went on to co-direct the 1935 film production of “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” with James Cagney, Dick Powell, Olivia de Havilland in the role Rouverol was going to play at the Hollywood Bowl, and Rooney still as Puck.)

“I considered movies a kind of vulgar variant,” on the theater, Rouverol said in the Writers Guild interview.

Even so, Rouverol acted in another dozen films, including 1936’s “The Leavenworth Case” and “Fatal Lady,” 1937’s “Stage Door” with Katharine Hepburn and Ginger Rogers, plus 1938’s “Annabel Takes a Tour” with Lucille Ball and “Western Jamboree” with Gene Autry. Her most recent role was in a short titled “Finding Jean Lewis” in 2009.

Except for that last role, she had stopped acting in the movies by 1940 after starting a family with Butler. She continued to perform on radio during the ’40s, including the role of Betty Carter on the NBC radio serial “One Man’s Family.”

While Butler served in World War II, Rouverol wrote her first novella and sold it to McCall’s magazine in 1945. By 1950, her first screenplay had been made into a movie, “So Young, So Bad,” about a girls reform school, starring Paul Henreid and featuring the film debut of Rita Moreno as a suicidal teen.

But Rouverol’s screenwriting career was halted after it was discovered that in 1943, when the U.S. was still allied with the Soviet Union during World War II, she and Butler had joined the American Communist Party.

In 1951, the House Un-American Activities Committee attempted to subpoena the couple. Rouverol and Butler chose to self-exile with their four children in Mexico rather than face a possible prison sentence as endured by some of their friends who were part of the so-called Hollywood Ten.

Rouverol and Butler were labeled as “subversives and dangerous revolutionaries” by the government and didn’t return permanently to the U.S. until 1964. Acclaimed screenwriter Dalton Trumbo came to live with the couple in Mexico after he was released from an 11-month sentence in a federal penitentiary for contempt of Congress when he refused to give information to the committee.

While in exile, Rouverol had two more children and continued to write screenplays, short stories and magazine articles to earn money. Three screenplays she co-wrote with Butler were accepted for filming by Hollywood studios, only because agent Ingo Preminger, brother of director Otto Preminger, arranged for others from the Writers Guild of America to put their names on the scripts.

The couple settled in California upon their return from Mexico. The two continued to collaborate on scripts, and Rouverol wrote the book “Harriet Beecher Stowe: Woman Crusader.”

Butler died in 1968. And Rouverol returned to writing in the 1970s, penning an episode of “Little House on the Prairie” and being hired as co-head writer for the soap opera “Guiding Light.” The latter earned her two Daytime Emmy nominations and a Writers Guild award. Rouverol left the show in 1976 when she was 60.

In 1984, she penned “Writing for the Soaps” and taught at USC and UCLA Extension. Three years later, she received the Writers Guild’s Morgan Cox Award.

In 2000, at age 84, she published “Refugees From Hollywood: A Journal of the Blacklist Years” about her family’s life in exile, in which she spoke about the blacklisted artists’ refusal to plead the 5th Amendment against self-incrimination.

“The 5th Amendment implied guilt, so nobody took the 5th initially,” she recalled. “It implied that they were ashamed of their political activities. . . . They all thought that standing on the 1st Amendment [instead] would keep them out of jail. It didn’t. The Supreme Court refused to hear it.”

Rouverol moved to Pawling in 2005, where she lived with her partner Clifford Carpenter, another former blacklisted artist. He died in 2014.

Rouverol is survived by her son Michael Butler; five daughters, Susan Butler, Becky Butler, Mary Butler, Emily McCoy and Deborah Spiegelman; eight grandchildren and five great-grandchildren.

SIGN UP for the free Classic Hollywood newsletter >>

Follow me on Twitter (@TrevellAnderson) or email me: trevell.anderson@latimes.com.

ALSO

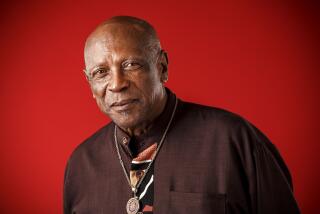

Disproving the Hollywood myth that ‘black films don’t travel’

With ‘Love Jones,’ black love took center stage: An oral history

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.