Coppola’s South American way

While the Cannes official selection kicked off last week with “Up,” the tale of an old man seeking new pastures, the Directors’ Fortnight, a parallel event that takes place at the other end of the Croisette, got underway with a film that marked the creative renewal of an old-timer, Francis Ford Coppola.

A two-time winner of the Palme d’Or (for “The Conversation” and “Apocalypse Now”), Coppola, 70, is back on the Riviera with “Tetro.” Billed as semiautobiography, this Buenos Aires-set family melodrama had been considered a shoo-in for the festival. But Cannes programmers denied it a competition slot, instead offering to show the film as a special presentation. Coppola declined, and accepted an invitation from the Directors’ Fortnight, a Cannes offshoot with a reputation as a showcase for emerging directors and challenging work.

“Tetro” is clearly the work of an engaged and rejuvenated artist but it is not exactly a young man’s film. If anything, it has an almost classical grandeur. Filmed in widescreen, high-definition video and mostly in black-and-white (with a few Expressionist splashes of color), the movie is a sweeping, deeply felt exploration of what one of its characters calls “ancient themes”: sibling rivalries, Oedipal conflicts, the gravitational pull of the family.

“It’s almost like Pirandello,” Coppola said, speaking the morning after the premiere last week. “At the root of the family is a terrible incident that has warped everything. Or in Tennessee Williams, where some trauma has become the secret.”

“Tetro” begins with the arrival of a teenager (newcomer Alden Ehrenreich) in Buenos Aires, and his uneasy reunion with his older brother (Vincent Gallo), who left for a “writing sabbatical” years ago. Both siblings exist in the long shadow of their tyrannical father, a renowned conductor, who had a complicated relationship with his own brother, also a musician (Klaus Maria Brandauer plays both roles).

Personal style

In his first original screenplay since 1974’s “The Conversation,” Coppola incorporated a few elements from his own life: his father, Carmine, was a composer, and his uncle, Anton, an opera conductor. But he cautions against drawing literal correspondences: “Nothing in this movie ever really happened but it’s all true.”

“Tetro” continues in earnest the project Coppola began two years ago with the ambitious literary adaptation “Youth Without Youth,” a long-delayed shift to personal filmmaking, a career path he had envisioned all along. “The Godfather” (in 1972) “was way more successful than I was prepared for,” he said. “You have to learn to navigate those woods.”

Thanks to his successful Napa winery, Coppola has been able to self-finance his last two films, freeing him from the American moviemaking system that he likened to “this cinema gulag.” “It’s as if some executive decided that black-and-white films we’ll pay half for, and we won’t have subtitled films, and all of a sudden that’s the law. It’s like the dictatorship of Stalin telling Shostakovich what music was.”

He considered setting “Tetro” in Detroit, where he was born, but settled on Argentina as a location that made narrative and economic sense. “I needed a country where there was a big cultural tradition and where I wouldn’t get killed by the euro or the pound.”

Coppola immersed himself in the culture, learning the language and hiring locals as collaborators. “Tetro” also taps into a rich vein of 20th century Latin American literature, which Coppola called “the most important movement in fiction in the last 60 years.” The movie feels as old-fashioned as a Greek myth, but with its use of meta-fictional devices and its evocation of a heady bohemian milieu, it also glancingly recalls the work of such modern writers as Julio Cortazar and Roberto Bolano. One of the characters, a literary critic named Alone, is based on a character named Farewell in Bolano’s novel “By Night in Chile” (in turn based on an actual Chilean critic named Alone).

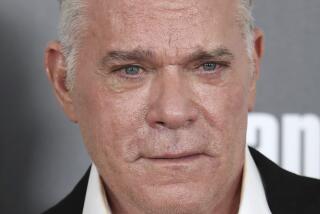

Like the great Coppola films of the ‘70s, “Tetro” is a terrific actors’ showcase. Gallo, not known as an easy collaborator, gives a magnetic performance. “Everyone told me, don’t get involved with him, he’s a nightmare,” Coppola said. “But he’s very bright, very humble.”

The actor, who has been notoriously fastidious with every aspect of the movies he has directed, spoke admiringly of Coppola’s hands-on approach. (Coppola is releasing the film himself in the States, on June 11, his father’s birthday.) “Making a film is so challenging that the idea of not having total control makes no sense to me,” Gallo said.

Salinger text

Ehrenreich, who was 17 when “Tetro” was shot (he’s now 19), had never before appeared in a feature. For his audition, Coppola asked him to read from “The Catcher in the Rye,” a book with enormous personal significance. In his teens, Coppola ran away from military school (as did Ehrenreich’s character) and stopped off in New York City on the way home. “I told my brother all the things I did, and he said, here, read this book, and it was ‘Catcher in the Rye.’ ”

“The reason I make personal films is you can learn something,” Coppola said. With “Tetro,” his big revelation had to do with his brother, August, who’s the father of Nicolas Cage. “I never knew that I felt he abandoned me,” Coppola said, “and it was over something mundane.”

Because the brothers went to different schools as teenagers, he said, “he vanished from my life, which is what I realized when I wrote the story. Now I don’t need to go back there again, which is liberating. That’s the purpose of writing. I can write something else now.”

--

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.