‘So Much for That: A Novel’ by Lionel Shriver

So Much for That

A Novel

Lionel Shriver

Harper: 438 pp., $25.99

Toward the end of her gleefully mutinous new novel, “So Much for That,” Lionel Shriver reveals the provenance of her beleaguered protagonist’s name, Shep Knacker. In bygone England, a knacker was someone who bought burned-out farm animals for conversion into fertilizer.

We’ll get to the relevance of that, but anyone with a casual acquaintance with Yiddish may also hear in Shep’s evocative moniker echoes of the term schlep naches, which loosely translates as deriving pleasure from the achievements of others.

I doubt whether Shriver intended that echo; she’s the daughter of a Presbyterian minister, and schadenfreude informs her writing more than any joy in others’ happiness -- but the Yiddish allusion lends a bracingly ironic ring to the burdens that poor Shep will have to schlep before naches steps in to rescue him.

We first meet this hard-working Brooklyn contractor packing to make the escape to Africa he has long dreamed of and meticulously planned. Shep adores his wife and two children and would love for them to come along, but either way, he sees “the Afterlife” as a means to flee a lifetime of bondage to those who prey on his good nature and reflexive compliance.

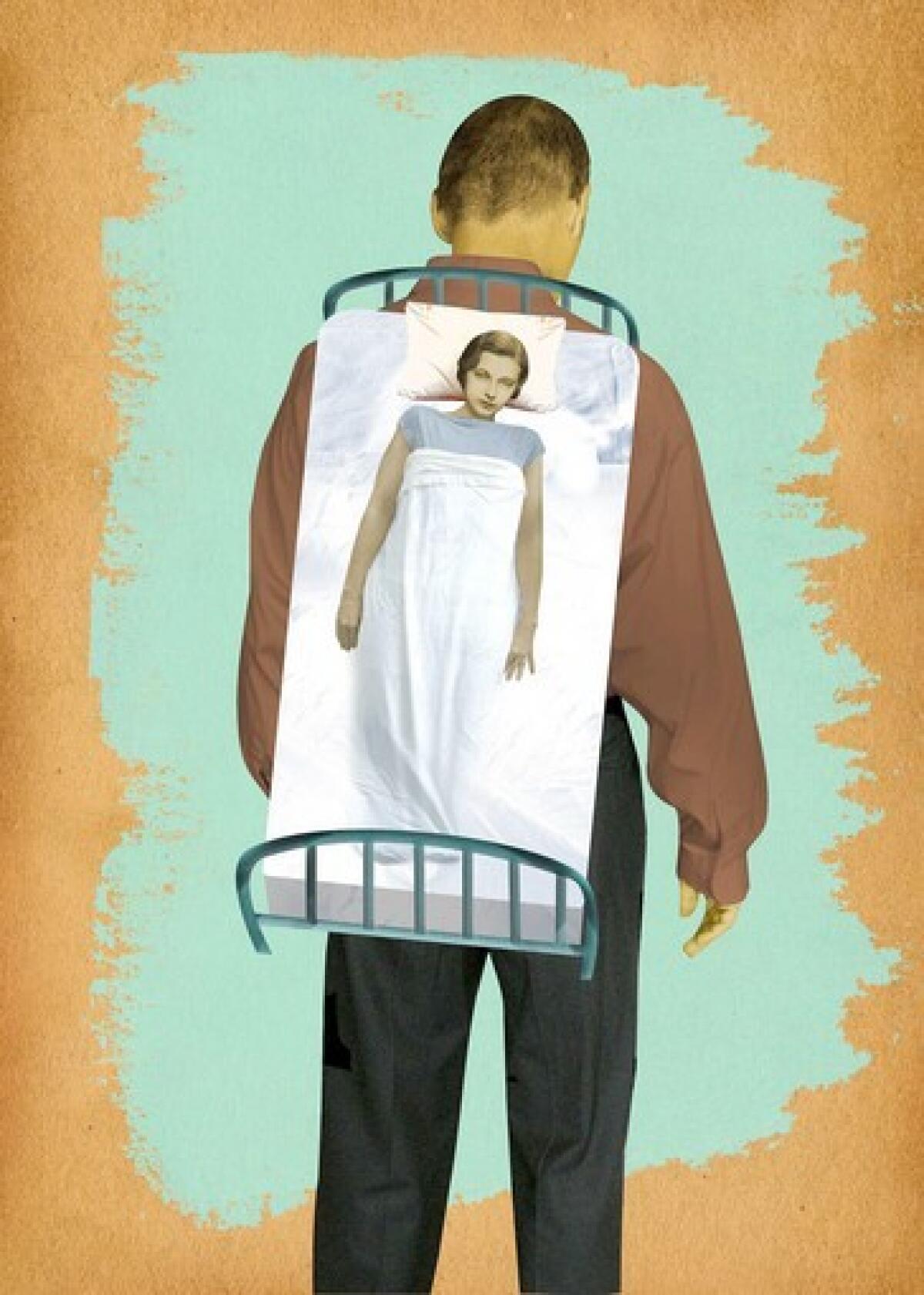

So much for that. Shep’s wife, Glynis, a glamorous but underachieving metalsmith with a tongue as sharp as an asp’s, calmly announces she has cancer. Which means she needs his health insurance; which means he can’t quit his miserable job at the construction company he once owned; which means he must unpack and return to being good old stoic Shep.

A cast of devilishly drawn relatives, almost all of them consumed by rage at their failing bodies, and friends who find excuses not to visit stand ready to stretch Shep’s resources to the breaking point. His best friend, Jackson, is a ranting anarchist who divides the world into Mugs (who “had no guts, and lacked imagination . . . [h]aving never undergone proper adolescent rebellion”) and Mooches (everyone from government contractors to accountants to welfare recipients). Jackson’s teenage daughter, Flicka (a Park Slope name if ever there was), is dying of a rare disease. Shep’s father too is ailing, and he supports his sister Beryl, a kvetchy “filmmaker” who hasn’t worked in years. And that’s not counting the plastic surgery and suicide.

Shriver is drawn to topical catastrophe. Her breakthrough novel, “We Need to Talk About Kevin,” written in the voice of a woman who can’t summon maternal love for her teenage son (an incarcerated campus killer), won the 2005 Orange Prize for female writers. Careening giddily among realism, horror and farce, “So Much for That,” is an angry black comedy about the heartlessness of (could it be more timely?) the American healthcare system. Shriver, who writes in precise, dynamic prose that reads almost like literary journalism, can be heartlesstoo, and sometimes her forthright dialogue tips over into cheap shock tactics. Flicka sounds “like Stephen Hawking after a bottle of Wild Turkey,” and in the heat of an often hilarious one-upmanship contest with the girl over who gets the most toxic treatments, Glynis spits out: “I mean, we’re all obediently mainlining hemlock, docile as sheep, like Jews lining up for the showers.”

Still, if anyone’s going to perk up the often-limp niceness of the women’s novel it’s Shriver, who has no use for earth mothers or noble victims. Glynis has always been an unrepentant shrew(along with her knockout figure, it’s one thing her spouse loves about her), and the sicker she gets, the more recalcitrant and outspoken she grows, like the defiantly unsentimental mother in “We Need to Talk About Kevin.” With good reason: Glynis’ doctors assault her with treatments that make her sicker and more miserable for the purpose of extending her life for a few months, while they and the drug and insurance companies pocket their millions.

Chapters are prefaced with a record of Shep’s dwindling savings. Stirred at last to anger and action, Shep tells Glynis’ confounded doctor that continuing a treatment that’s worse than the disease “is not my wife’s decision if she’s not the one who’s going to pay for it” -- a declaration all the more shattering from the mouth of the uxorious Shep.

It’s possible to read “So Much for That” as a critique of the American obsession with amelioration, by an American who has lived much of her adult life in Britain, a full-service welfare state underpinned by a fatalistic national temperament.

In the teeth of all that suffering and institutional robbery, she prescribes recklessness, whimsy and above all the pursuit of pleasure, leavened with the perverse delight in fleecing those who fleeced you. Thus does shepherd become knacker -- the denouement of “So Much for That” hovers around the implausible. But page for crazy page, the climax offers more fun, vengeful satisfaction and pure tenderness than any treatise on the future of healthcare.

Taylor is a freelance writer in Los Angeles.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.