‘The Kid’ by Sapphire

On the very first page of “The Kid,” we learn Precious has died, leaving behind an orphan 9-year-old son, Abdul. Just like that, Sapphire, whose novel “Push” was adapted into one of 2009’s most acclaimed films, “Precious,” moves aside her troubled and inspiring creation so that this can be Abdul’s story.

Told from his point of view, it is a harrowing, sometimes bewildering tale. He didn’t fully grasp the severity of his mother’s AIDS; he doesn’t understand that he no longer has a home. His temporary place with a friend of his mother’s can’t last — they share a single bed — and when he is placed in foster care, it is in an environment far more hostile than he is prepared for.

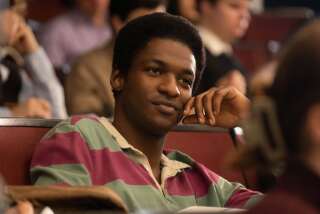

Eventually, he wakes up in a hospital and finds a new placement, in a Catholic boys’ home, where he goes by J.J. There, he is well educated by the men in charge, learning science and Shakespeare. He also suffers abuse at their hands, in sexual scenes that play out an inseparable combination of desire, twisted guardianship and self-loathing. Mature for his age and, as he later comes to understand, physically attractive, J.J. routinely performs sexual acts from early adolescence.

If it is little surprise, it is no less devastating when J.J. goes from victim to predator. He slips at night to the beds of younger boys, of weaker boys. In dreamlike language he narrates his sexual conquests: He is “flying,” he is “like a king,” for him, “it’s like ice cream and cake.” He doesn’t connect these boys’ terror and crying with the hatred he feels toward his own rapists; he even befriends one victim, Jaime, an act knitted with threads of loneliness and power. “He’s like a little child. I’m like the big father … I hold him in my lap, put my hand on his chest, his heart is beating, beating.”

Together he and Jaime have some fairly typical teenage adventures — financed by a few perverted adults — exploring the city and getting high. It’s on one of their unsanctioned outings that 6-foot-tall J.J., often mistaken for older than his 13 years, winds up crashing an African dance class. It’s life-changing.

“I listen to the beat, bah dah dah DAH!… The music rocks, my body turns into an ear hearing it. My body is not a stranger.… Here my body is my own, here I am a Crazy Horse dude who never gave up. Here I am like that dude Brother John told us the Schomburg got started by, here I am music, I never been to no police station for lies about little kids, here I got a mother and she ain’t no ho die of AIDS. Here in the beat is my life. The flute shrieks and I come again and again and can’t nobody stop me.”

For all that J.J.’s tribulations may be a grimly realistic scenario for impoverished, unparented youth, Sapphire realizes them with a highly stylized narrative that portrays J.J.’s fury, perplexity and passion. J.J.’s voice rises and skids to its own staccato rhythms. Often dipping into sexual fevers or dream states, it seems to nod to the subjective narrators of William Faulkner. The book also includes inscriptions from Flannery O’Connor’s “Wise Blood” (the narrator is not entirely bright) and Dostoevsky’s “Crime and Punishment” (the narrator is not entirely truthful).

At the boys’ home, J.J. remains both victimized and victimizer; although he appears to be on track for a college scholarship program, he’s too much of a target for the deeply emotionally conflicted men who have brought him up. When he’s caught perpetrating sexual violence, he’s delivered to a relative he didn’t know existed; she explains their family’s dirt-poor origins in a long passage marked by an extreme sexual and personal frankness. Desperate to find a place of belonging, he finds his way to the home of a dance teacher who will train him in exchange for sex.

Divided into four sections, it is the third in which J.J. — now Abdul once again — finds grace, working and working to become a dancer with promise. He slips between the cracks of the system, avoiding enrolling in school and instead taking dance classes at a number of places across the city. At 17 and passing for older, he becomes a founding member of an avant-garde dance troupe in Lower Manhattan. He has friends of a sort, and lovers whose encounters are as vividly detailed as his dances: “I continue with my dance, but now I’m not Lord Shiva, I’m King Kong … rising from the jungle with the whole city on my back. King Kong! Columns of glass, concrete, and steel go down with me as I plié, then fly into the sky as I rise.”

Though he is an unmistakable physical presence, Abdul’s identity becomes less clear. He keeps people at a remove, as his multiple identities and erasures form an indelible barrier. His growing reputation and new clique put pressure on that cloudy center, and he confronts fears about his parentage, figuring out who his father must be. It’s all too much for him.

Sapphire has taken the challenges her Kid faces and distilled them into a devastating voice, demanding and raw. When others speak — a girlfriend narrates her own, privileged devastations, and his relative tells the story of their family — the book loses momentum.

It is an accomplished work of art, but it is a grueling story, one whose depictions of brutality and desire may be too challenging for some readers — in fact, the excerpts here omit some of the strong language used throughout the book. In its final section, Abdul is institutionalized, swimming into consciousness only intermittently. He’s not sure where he is, or what’s he’s done. He’s been framed or he’s confused or he’s guilty. He is not sure of anything. But he is hard to forget.

The Kid

By Sapphire

Penguin Press: 376 pp., $25.95

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.