Review: ‘American Canopy’ by Eric Rutkow should get out more

American Canopy

Trees, Forests and the Making of a Nation

Eric Rutkow

Scribner: 407 pp., $29

Every book has its quirks. In the case of the newly published history “American Canopy: Trees, Forests, and the Making of a Nation,” the prevailing eccentricity is that it’s not primarily about trees. The leitmotif of author Eric Rutkow is wood, chiefly how North American virgin forest gave rise to a new nation, and how the U.S. has reduced that resource from close to a billion acres of ancient woodland to what is now more like 750 million acres of often young trees.

As Rutkow tells it, timber is so basic to the American story that it even drove colonization. Seventeenth century Britain needed massive old pines to sustain its tall ship navy. “Pilgrims and Puritans may have arrived in America to discover an uncorrupted life,” Rutkow notes, “but that didn’t mean their backers shared this enthusiasm.” Soon the Eastern seaboard colonies were rotten with shipwrights. American independence did nothing to stall consumption; a young nation ran through pristine woodland at such a rate that by the1840s in Concord, Mass., when Henry David Thoreau retreated from civilization to contemplate nature, whistles of Boston-bound trains echoed across Walden Pond.

Meanwhile, the railroads driving westward expansion steadily chewed through genuine wilderness. Among their myriad uses, America’s timberlands were felled for railway carriages, bridges and track ties. Husbandry was a foreign concept. By the early 20th century, it was estimated that as much as 45% of America’s felled forests had been wasted in off-cuts and sawdust.

As logging industrialized, poor men became rich, and a rich landscape became poor. After arriving in America in 1852 as an 18-year-old German immigrant, Frederick Weyerhaeuser later controlled a logging empire valued at $70 million. Apart from canny purchasing of timberlands around the Great Lakes, his masterstroke was forming a syndicate of formerly rival lumber companies. By breaking logjams of wood being floated down the Mississippi, everyone’s production improved; at the same time, cut land around the Great Lakes became a tinderbox. In 1871, Wisconsin’s Peshtigo fire seared 2,000 square miles and claimed more than a thousand lives. In the Badger State alone, more fires followed in 1891, 1894, 1897, 1908, 1910, 1923, 1931 and 1936. “Losing half a million acres in a year was almost commonplace,” Rutkow observes.

As Weyerhaeuser’s saws turned from the Great Lakes to the Pacific Northwest, rival timber barons began working the Southern pine belts in Virginia, Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, southern Arkansas and eastern Texas. The more timber cut and milled by American lumbermen, the more ways an evolving wood industry devised to use it. By the 1870s, newspapers once called “rags” because they were printed on recycled cloth were increasingly printed on wood pulp, a cheap new material about to make the fortunes of Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst.

Rutkow credits pulp with no less than democratizing reading, transforming food storage and revolutionizing personal hygiene. As always, the losers were the trees. However, by the turn of the 20th century, rapacious cutting finally forced the creation of protected timber reserves that became America’s national forests. But, as Rutkow’s book concludes, the coming threats are not necessarily the old problem of cut-and-run logging but climate change, fire, disease and pestilence. If the book’s unbearably vivid accounts of past ravages of chestnut blight and Dutch elm disease are anything to go by, forest management is even more urgent today.

Rutkow lets drop in the acknowledgments that he worked on “American Canopy” for “more than half a decade.” If that’s a roundabout way of saying that he worked on it for about six years, here is a suggestion that he give it another six. This very good book deserves reading now, but it also feels like a work in progress — one that could be (but isn’t yet) a masterpiece.

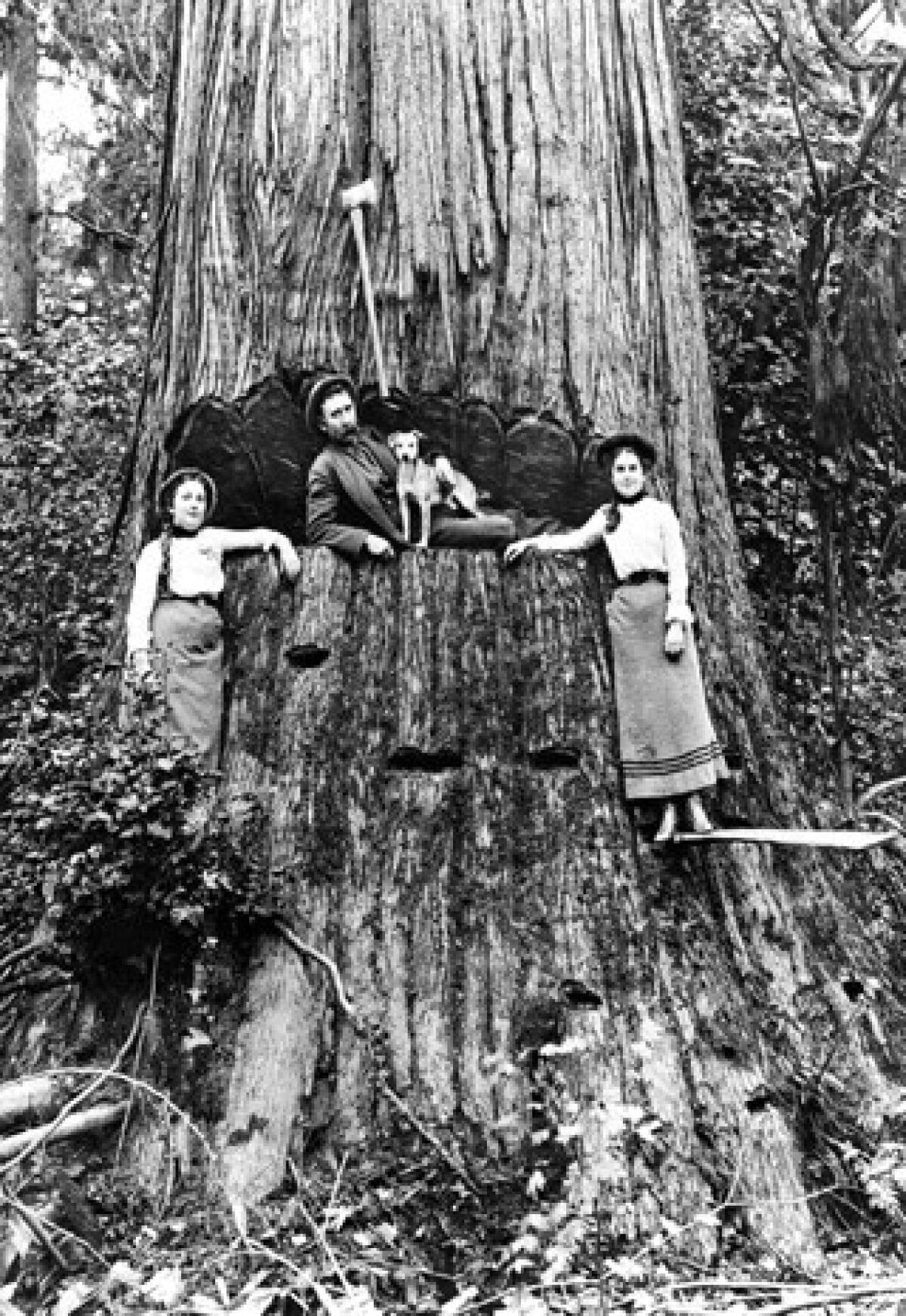

To do for forests what “Cadillac Desert” did for water, Rutkow needs to get out of the New York Public Library Allen Room and tour Appalachia in the era of mountain top removal. He needs to see what climate change and fire are doing to the vanishing pinyon forests of New Mexico, update his knowledge about logging in the Cascades. There is so little description of actual woods and trees in “American Canopy” that one can’t be sure if he knows a cedar from a pine.

The diversions he takes into ornamental horticulture and urban greening, along with chapters about Johnny Appleseed and citrus vogues read as if he went out drinking with Michael Pollan and John McPhee and the men somehow had their themes mixed up at hatcheck. In this new book on native timber, stray horticultural trivia amounts to nervous ornament. These incongruous passages also highlight the most screaming omission from “American Canopy,” which is any reference to Native American forestry practices, as if before Europeans, before tall ships, there were no canoes.

Green is Los Angeles-based journalist who covers Western water issues at chanceofrain.com and is working on a book about the Great Basin.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.