‘Steve Jobs’ review: Walter Isaacson’s biography mesmerizes

He was an abandoned child who grew up with the unshakable belief that he was destined to be a prince. How arrogant and sensible of him.

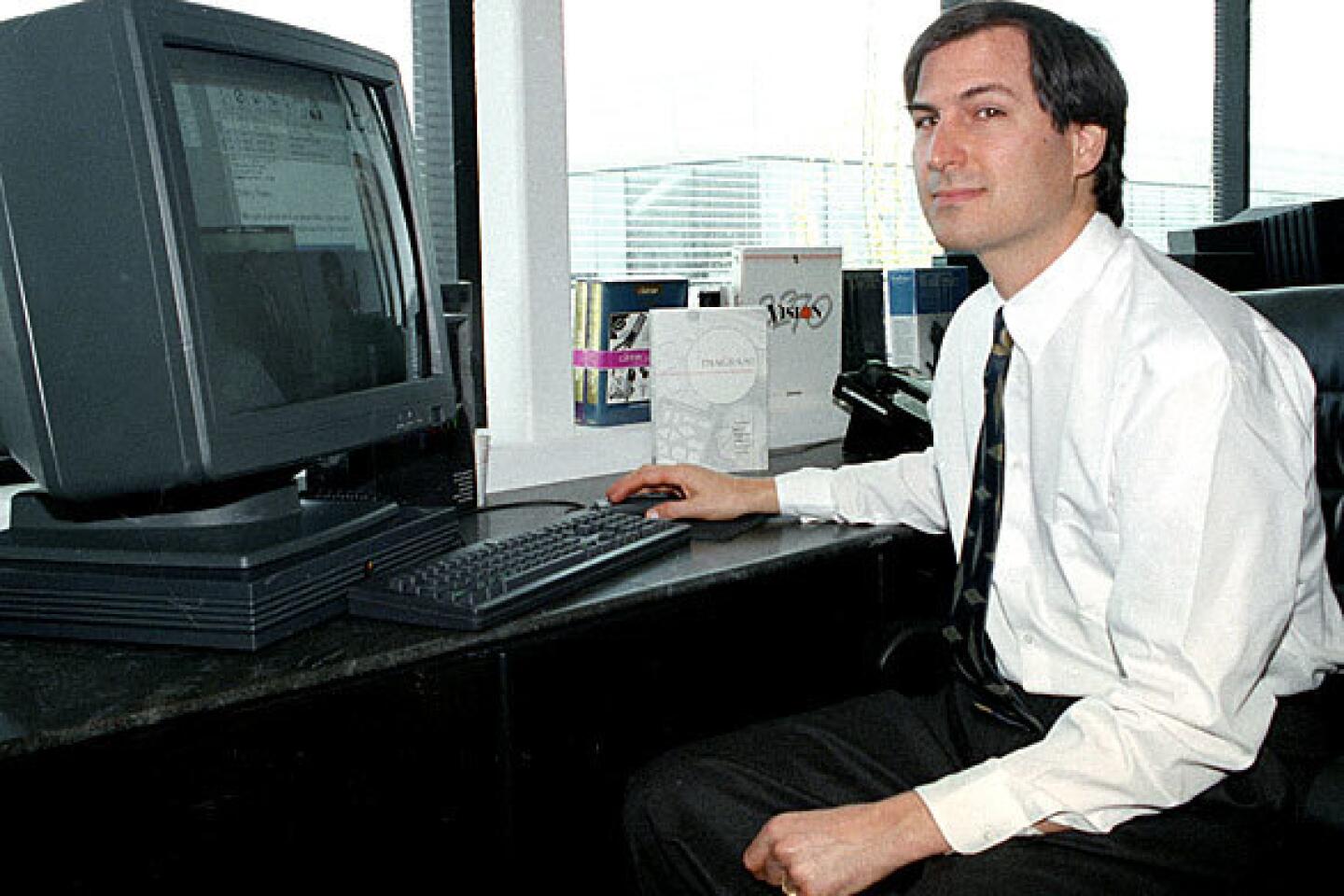

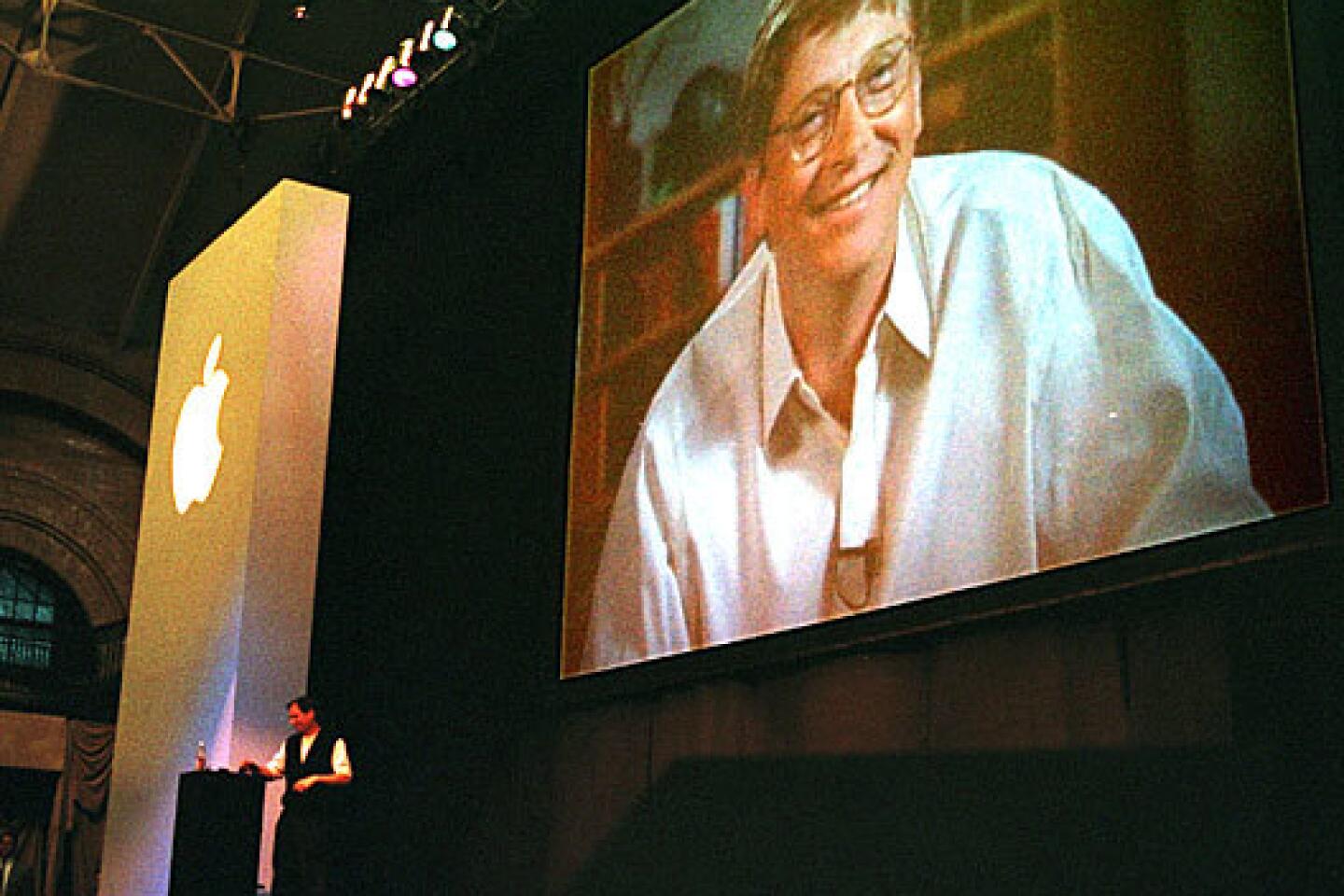

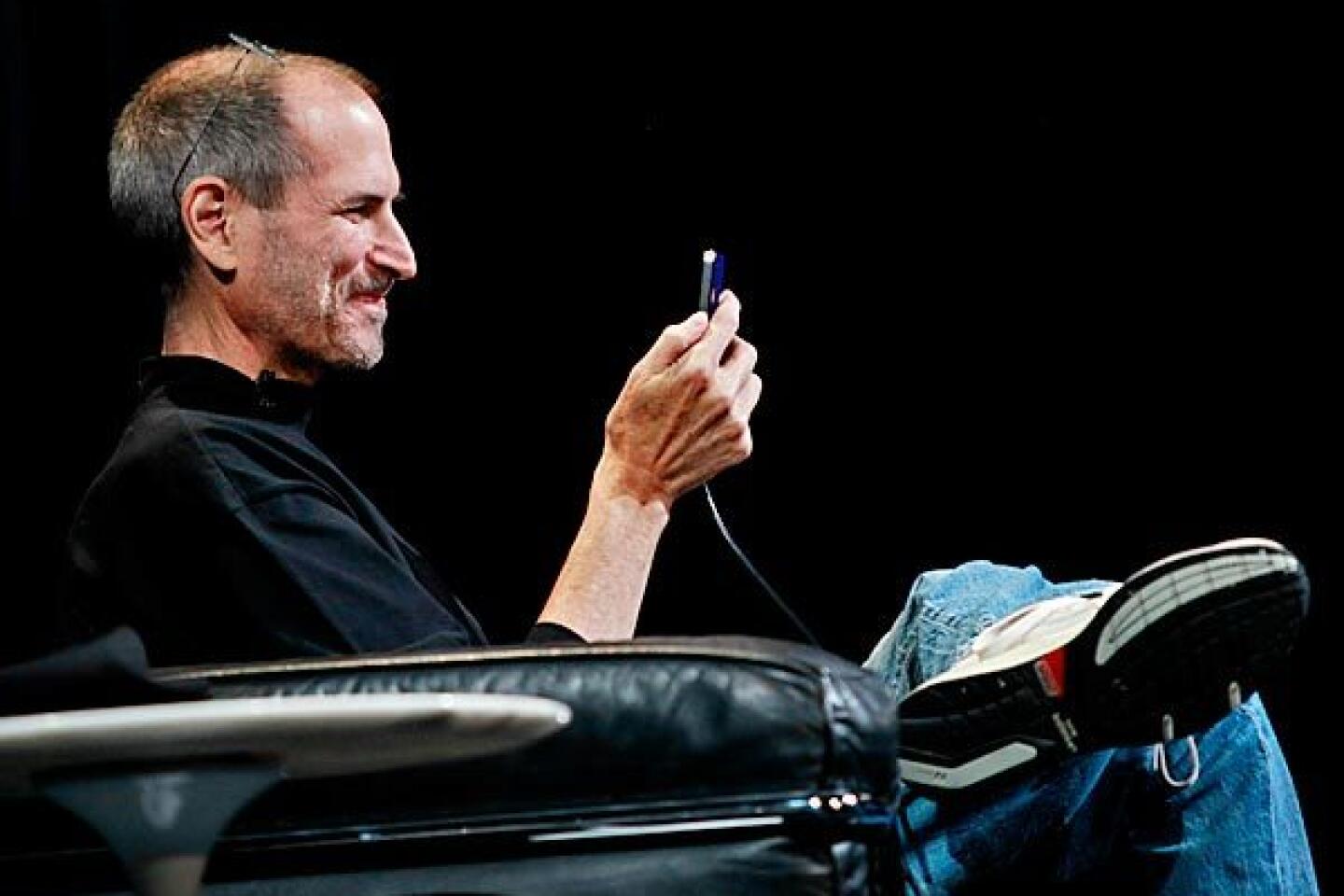

His personal hygiene was bad. He often wore no shoes and liked to stick his feet in the toilet. His food faddery was so extreme that he sometimes endangered his own health. While in a hospital for a liver transplant in 2009, he refused to wear a medical mask because he couldn’t stand the design. His own signature style, which featured jeans and a black turtleneck (Issey Miyake made him a lifetime supply of the latter, which he kept in a closet), was both anonymous and instantly recognizable. He was a control freak and a credit hog who burst into tears when he didn’t get what he wanted. He sometimes demeaned his girlfriends and his employees yet such was his charisma that they went on loving him. He lived in a Palo Alto house whose modest scale astounded his rival Bill Gates. He said that he came of age at a magical time, in the early 1970s, when his consciousness was raised by Zen, Bob Dylan, and the drug LSD.

FOR THE RECORD:

Steve Jobs: In the Oct. 29 Calendar section, a review of “Steve Jobs,” Walter Isaacson’s biography of the Apple co-founder, said that Jobs grew up in suburban Pal Alto (a misspelling of Palo Alto). In fact, he grew up in the communities of Mountain View and Los Altos. —

Full coverage: The life of Steve Jobs

J.P. Morgan or John Rockefeller, in other words, Steve Jobs wasn’t. Yet he died with a personal fortune of more than $8 billion (according to Forbes), having been a single-minded pioneer of the PC age, having created and built arguably the world’s most famous company, Apple, and having, in some way or another, touched all our lives. He was a visionary as ruthless and driven as any of the great first-generation American capitalists and his story already strikes us as a modern-day fable with a multitude of strange and enchanted details.

Journalist and biographer Walter Isaacson has previously written about Albert Einstein and Benjamin Franklin. Small wonder that Jobs picked him out, and Isaacson gives the Steve Jobs fairy tale a swift, full, and less than utterly flattering airing in a book that Jobs authorized himself and from whose stark white and black Apple-like cover he stares like a Zen digital master.

Jobs personally picked that mesmerizing image, while not having the time, or the health at that point, and maybe not the inclination either, to influence the text as a whole. Again, this is apt. Jobs drove his collaborators insane with his perfectionism yet he enabled them too. He knew the strengths and talents of others and was, for a tantrum-throwing Svengali, surprisingly self-aware. I’d guess that when he died less than a month ago he knew that Isaacson had served him fine.

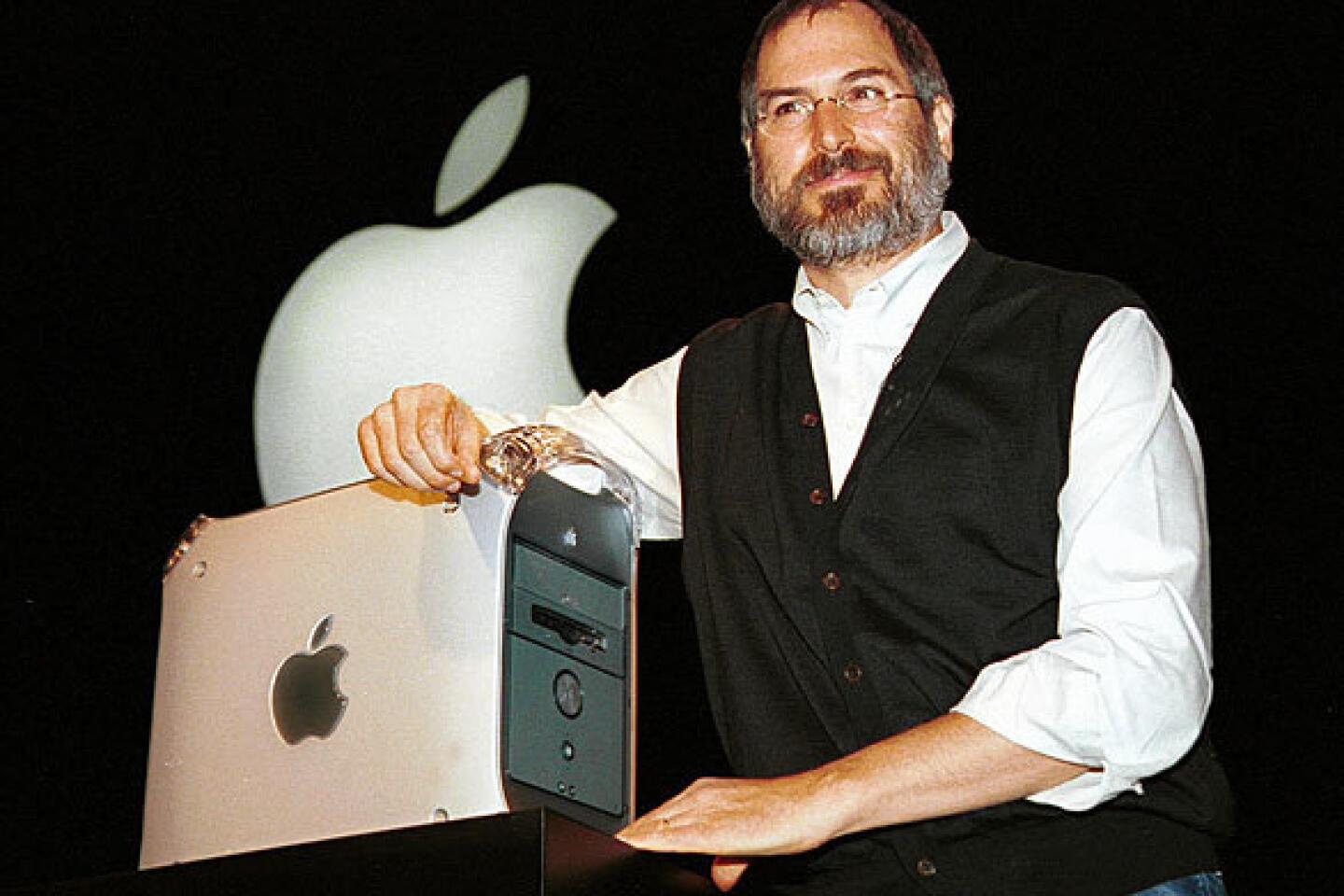

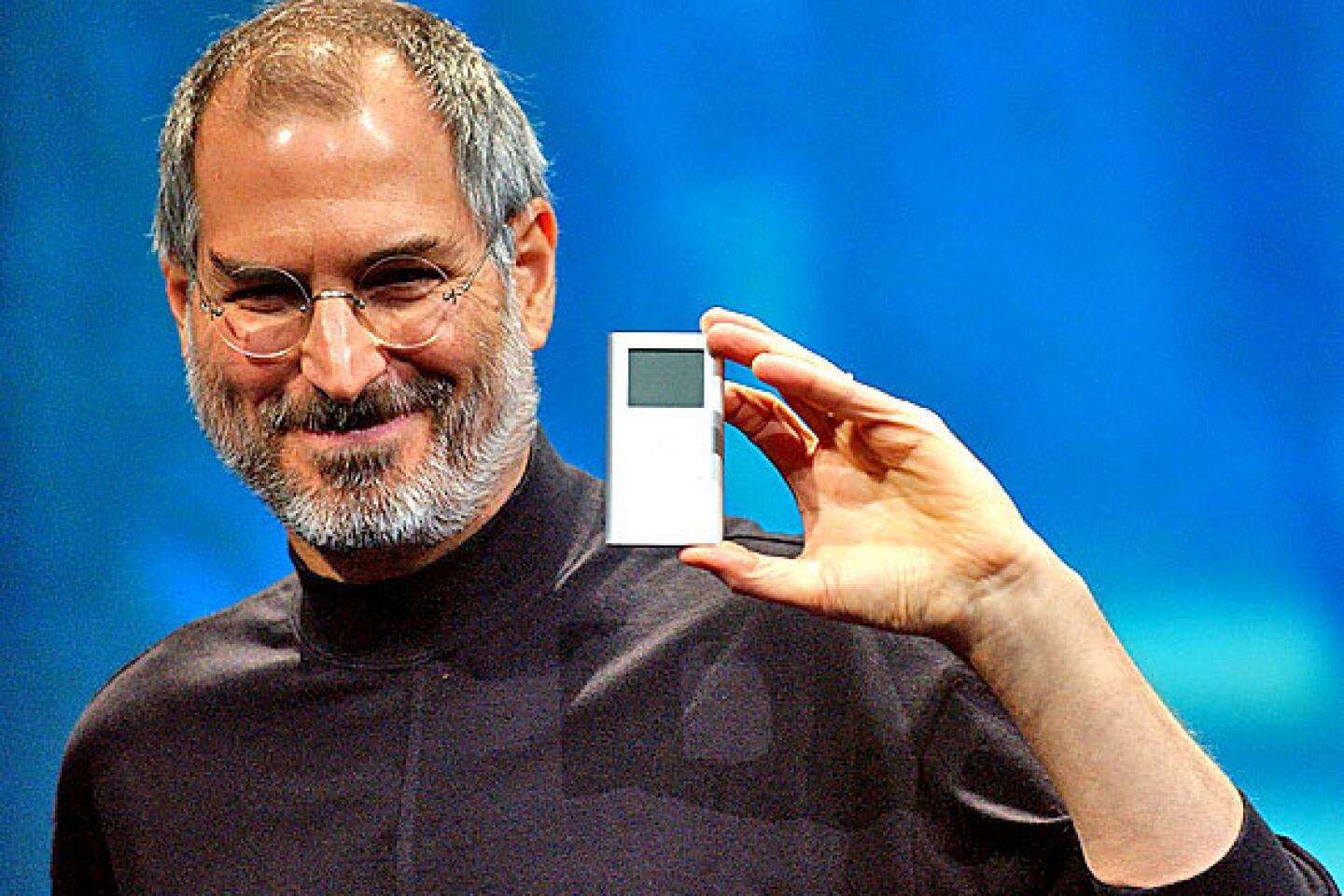

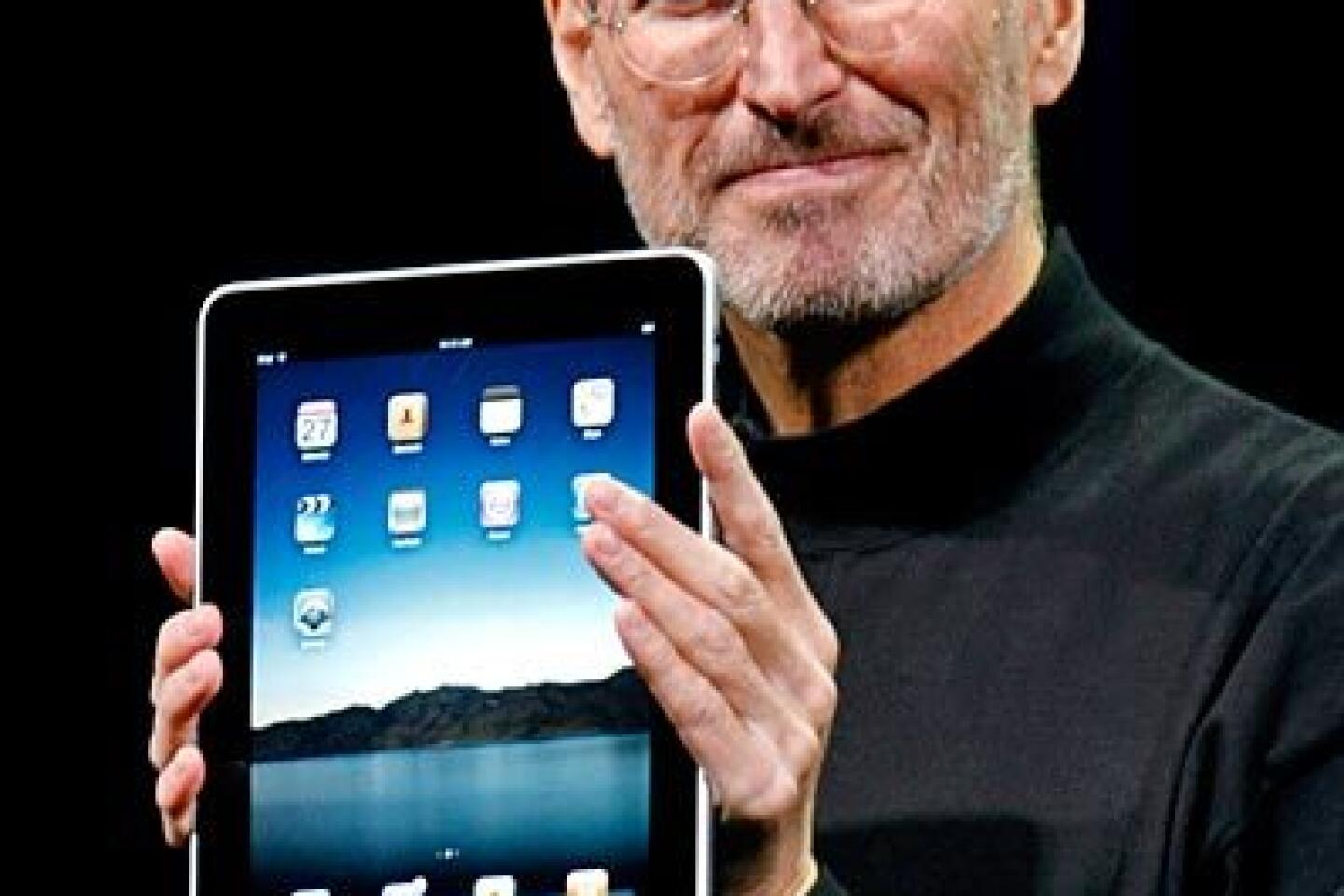

“The saga of Steve Jobs is the Silicon Valley creation myth writ large: launching a startup in his parents’ garage and building it into the world’s most valuable company. He didn’t invent many things outright, but he was a master at putting together ideas, art, and technology in ways that invented the future,” Isaacson writes. “He designed the Mac after appreciating the power of graphical interfaces in a way that Xerox was unable to do, and he created the iPod after grasping the joy of having a thousand songs in your pocket in a way that Sony, which had all the assets and heritage, could never accomplish. Some leaders push innovations by being good at the big picture. Others do so by mastering details. Jobs did both, relentlessly.”

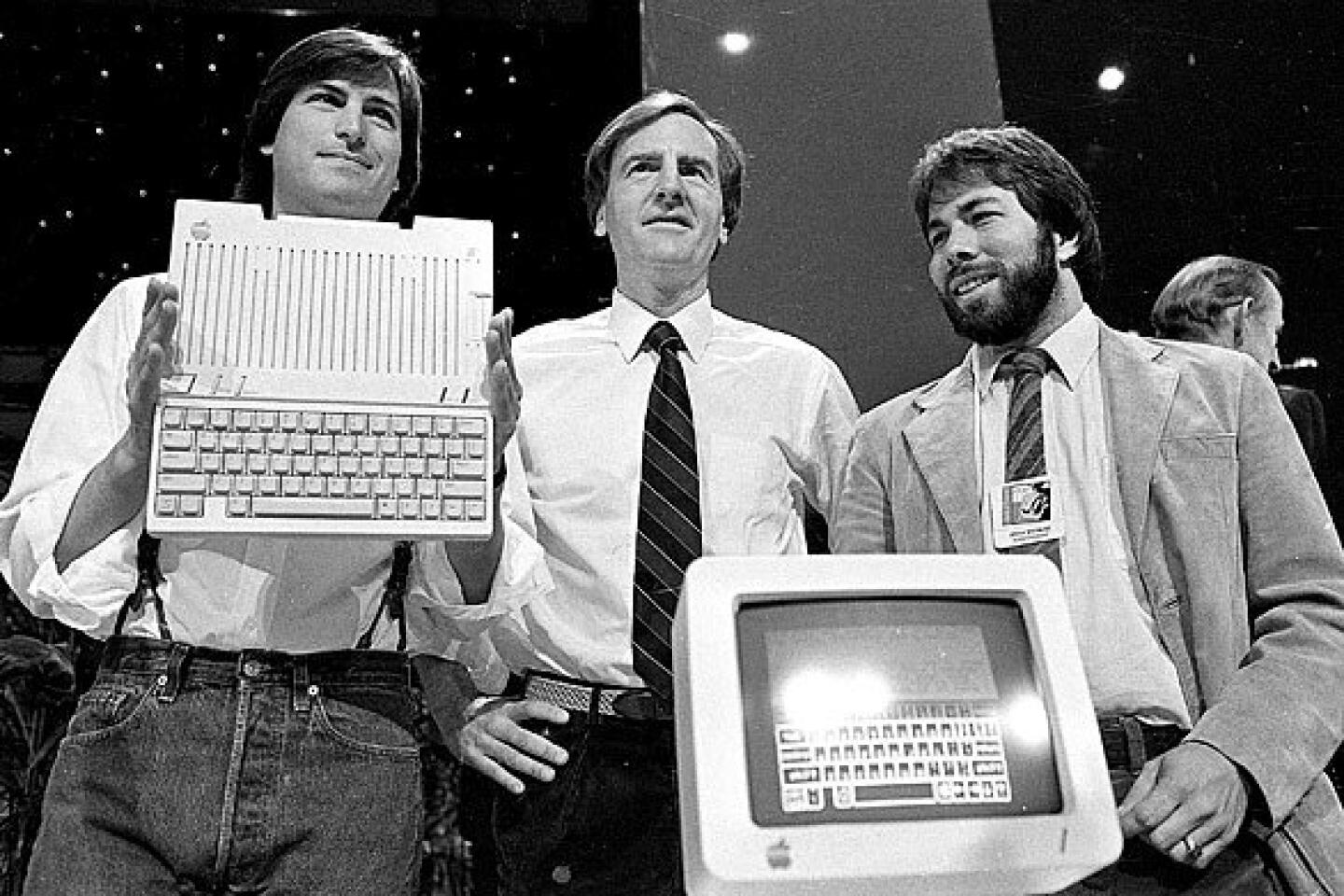

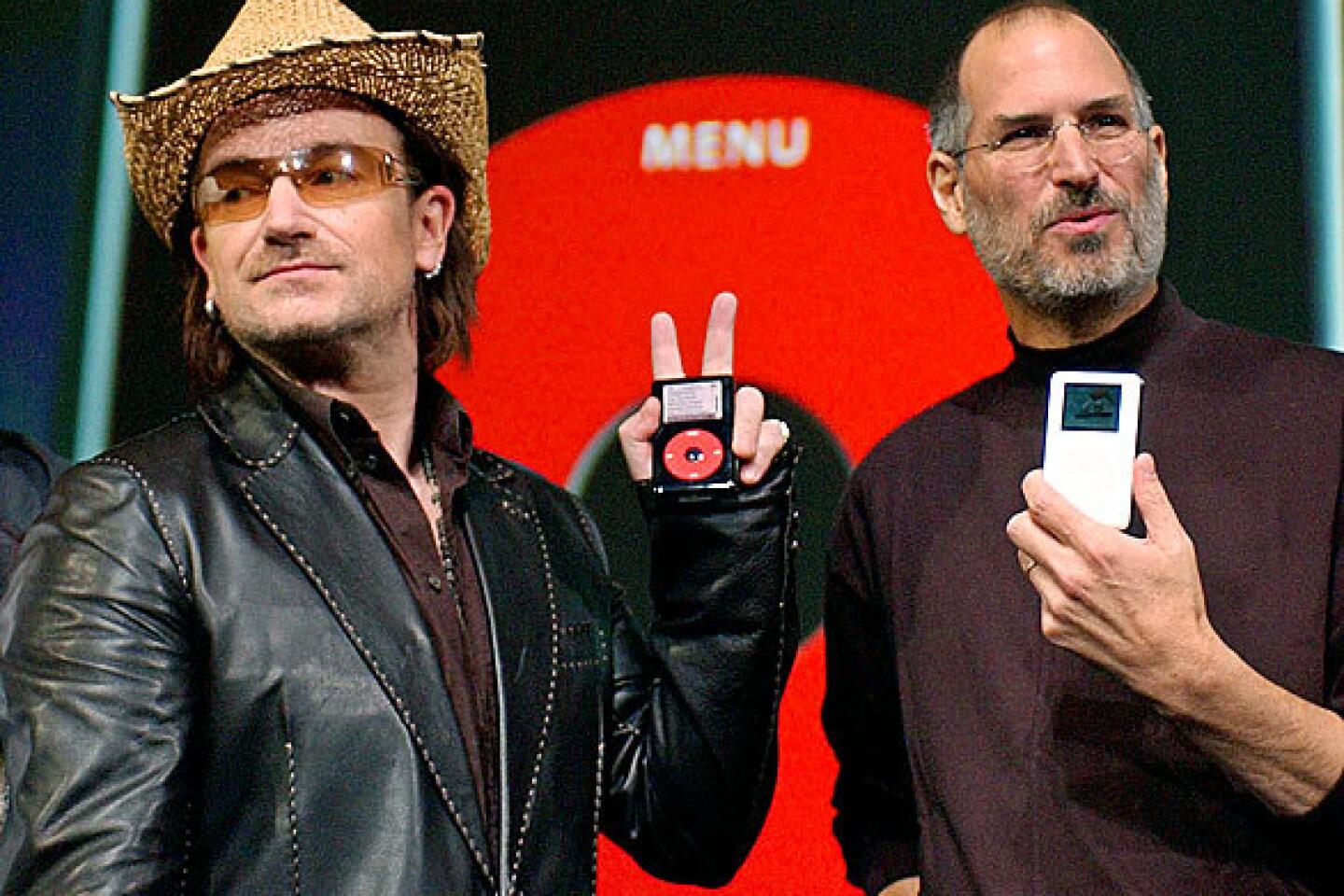

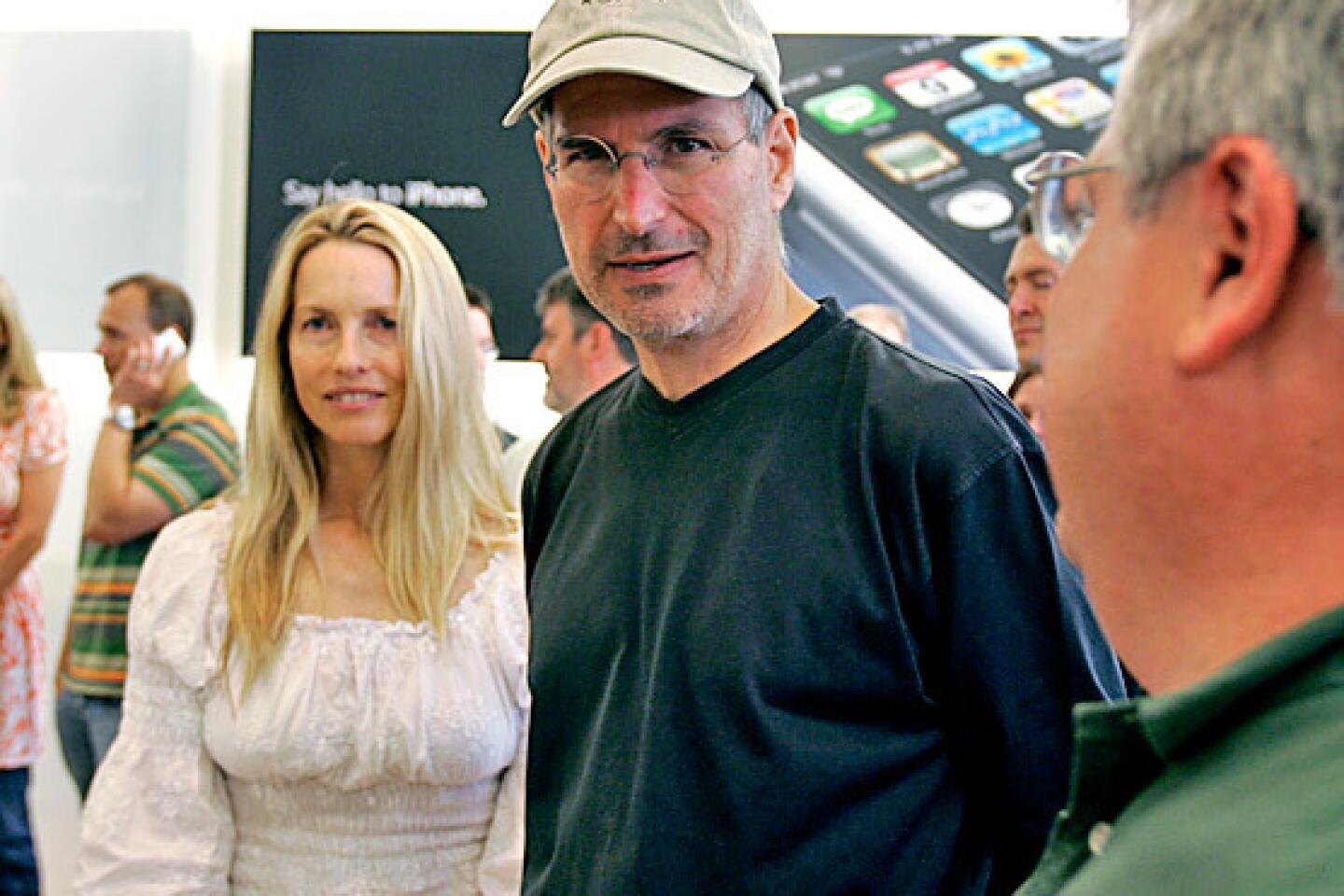

That’s the nub of the script that Isaacson follows. In assembling it he spent scores of hours with Jobs and interviewed hundreds of other people, including Jobs’ widow Laurene; a galaxy of his former girlfriends (among them Joan Baez and the writer Jennifer Egan); Jobs’ father by adoption; his blood sister, the novelist Mona Simpson; Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak; Apple design guru Jonathan “Jony” Ive; Gates; Bono; Rupert Murdoch; George Lucas; Yo-Yo Ma; Michael Eisner; Jeffrey Katzenberg; etc., etc.

The list of acknowledged sources is a who’s who of shakers and movers, and Isaacson weaves these voices together to guide and flesh out a narrative whose lineaments are already feeling like part of our cultural DNA.

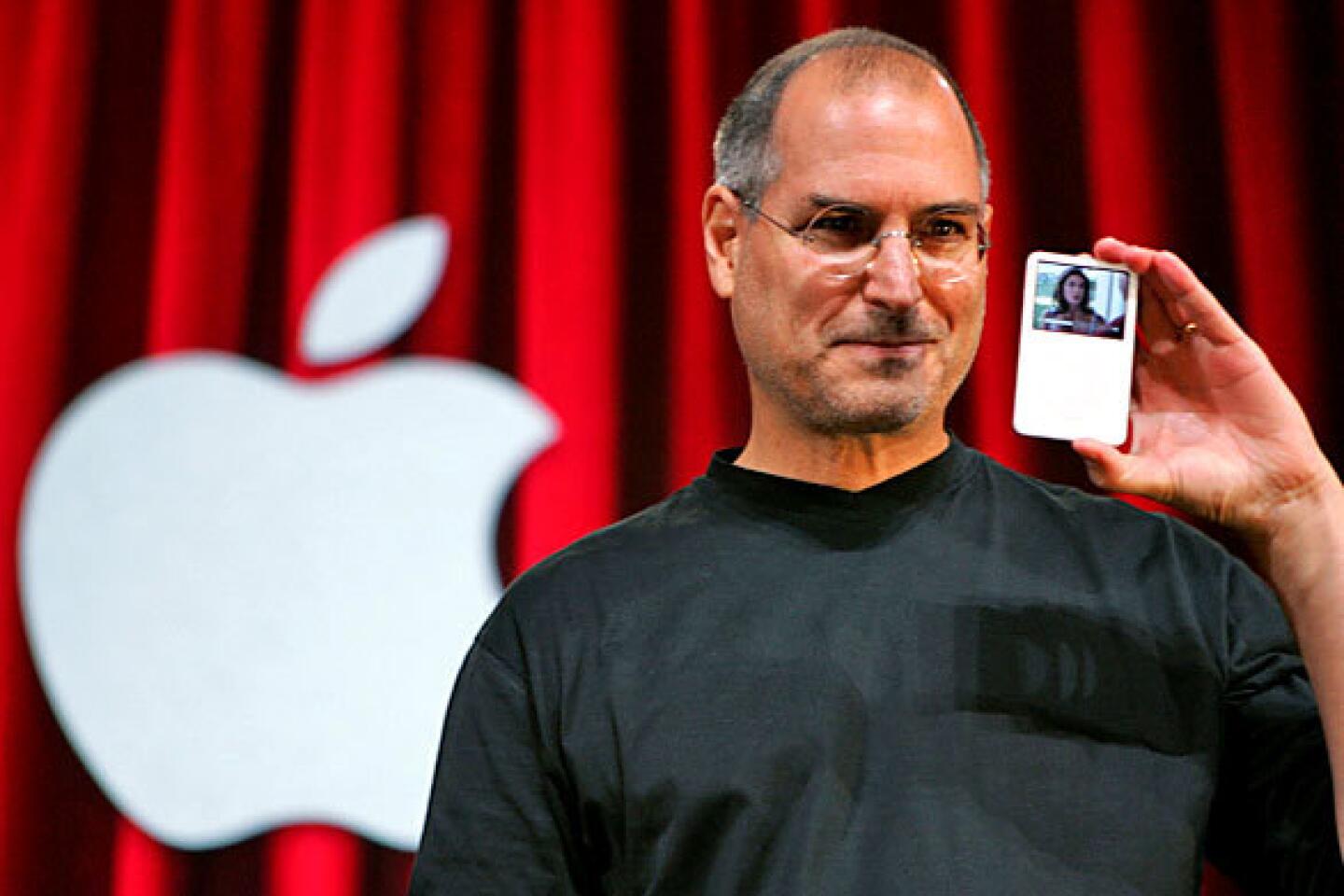

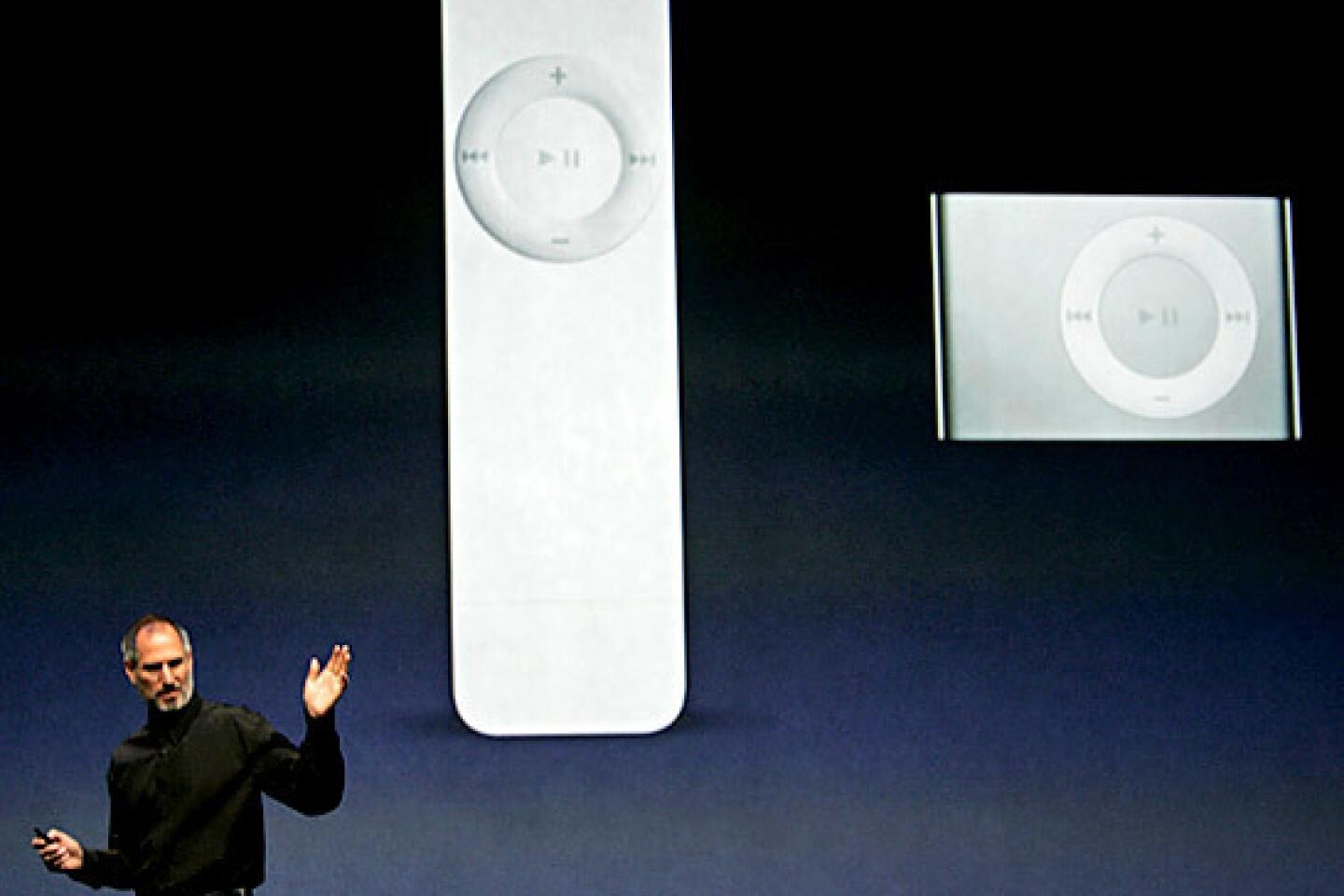

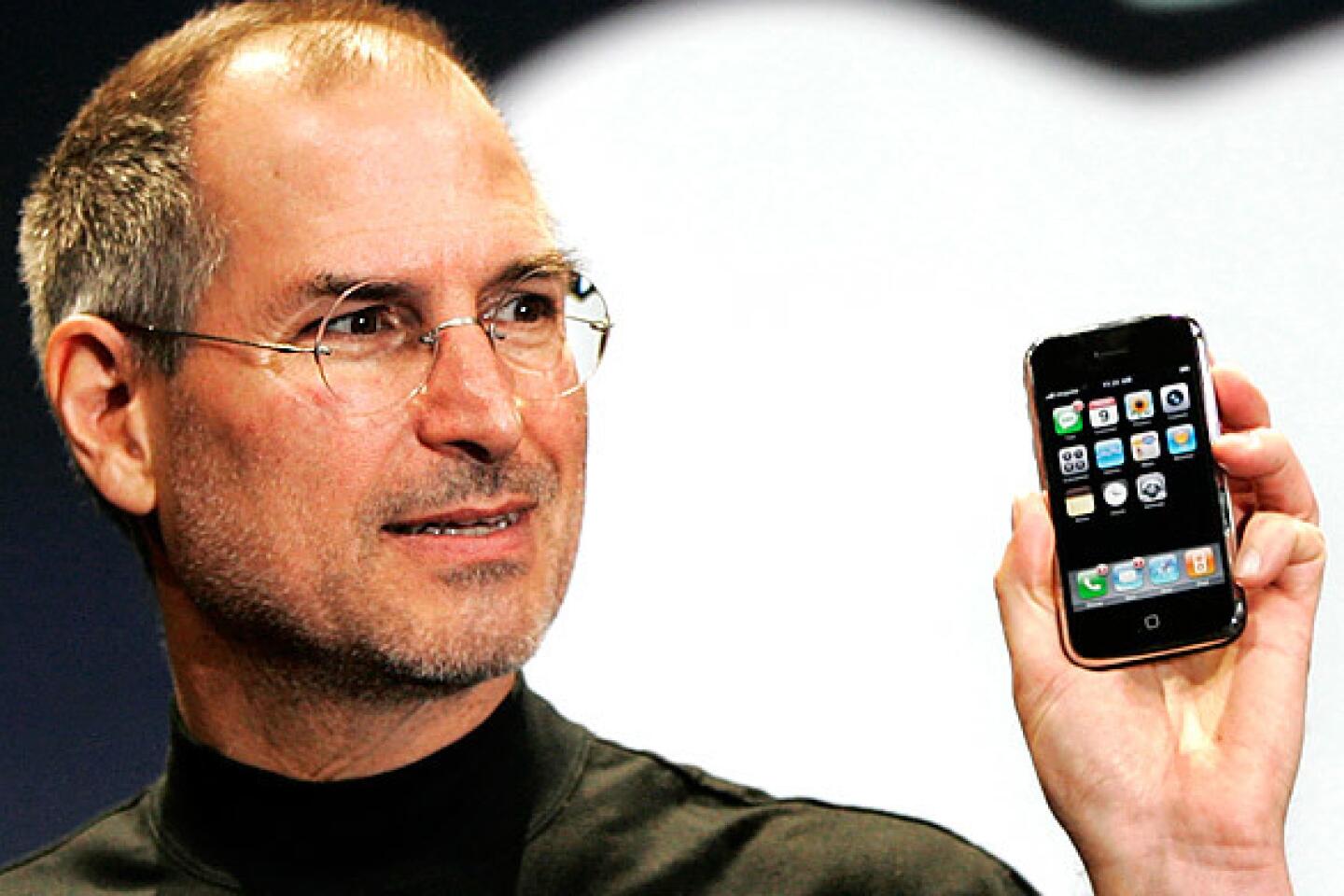

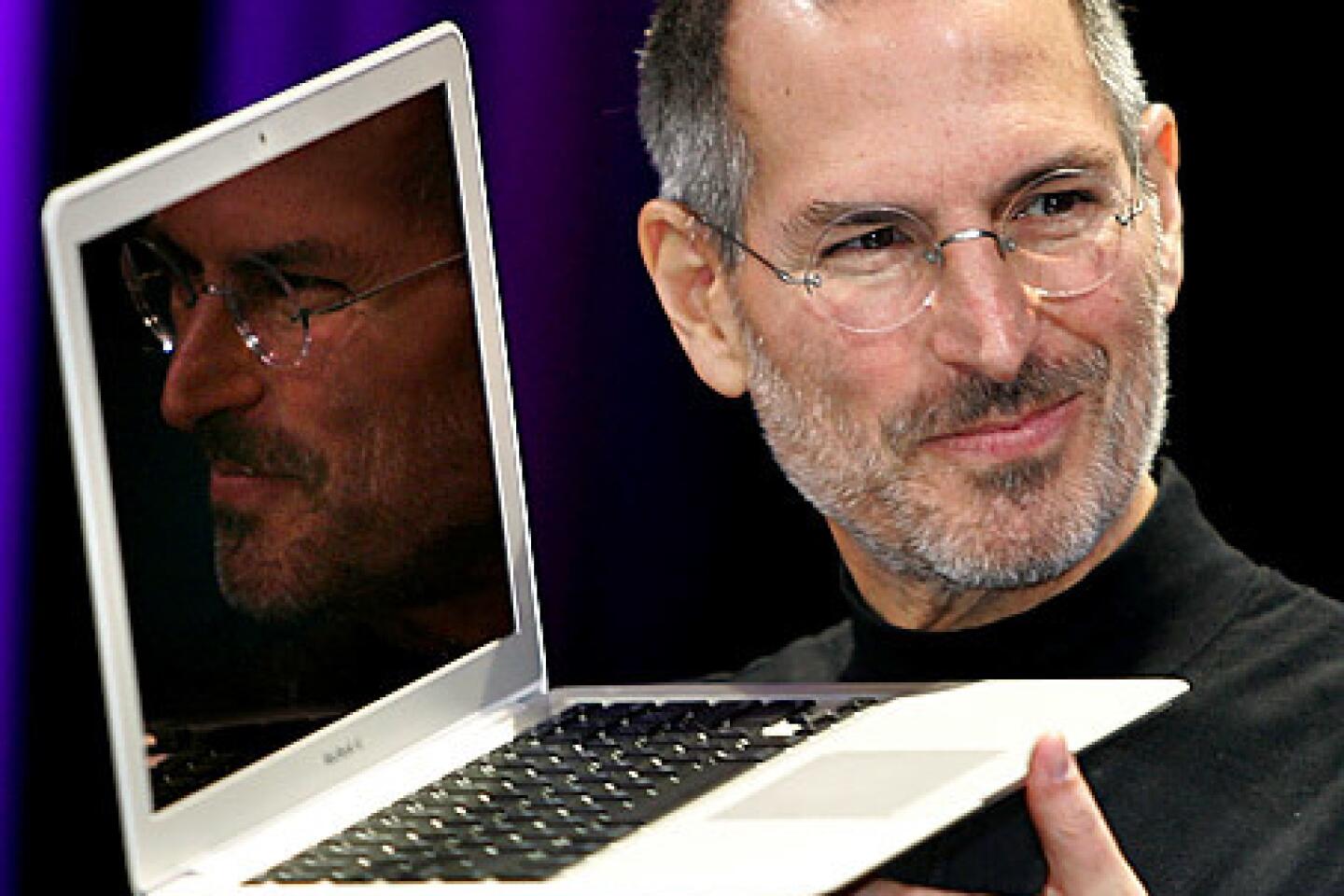

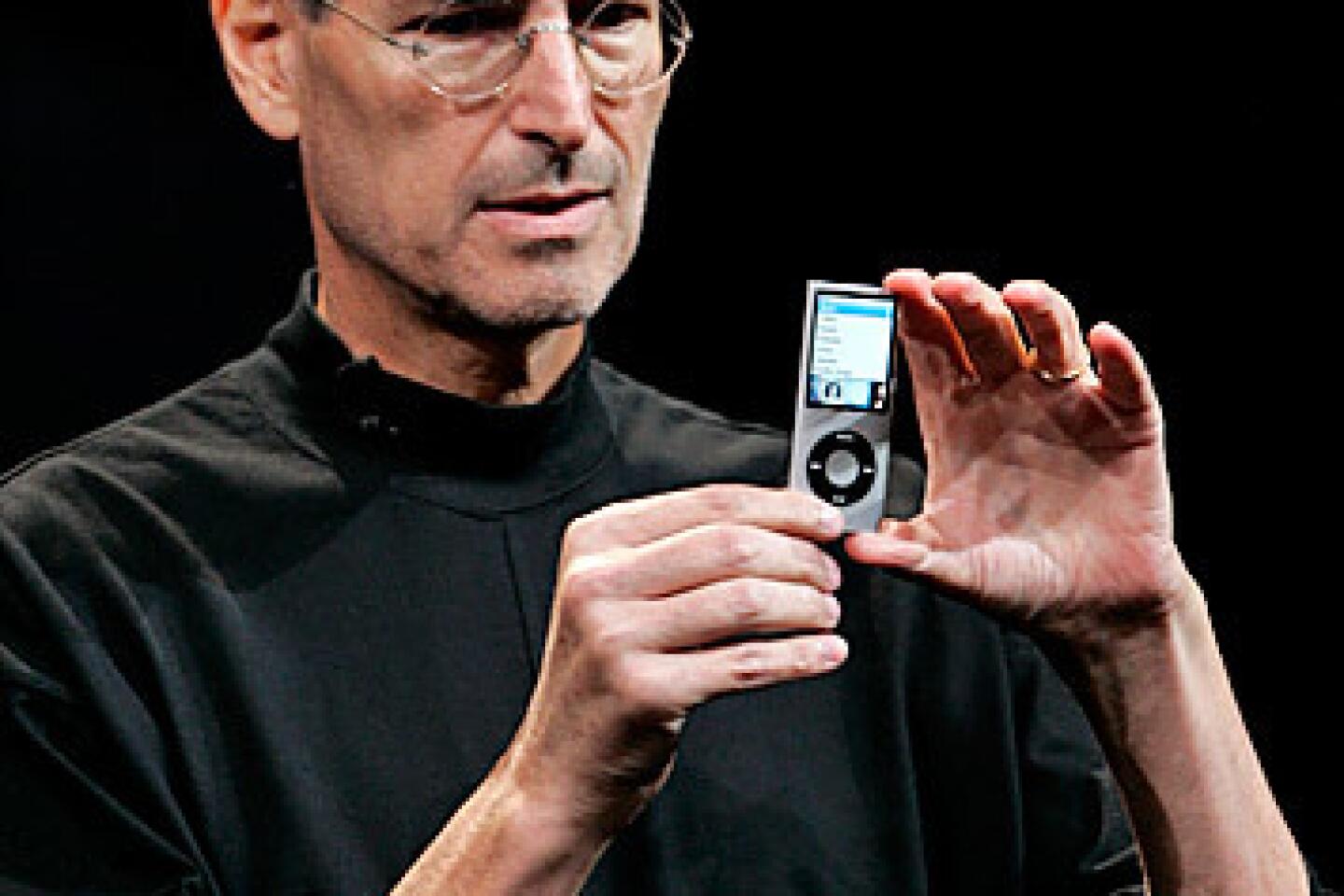

Jobs grows up in suburban Pal Alto with an adopted father he adores and who passes along a love for mechanics and electronics; he becomes a high school geek and freak with a fondness for “King Lear” and “Moby Dick,” then a college dropout; travels to India, works for Atari; with his partner Wozniak builds the first Apple computer and makes $100 million before he’s 25; plunges like Icarus, losing control of Apple in a July 4 power struggle in 1985; buys Pixar for a song from George Lucas and, with director John Lasseter, turns it into a wildly successful animation brand; gets Apple back and sees the advent of the Net as the conduit along which to build a vertically integrated consumer electronics company, with computers at the hub and a succession of revolutionary new devices — the iPod, the iPhone, and the iPad — as the spokes.

Jobs actually envisions all this, and brings it to pass. His mantras, his secret? Fewer products, better products. As explained to Isaacson: “Deciding what not to do is as important as deciding what to do.”

Jobs believed that producing technology requires intuition and creativity, while making art requires rigorous scientific discipline. That was maybe his key insight, and his subsequent mission, Isaacson tells us, was to marry science and art, those two troubled bedfellows, and then market the heck out of them. Like many seemingly simple plans, this was excruciatingly tough to execute, and Isaacson is very good when he takes us behind the scenes and into the nuts and bolts of certain key events: the building of the “Think Different” ad campaign, for instance, or the wondrous launch of the first iMac, or the plotting of the first Apple store, or the moment when, late in the process, Jobs and Ive looked at each other and realized — oops! — the screen on the already developed iPhone was way too small and so scrapped it all and started over.

It’s great stuff, and the communicated thrill of work and invention brings “Steve Jobs” to life. Sometimes, as when Bono twitters on about the birth of the snazzy black U2 iPod, pages descend into drooling celeb-chat. Generally, though, Isaacson sidesteps that sinkhole, and if what the reader gets feels like oral history as much as considered biographical judgment, that’s actually all to the good. The books asking whether Jobs was really a Da Vinci, or an Einstein, or a Howard Hughes or Citizen Kane are doubtless already trundling down the pipe, but this one will always feel necessary. Its very unmediated quality turns it almost into original source.

Full coverage: The life of Steve Jobs

“Using an Apple product could be as sublime as walking in one of the Zen gardens in Kyoto that Jobs loved and neither experience was created by worshiping at the altar of openness or by letting a thousand flowers bloom. Sometimes it’s nice to be in the hands of a control freak,” Isaacson writes. That’s pretty fawning, but I guess we can all go along with it at this point. Unlike Morgan and Rockefeller and others of that generation, Jobs was no monopolist and he didn’t milk the government. He was less interested in making money than in making beautiful and useful objects that would light up and shape the modern world. Put like that, he does seem a hero.

Rayner’s most recent book is “A Bright and Guilty Place: Murder, Corruption, and L.A.’s Scandalous Coming of Age.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.