Collective carries the beat of Belize

In his native Belize, Andy Palacio is frequently compared to another lion of Afro-Caribbean music, Bob Marley.

Like Marley, Palacio was an artistic pioneer and prophet of a musical genre shaped by the cross-currents of colonialism and slavery, yet characterized by the music’s spirit of alternately joyous and plaintive resiliency. And, like Marley, Palacio was cut down in his prime, at 47, in 2008, after suffering a series of small strokes.

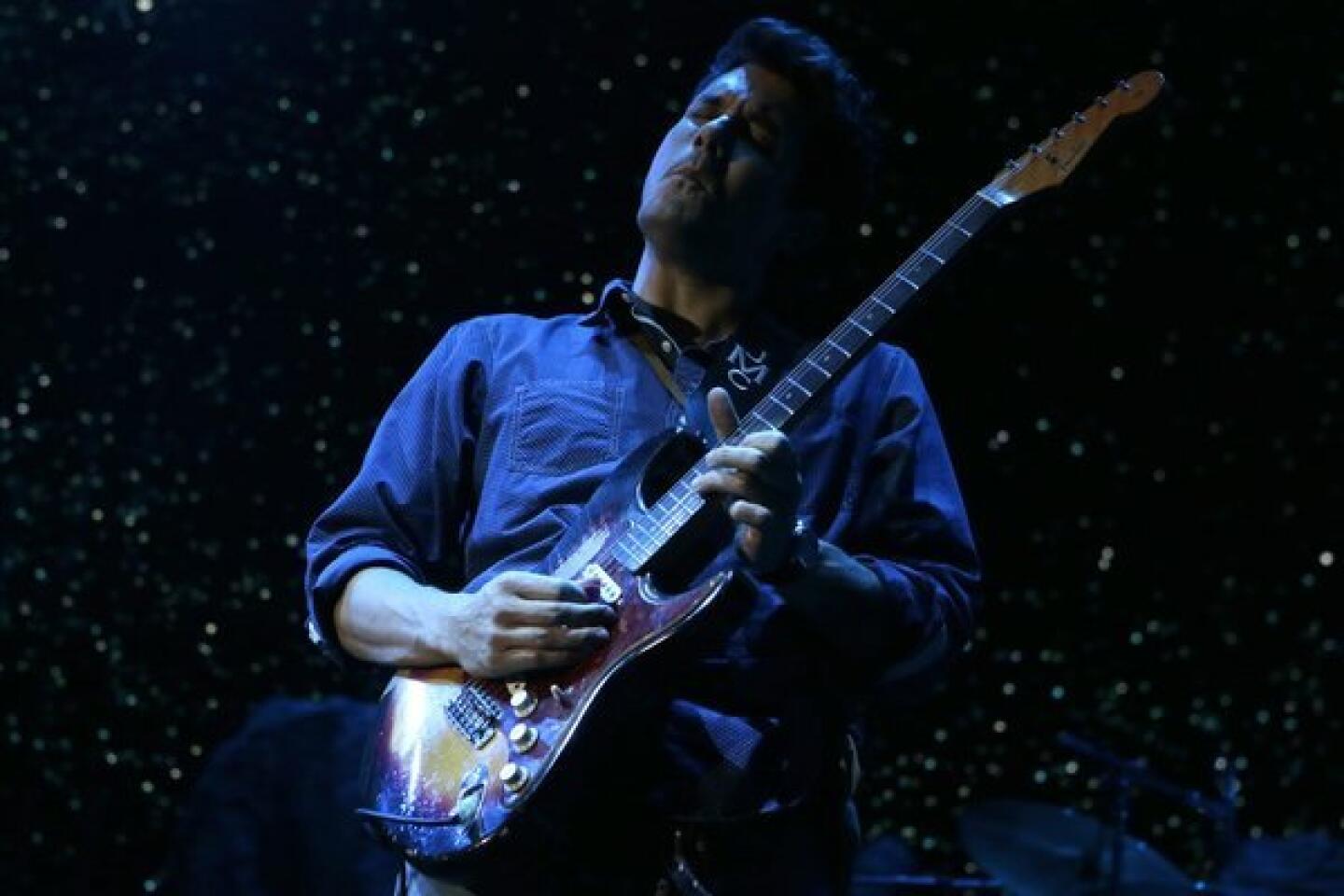

His passing was a harsh blow for Garifuna music, a soulful blend of African percussion and elegant guitar-driven melodies. Built around frank but poetic ruminations about daily life’s challenges, the music expresses the endangered cultural traditions of the Garifuna, or Garinagu, people, descendants of shipwrecked African slaves and Carib Indians who began migrating to Honduras, Nicaragua, Belize and the American South in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

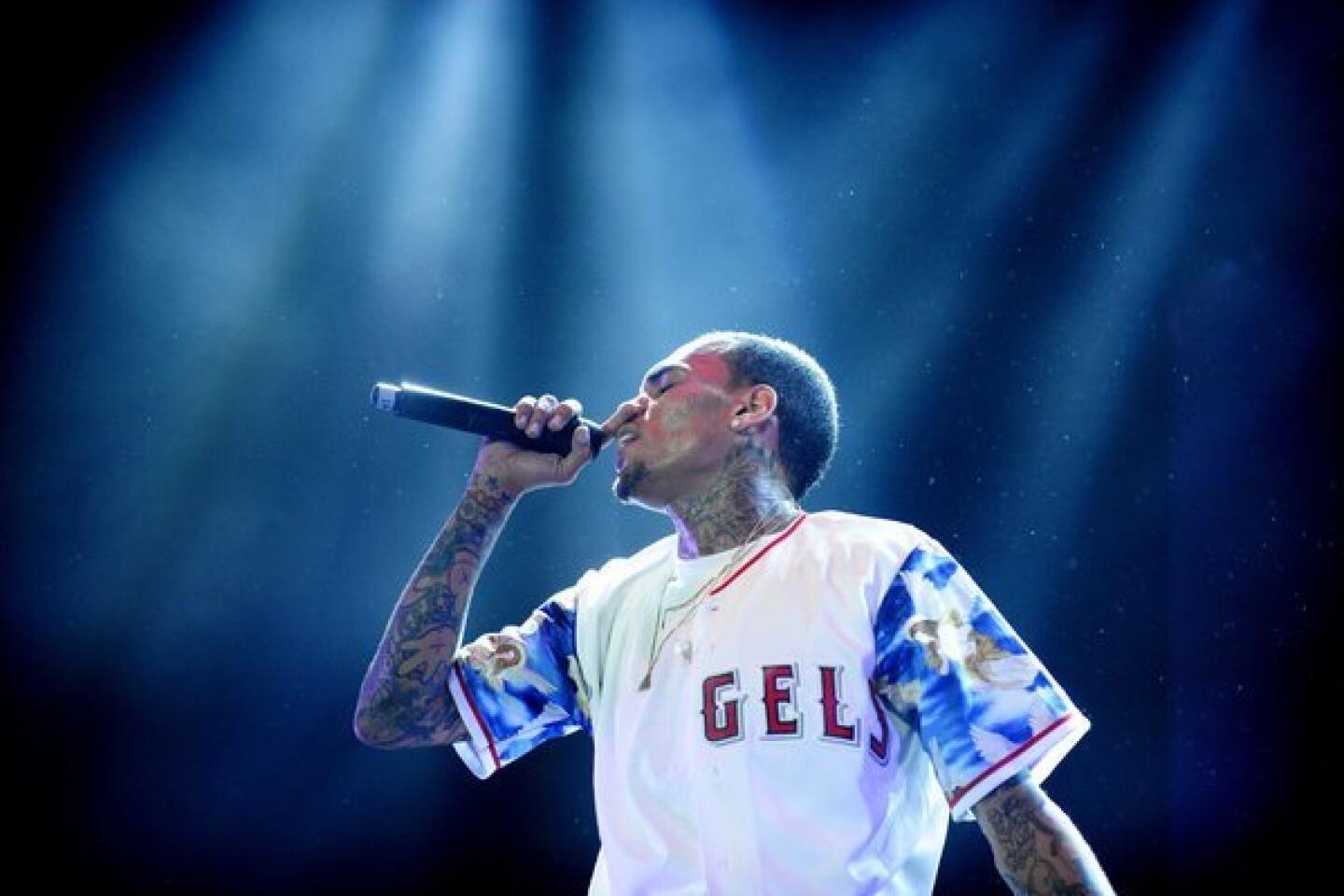

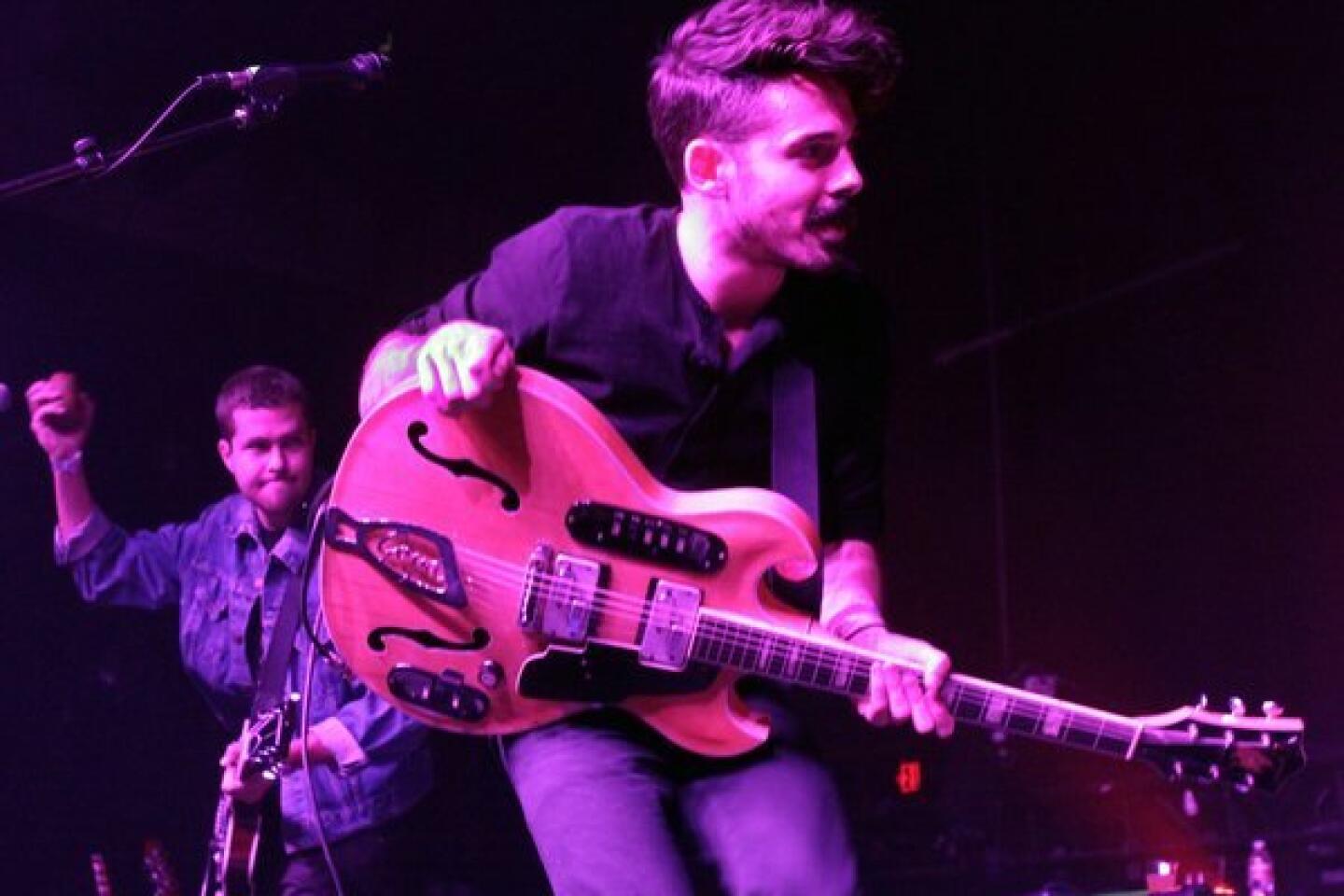

Although Palacio is gone, his former collaborators in the Garifuna Collective hope to evoke his legacy when they perform Thursday at the Levitt Pavilion at MacArthur Park.

TIMELINE: Summer’s must see concerts

“He was the best ambassador we could ever possibly have for our music, our culture and our country. The way that he took this story to the world, and the way that he connected and made this story a global one, that’s something that only he could have done,” said Ivan Duran, founder-owner of Stonetree Records, the Belizean company that teamed with the U.S. Cumbancha label to release “Wátina,” a 2007 album of Garifuna music.

The disc, on which Palacio performed for the last time, has become one of the bestselling albums in Belizean history and is regarded by aficionados as a classic, drawing comparisons with the Buena Vista Social Club, Afro-pop legend Fela Kuti and, yes, Marley.

Last month, Stonetree and Cumbancha released a follow-up, “Ayó” (“goodbye” in Garifuna), on which many of the musicians from “Wátina” return. Its release has accompanied a North American tour that in recent weeks has taken the musicians to major Canadian folk festivals.

“What this project means to us is mainly to carry on Andy Palacio’s lifelong work and lifelong dream, which is about teaching Garifuna, the Garifuna-ness, to Belize and the world,” said Joshua Arana, a drummer in the Collective, speaking by phone from Canada.

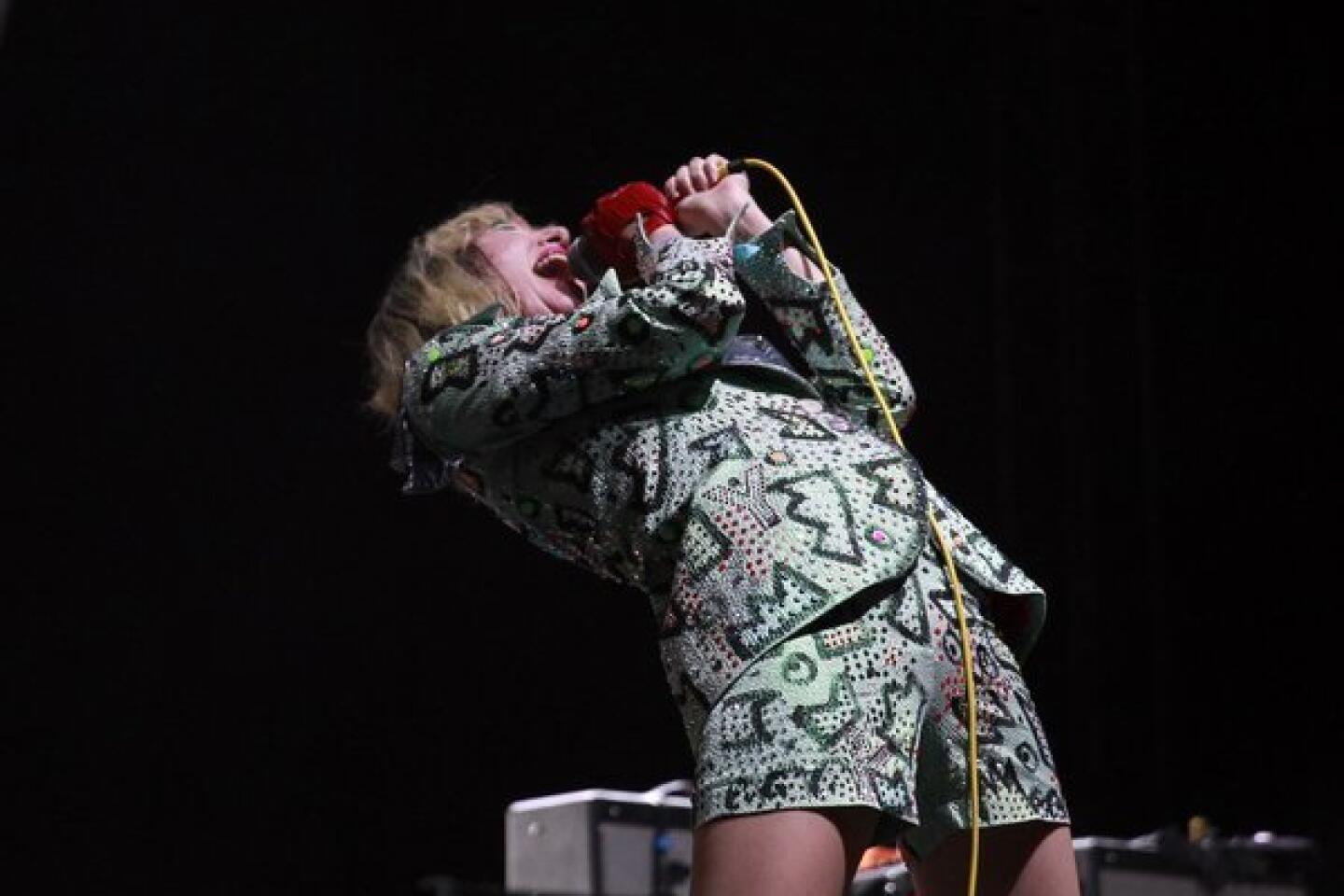

In one measure of Garifuna’s widening recognition, Canadian singer-songwriter Danny Michel this summer released an album with the Collective, “Black Birds Are Dancing Over Me.” A reviewer for Canada’s NOW magazine likened the record, which is the Collective’s first collaboration with another artist, to Paul Simon’s “Graceland.”

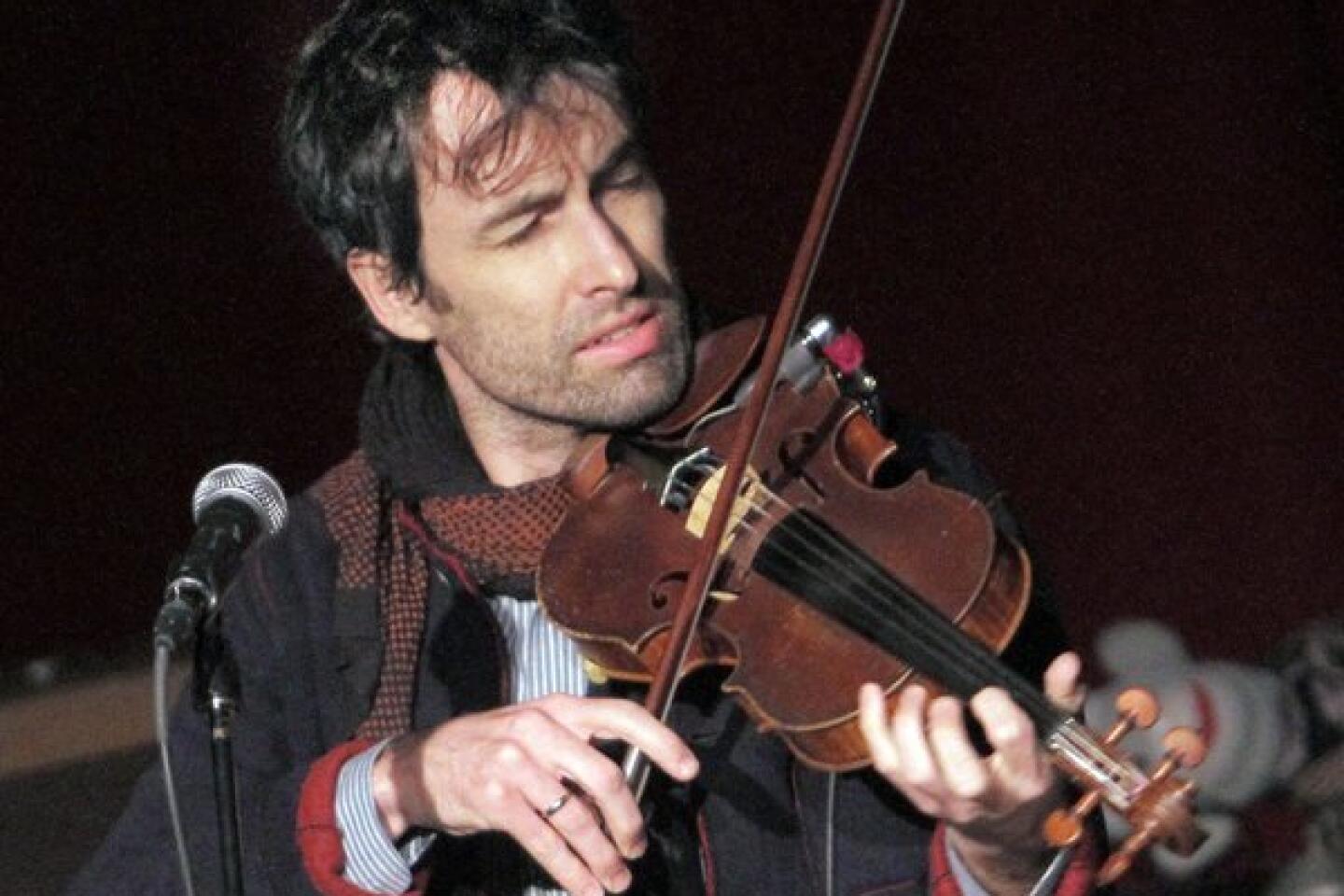

Michel, who’s accompanying seven Collective members on their current tour, first encountered Garifuna music during visits to Belize and volunteer service at a school in the Central American country.

“I just started listening to the music of the country and I discovered ‘Wátina,’ and I just loved it, and then I started digging in deeper and learning about Paul Nabor and some other artists,” said Michel, referring to another Belizean musical elder statesman of the melancholy yet rhythmically irrepressible genre known as paranda.

Instrumentally, the Garifuna sound derives from an interweaving of traditional drums; other percussion such as maracas, turtle shells and other scrapers; lead and rhythm guitars; and shared vocals, by three to five lead singers in the Collective’s case.

PHOTOS: Best albums of 2012 | Randall Roberts

Many of the songs on “Ayó” cast a bittersweet glance at traditional ways of life that have come under siege as Belize, one of the hemisphere’s poorest nations, transitions from a farming and fishing economy to one based on tourism. As tourist dollars have flowed into the country, living standards have crept up, but so has income inequality.

On the album’s second track, “Galuma” (“Calm”), singer Lloyd Augustine makes a plea that a fishing community much like his native Hopkins Village won’t sacrifice its old identity and ancestral values to make way for the modern world.

“He was making a comment on how all the young kids in Hopkins, now all they want is a fancy cellphone and buy clothes and all that hype stuff,” Duran said. “There’s a bunch of condos and those kind of places, they’re all gated. There’s a few big resorts. I mean, they’re not monstrous; we’re not talking Cancun here. But still, for a small village like Hopkins, it’s a big thing.”

Another track, “Gudemei” (“Poverty”), offers a wry commentary on people whose behavior changes depending on how their fortunes ebb and flow. “It’s kind of sending out a remember that you have to be the same in good and bad times,” Duran said. “It’s a very common theme, actually, in Garifuna culture.”

In one sense, the “Ayó” album and tour are a farewell gesture, not only to Palacio but to two other former Collective members who have passed on, singer-percussionists Justo Miranda and Giovanni “Ras” Chi. But it’s also an affirmation about going forward.

“We all see ourselves growing old with the Collective,” Duran said. “Maybe if Andy was still alive I wouldn’t be saying this. But the fact that he left us so early, at such a crucial moment, we have absolutely no choice but continuing this journey.”

reed.johnson@latimes

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.