‘The Perfection’ twist ending explained by director Richard Shepard

Warning: The following article contains major plot spoilers for the Netflix thriller “The Perfection” including the twist ending.

When director Richard Shepard wrote the psychological revenge thriller “The Perfection” with Eric C. Charmelo and Nicole Snyder, he didn’t realize its themes of sexual abuse and assault would erupt on a national scale months later after Harvey Weinstein’s public fall from grace.

“It was very strange,” said Shepard, who’d been inspired to tell the story after watching the Netflix docuseries “The Keepers,” about the murder of a nun and the church’s subsequent cover-up.

“It really stuck with me and has always driven me mad not only that people are abused but that it’s covered up,” he said. “That drives me nuts. And so I wanted to get that into this genre movie, but to do it in a way that didn’t feel exploitative.”

That desire dovetailed with the increasing trend of genre movies that either tackle or acknowledge serious issues. “Listen, we’re seeing a lot of bad things in the world,” Shepard added. “We’re living in a really, really tough moment, and a lot of people are sick of it and want the bad things to stop. Revenge has always been in movies; it’s happening now in a sort of ‘elevated horror’ style.”

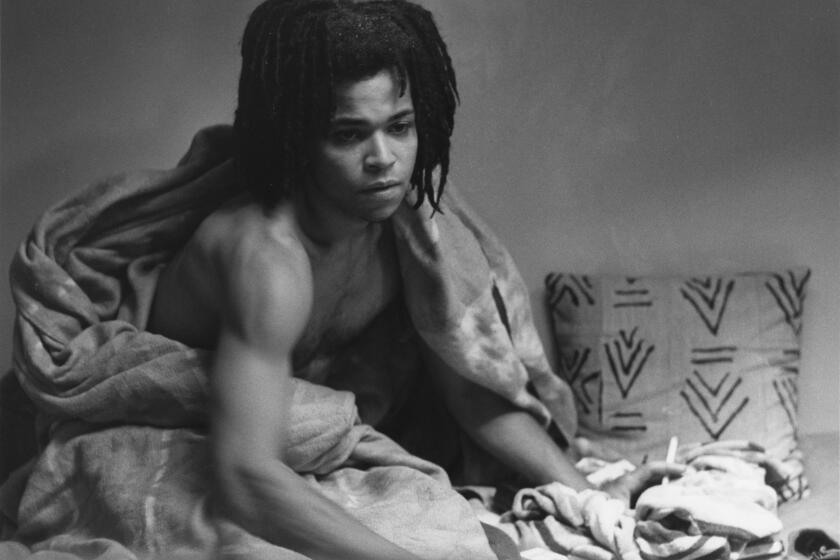

In “The Perfection,” Allison Williams and Logan Browning star as Charlotte and Lizzie, a pair of high-achieving cellists with a dark secret in common. After numerous twists and turns, the film arrives at an ending viewers will never see coming, which Shepard says was inspired by Korean cinema — particularly films like “Old Boy” and “The Handmaiden.”

“We started talking about how can we tell a bonkers story that is also fun, scary, erotic, horrible and yet at the same time wild,” said Shepard. “Plot twists definitely happen in American movies but not crazy ones,” said Shepard during a press day for the film. “So I thought, ‘Can I do a movie in which crazy plot twists happen and it still makes sense in the world that we’ve created?’

“As a filmmaker you’re trying to do something that people haven’t seen. So you give them something that satisfies their needs but that hopefully feels new or is presented in a new package.”

The Times caught up with Shepard to discuss spoilers, complicity and trying to tell a story about rape and revenge without making it exploitative. The interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

A big part of this movie is casting. What made Allison and Logan right for their roles?

I wrote the movie with Allison in mind. I’d worked with her on the [HBO] show “Girls,” and there was something about Allison where sometimes it’s hard to read what she’s thinking. I thought that would be perfect for this part, where you’re not supposed to really know whether you can trust her or what her true intentions are.

And with Logan … we auditioned everybody basically, and she just was the best actor. Allison’s incredibly smart and passionately articulate, and I needed the same thing from the other actress because not all actors are that way. I needed someone who was going to speak up for [herself] and challenge me. I mean, I’m a 54-year-old white guy. I wanted these two younger women to challenge me on certain things because this is subject matter that needed some challenging from a different point of view.

What was it like working with Allison post-”Girls”?

“Girls” was a beautiful experience in which we were in a very big cocoon of Lena Dunham’s creativity. Lena is a brilliant, strong, articulate and smart visionary filmmaker. And this was her home, that show. As a director, I got a lot of freedom, but it was ultimately about fulfilling Lena’s needs. It was one of the best jobs I’ve ever had, but we were all in that cocoon, so Allison was too. She developed that character [Marnie] over six years, but it came from Lena and Jenni Konner and Judd Apatow.

And with this movie, this is my movie. I mean, I co-wrote it with Eric and Nicole, but I directed it, I produced it with Stacey Reiss, it’s me. And Allison was the first actor to get the script, and so we got to create in a different way than we had worked on “Girls” because we were creating from the ground floor together, and it was really fun. If I could work with Allison for the rest of my career, I’d be super happy.

The film explores themes of retribution for sexual abuse and assault. How do you think that its reception will be influenced by the changing times?

Having these actors who were very vocal about the things that were important to them affected many things. At very end of the movie, Logan is torturing Steven Weber [as the abusive teacher Anton] and she’s hitting him and she’s like, “This is for what you did to me and this is for what you did to Charlotte and this is for what you did to every other person who believed you.” And Logan wrote that. That was her saying, “This is what I want to say.” And I was like, “Yeah, you’ve given me a gift.”

What do you want audiences to take away from the film?

Well, a few things. Hopefully one takeaway will be, “Wow, that was a bonkers movie.” And I want the conversation to be like, “It was crazy” and “I watched it again” or “I want to watch it again to see does it make sense the second time?”

It’s funny. When we showed it at Fantastic Fest, audiences really loved it and it was super fun as a filmmaker to be in an audience, especially that audience. But with the last images of the movie, which are really shocking, there was utter silence in the theater. Like it was weird; people just needed to comprehend it. As a filmmaker, that’s kind of what you want, stunned silence. Not the bad kind where it’s like, “Why did I just waste 90 minutes of my life?” Instead the stunned silence was like, “Whoa.”

What was it like filming the sex scene with the actresses as collaborators?

In the sex scene I was like, “You want to get rid of anything? It’s gone.” And I will never do a sex scene again without empowering the actors because you have to do that; that’s the world we live in. But it’s also the right thing. And Logan and Allison just felt a lot freer doing the scenes knowing that they had a final veto.

And that’s very interesting because I think that sex scene is really sexy and it could have been exploitative or stupid or just like a white male gaze or something, and instead I’d like to think that it’s like a really cool scene. You actually feel the heat between these two girls, and I think part of that is because the actors felt like they could get in the edit room and go “No.”

How did you walk the line to ensure the movie wasn’t veering into exploitation territory?

It’s a thin line. I mean, I had no interest in making an exploitation movie. But I talk about Korean cinema or even the cinema of Brian De Palma in the late ’70s and early ’80s, like “Dressed to Kill” or “Blow Out.” They’re stylish. There’s an art to them. So you can push the boundaries of things because you’re doing it in an artful way.

It’s a violent movie with very little violence in it. It’s a bloody movie with actually very little blood in it. It’s a rape movie with no rape in it, only suggested and not ever seen like you would normally see. It’s a revenge movie in which the revenge is very tough, but it’s warranted once the movie’s over. So it’s a lot of those things, and it’s a little bit of who I am as a human.

Let’s discuss a couple of specific choices: What’s the significance of Paloma’s complicity in Anton’s actions?

Here’s the thing: All the people at that academy had been abused themselves. So it’s a little tough because you have some sympathy on some level for anyone who’s been abused, and most people who are abusers were abused themselves. [But] Paloma allowed it. There was a moment in the movie where Charlotte’s like, “Please help me,” and Paloma’s like, “No.”

All it takes is someone helping: Had the church decided to not reinstate that priest, he wouldn’t be doing [what he did]. Had Paloma just said, “This is enough; we’re not doing this,” that wouldn’t happen. But she chose not to. So that was calculated and on purpose, but none of this was taken lightly. It’s a fun movie and we’re talking about deep stuff in it — but we’re thoughtful people or try to be.

What do you think Charlotte and Lizzie got from that final duet after they tortured Anton?

There’s a revenge ending to the movie that is satisfying, but then I wanted the last images of the movie to be difficult and beautiful: These two women playing this very beautiful instrument together because they’ve each lost a hand. So it’s just by nature a very unique and interesting visual. I thought it would be really cool. I also wanted Anton to be deformed by their hand and tortured. And at the same time, the part that’s really disturbing is that these girls still feel the need to play for him and that his ear is left unharmed and so he can hear them. But then the joke on set was that they probably played terribly. So all he’s hearing is imperfection and maybe that’s their torture.

So what do you think happens to these characters after the movie ends?

[Laughs] A lot of therapy.

follow me on twitter @sonaiyak

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.