Book review: ‘The Forgotten Founding Father’ by Joshua Kendall

The Forgotten Founding Father

Noah Webster’s Obsession and the Creation of an American Culture

Joshua Kendall

Putnam: 355 pp., $26.95

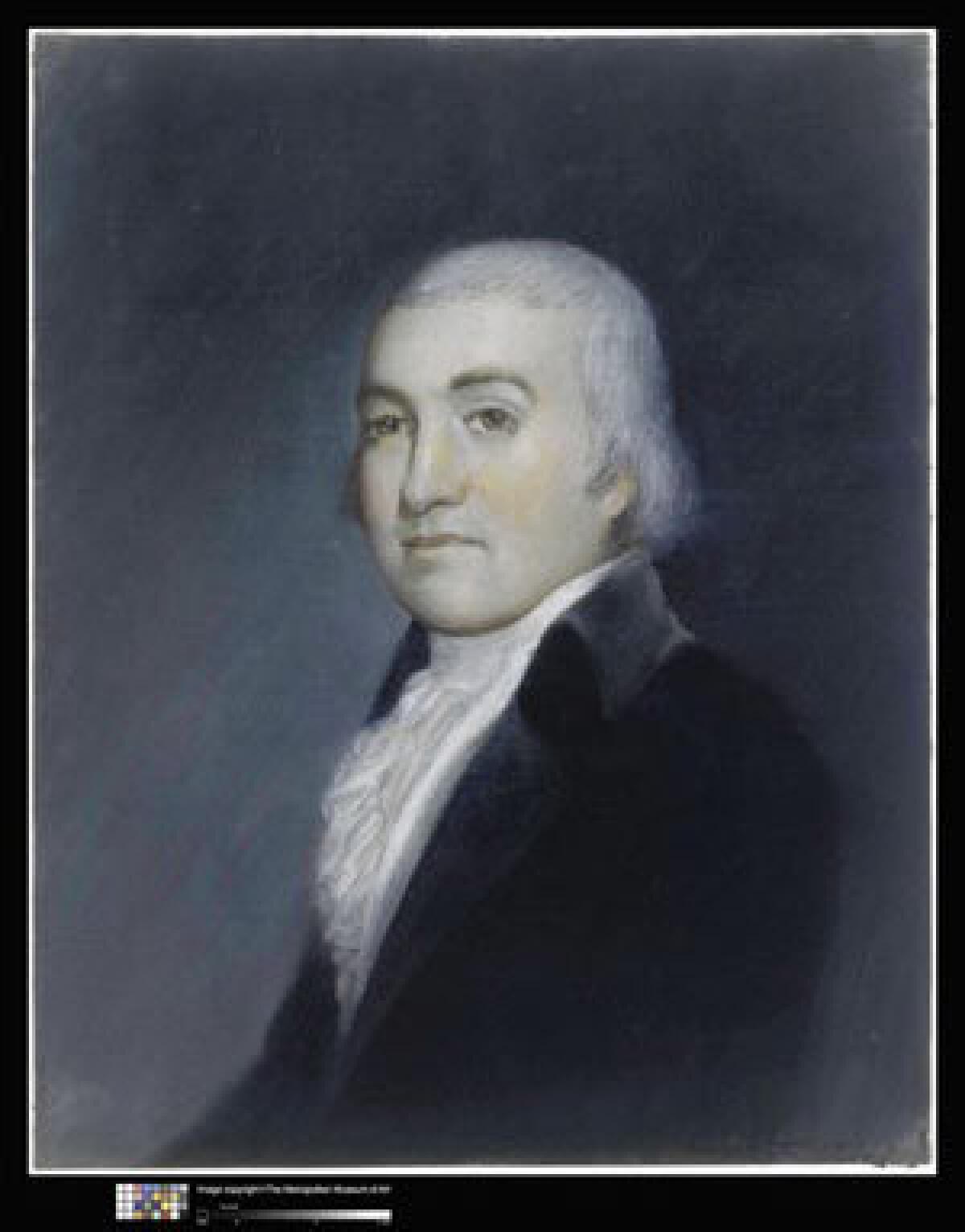

Reading Joshua Kendall’s smart new biography of the pioneering lexicographer Noah Webster Jr. (1758-1843) brings to mind a comment describing the late Supreme Court Justice Robert H. Jackson. Jackson was called “the most important public figure of the 20th century no one has ever heard of,” a tribute in recognition of the extraordinary work the jurist did when asked in 1945 by President Truman to serve as chief prosecutor at the Nuremberg trials.

Jackson, of course, has not by any means been lost to history, and neither for that matter has Webster, but both have been obliged through no fault of their own to occupy what is known in boxing circles as the undercard to the main event. They were both professionals of admirable skill and accomplishment but lacked the kind of star power that commands marquee status — especially over the long term.

FOR THE RECORD:

Book review: A review in the May 8 Arts & Books section of Joshua Kendall’s book “The Forgotten Founding Father” said that Samuel Johnson published his “Dictionary of the English Language” in 1775. The correct year was 1755. —

In the instance of Webster, the metaphor is particularly appropriate, given that the man was a tireless self-promoter who did everything he possibly could to make himself a household name, shamelessly seeking out the approbation of George Washington and Benjamin Franklin, for instance, and introducing promotional conventions such as the celebrity blurb and speaking tour that today are commonplace in publishing.

The quintessential New Englander’s frenetic efforts to secure recognition in his lifetime were not unsuccessful, either. By the end of the 19th century, his “Elementary Spelling Book” had recorded sales in the millions, second only to the Bible over that period, and provided the impetus for what Kendall suggests in “The Forgotten Founding Father” was America’s first national pastime, the spelling bee.

And his magnum opus, the “American Dictionary of the English Language,” did not do too shabbily either. First printed in 1828 after 28 years in the making — and nearly twice as large as his idol Samuel Johnson’s “Dictionary of the English Language” of 1775 — it included 70,000 words, all defined with a “purely American flavor,” and has been a staple, in various iterations, ever since, now appearing every 10 years or so as the “Merriam-Webster Collegiate Dictionary,” which has sold 56 million copies since 1898.

As popular as Webster’s books were, though, vast riches did not immediately come his way, with copyright laws — one of his pet projects — slow to be adopted by the various states, and royalties earned not nearly commensurate with books sold. “Webster had considerable cachet,” Kendall writes of his subject’s dire straits in the 1820s, “but little cash.” Not a person to take fools gladly either, Webster had it in him to rub people the wrong way; one anonymously written letter to the editor of a Philadelphia newspaper decried the “insufferable arrogance” of the man so evident in a public lecture.

Born in West Hartford, Conn., the son of a poor farmer, Webster was able to attend Yale College through great family sacrifice. A teacher and lecturer early in his career, he found his true calling with words. “I wish to enjoy life, but books and writing will ever be my principal pleasure,” he confided to Washington. “I must write; it is a happiness I cannot sacrifice.” For Webster, Kendall explains, “the payoff was in the daily compiling and arranging, which both mitigated his existential angst and gave him a sense of purpose.”

But Webster’s accomplishments went well beyond the making of books. He was variously a lawyer, patriot, amateur epidemiologist, statistician, pamphleteer, co-founder of Amherst College, and at Washington’s urging, editor of New York City’s first daily newspaper, the American Minerva. As Washington’s confidant at the Constitutional Convention, he had a voice in the proceedings, including his strong advocacy of several key principles, the need for “a supreme power at the head of the union” most notable among them. But his most enduring triumph was his relentless mission to get Americans to actually think of themselves as Americans.

Like his subject a Yale alumnus — summa cum laude, no less — Kendall is the author previously of “The Man Who Made Lists,” a much-admired life of Peter Mark Roget, the obsessive British list-maker who compiled the first thesaurus, a perfect book-end, so to speak, for a life of his American counterpart.

In one critical respect, Webster is a biographer’s dream, with an abundance of primary documents, including diaries, manuscripts, correspondence and public records available in numerous institutions, which Kendall has thoroughly mined. To his great credit, he does not let the wealth of material overwhelm his narrative, and he never loses sight of the fact that he is shaping the essence of an extraordinarily complex life, one that was uniquely American and well worth celebrating.

Basbanes is the author of numerous books, including the forthcoming “Common Bond,” a cultural history of paper and papermaking to be published by Alfred A. Knopf.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.