His Oprah moment

That Cormac McCarthy received the 2006 Pulitzer Prize for his most recent novel, “The Road,” was no surprise: He had been previously awarded top honors by the National Book Critics Circle and the National Book Awards for his 1992 novel, “All the Pretty Horses.” What did surprise the literary world was that Oprah Winfrey picked “The Road” as her most recent Oprah’s Book Club choice.

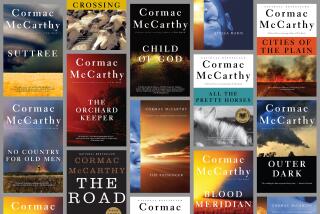

McCarthy, who will appear Tuesday on Winfrey’s show in a rare interview, is considered an American literary giant by critics and readers, his books (notably “Blood Meridian” and “Suttree”) taught in college courses alongside the works of Ernest Hemingway, William Faulkner, Edgar Allan Poe and Mark Twain. The literary establishment was surprised at Winfrey’s choice because it views her selections as lowbrow and repeating a familiar formula: Victim overcomes adversity, dignity prevails over evil, the underdog overcomes overwhelming odds and triumphs in a small but morally significant way. Oprah books have become a cliche, at least among the folks who think themselves her betters. The literary establishment believes that if Winfrey likes a book by a living writer, that writer must be awful. That’s why Jonathan Franzen didn’t want to appear on Oprah’s show when she chose his novel “The Corrections.”

The problem with this attitude is the misguided presumption that Winfrey is predisposed toward “happy” books at the expense of “literature.” This is not necessarily the case. What she seems to prefer are moral books, and this is why she tends to overlook so many “literary” authors. American literary authors have all but abandoned the general reading public, noses upturned. To Winfrey, though, an author’s literary style, erudition or linguistic experimentation is of secondary importance: She’s primarily concerned with the social aspects of literature, how literature can help our culture. If the work doesn’t have a useful moral foundation that has the potential to make the world a more civil and pleasant place, it’s not going to be one of her selections.

What often passes for high “literature” today is writing that is impenetrable and onanistic: self-enclosed systems of game-playing that only the author and a small band of professors and masochistic devotees understand (or claim to understand). Of course Winfrey would never pick William Gass’ “masterpiece” doorstop of a novel “The Tunnel.” Why should she? Who can read it? And Thomas Pynchon? He might be smarter than the rest of us mortals, but that doesn’t mean he’s communicating anything to us other than the unpleasant reality that he can’t seem to stop writing volumes of brilliant gibberish, and the world will be none the worse when John Barth’s books are all out of print.

Even McCarthy has fallen prey to the allure of putting difficult prose style before the story he is telling. His fourth novel, “Suttree,” for instance, is a brilliantly written book that tells the episodic story of a man’s derelict life in Knoxville, Tenn., where McCarthy was raised (born in 1933 in Rhode Island, he and his family moved to Knoxville when he was 4). Great though the novel may be, without a dictionary nearby and a little imagination -- since McCarthy sprinkles the book with neologisms -- no casual reader stands a chance. His early books shoved average readers away as the young author tried to one-up his primary literary influence, the extremely difficult Faulkner.

During those years, McCarthy lived a bare, reclusive life, often holed up in cheap motels with his typewriter, the cliche of the starving artist. He has rarely granted interviews, which makes his appearance on “Oprah” all the more startling. While many authors keep themselves continually in the public eye giving readings, making statements to the press, going on the lecture circuit and teaching at universities, McCarthy keeps to himself. Writing, for McCarthy, is not a spectator sport. Writing is a solitary enterprise, and he has guarded his solitude with ferocity, often at the expense of comforts most people would consider baseline necessities of life.

Starving artist

Now in his 70s, McCarthy is married to Jennifer Winkley, his third wife, and they have a young son together (he also has a son by his first marriage). His first two wives didn’t have the comforts that McCarthy makes available to his current family, thanks to the awards and success of recent years. His second wife, Annie DeLisle, experienced first-hand what it’s like to be the wife of a serious artist who’s more dedicated to his work than to her. In a 1992 interview she described how the couple often lived in near poverty even though McCarthy received lucrative offers to discuss his work at universities. He’d turn these down, she said, because he felt he had said enough about his books in the works themselves. McCarthy did receive some grants -- most notably Guggenheim and MacArthur fellowships -- that helped along the way.

What makes Winfrey’s choice of McCarthy most surprising is not McCarthy’s stubborn and commendable aversion to self-promotion and not the literary bent of McCarthy’s work but the apparent bleakness of the novel. “The Road” is the story of a father and son trudging through the ash of a nuclear winter toward nothing in particular. Horrific though “The Road” may be, barren and gray, just because a novel is bleak does not mean it isn’t moral. The more bleak a work of art is, the more hopeful it may actually be -- serving as a caution, a warning that we’d better shape up.

The moral

McCarthy seems to have taken his cue from Ernest Hemingway. In his 1958 Paris Review interview, Hemingway, talking about “The Old Man and the Sea,” said, “I had a good man and a good boy and lately writers have forgotten there still are such things.” Some might say the ending of “The Road” gives a glimmer of hope, but a sober look at the book’s conclusion betrays such optimism. The world is dead, and the few survivors, at least on the continent McCarthy describes, are not going to last long. All humanity can hope for in “The Road” is a pleasant moment or two before the inevitable.

In a 1985 interview, Nobel laureate British playwright Harold Pinter said, “There’s no point, it’s hopeless. That’s my view. I believe that there’s no chance of the world coming to other than a very grisly end in twenty-five years at the outside.” McCarthy seems to agree, but with qualifications. McCarthy believes that so long as humanity exists, even if that existence is tenuous, atrophied and horrific, so too will man’s capacity for love and dignity.

McCarthy doesn’t kid himself, or his readers, for that matter: violence and power hold dominion over our natural history. But woven through that history are also our better qualities, qualities that will not be eliminated unless our species becomes extinct. This message explains why Winfrey chose “The Road” for her book club. Though the novel is bleak, McCarthy believes in the human capacity for goodness in a violent world. He just happens to be a great writer as well.

*

Eric Miles Williamson edits American Book Review and is a member of the board of directors of the National Book Critics Circle. He wrote “East Bay Grease,” “The Two-Up” and the forthcoming “Oakland, Jack London, and Me.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.