Mr. Happy

TWO lessons learned during the filming of the new Jim Carrey movie: 1) Elaborate faux tattoos are a big turn-on for women; just ask co-star Virginia Madsen. 2) Carrey’s fixation with the number 23 has led him to believe that “the universe is tapping me on the shoulder and saying, ‘There’s some kind of intelligence or something beyond coincidence in the world.’ ”

Oh, and he’s also figured out the meaning of happiness. “I wanted to find out what makes people happy,” says Carrey, seated on a cushioned bench on a brick balcony that juts off the sixth floor of his Brentwood production office, wearing a black leather jacket, blue-and-black Where’s Waldo striped shirt and black jeans. “I thought it was just making them laugh. And that’s a fantastic thing, because that does give them temporary freedom from themselves.

“But it’s not the answer. The cure is people realizing who they are and that there’s nothing they can do on the earth or nothing that can happen here that will add to them or take away from them at all. You need to just relax.”

Which sounds like just the kind of mantra that would be impossible to reconcile with a career in Hollywood. “Maybe I haven’t,” Carrey says and laughs, rocking back a bit. “Just hang out for another year until I become America’s joke. You risk that when you tell the truth about yourself.”

The truth, coming to the surface, is how Carrey summarizes the thematic force of his new movie, “The Number 23,” a paranoid thriller with dark echoes of “Memento” and “The Omen.”

But he also knows now, in a way that he’s been striving to understand for most of his 45 years, that facing his own truths, however scary or ugly, has been the essential struggle of his life.

“Nothing I do in this world will be who I am. I believe we’re something entirely different,” Carrey says with the rushing conviction of someone who on some level is also trying to convince himself. “We’re here to witness it and to play with form. What can I make out of the Lego set of life? Can I make something fun out of this? It’s all about being happy, man.”

He’s just returned from the Super Bowl in Miami with girlfriend Jenny McCarthy (a severely disappointed Chicago native), and he’s recently grown his hair out. The cool wind wisps it across the etched contours of his face, an intriguing map of vulnerability and ambition. Rather than retreating inward or dissolving into a character, as he has done so memorably onscreen, in person Carrey is living right up against the very edge of his skin. Despite his stillness, he almost seems as if he’s vibrating.

The actor’s latest movie, “Number 23,” unfolds as a mystery pursued by Walter Sparrow (Carrey), who is given a novel by his wife, Agatha, (Virginia Madsen) and begins to see himself in its tortured protagonist, an obsessive and self-destructive detective named Fingerling (also Carrey). As the novel begins to read more like a confession, Sparrow’s mental moorings unravel in the murk of his past and the bizarre recurrence of the number 23 in his life.

The 23 Enigma, as it’s sometimes called, is a form of apophenia, or the seeing of patterns or connections in random information (a phenomenon that some have suggested is a link between psychosis and creativity). A Canadian friend introduced Carrey to the 23 enigma a dozen years ago, by pointing out license plates, historical facts and sports statistics that played into its numerical “mind virus.”

The movie, of course, comes out today, Feb. 23.

“To me, it’s some little game you play with the universe,” says Carrey, who years ago changed the name of his production company from Pit Bull Productions to JC 23 Entertainment because of his 23 fixation and a personal connection to Psalm 23 (“It would symbolize for me making fearless choices,” he says). “Maybe there is something magical about it.”

Everyone got involved in the game during filming, including Madsen’s son Jack and Carrey’s 19-year-old daughter, Jane, who told her father at one point that she had gotten a “23” tattooed on her arm. “I reacted really badly to it,” Carrey says and laughs at himself, shaking his head. “Totally the dad thing.”

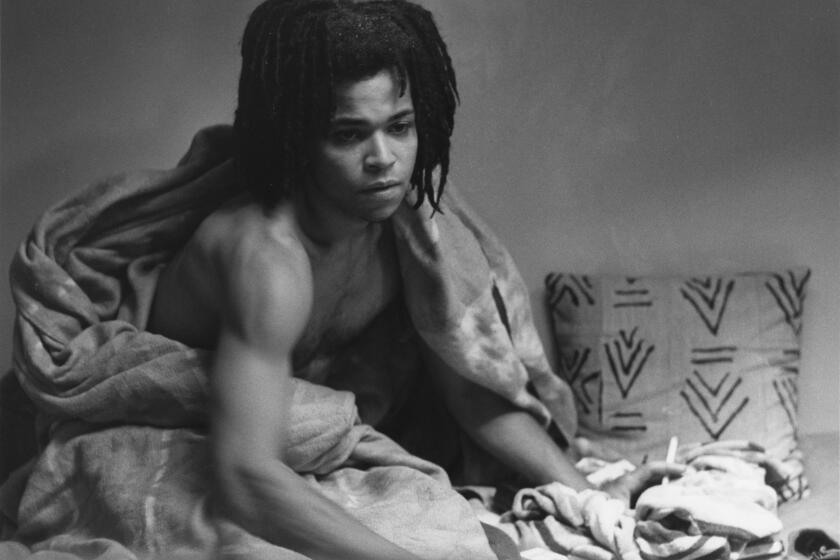

Carrey sports his own disturbing body ink in the film.

The night before his first day filming as Fingerling, Carrey stayed up all night with Oscar-winning make-up artist Billy Corso (“Lemony Snicket’s A Series of Unfortunate Events”) digitally designing a complex tattoo that Corso painted onto Carrey’s back.

Carrey took off his shirt in front of director Joel Schumacher the next morning to reveal a skeletal tattoo that clung to the back of his shoulders and snaked down his spine.

According to Carrey, this did not go unnoticed by the female members of the cast and crew.

“Oh my God -- that’s when my professional admiration of Jim flew out the window, and I had a huge crush on him,” Madsen says. “Because then he looked like the violent punk rock dude, you know? And I just happen to have a thing for tattoos. But he was not a single man. I could not make a play,” she says and laughs.

Madsen, who also plays a dual role as Fingerling’s femme fatale Fabrizia, says: “He’s a very intense guy, Jim. He burns real hot. So when he walks into a room you can sense him. There are people like that in the world. Sometimes we call it star quality, sometimes we call it alpha dog. But he’s got this electricity about him. Perhaps he just runs on a low frequency -- you know it’s there but you can’t see it or hear it. It unnerves some people. And it takes some people a while to adapt to that frequency.”

That extrasensory intensity was born out of the crucible of his economically sparse childhood outside Toronto, where for a time the family lived in a camper and Carrey felt compelled to entertain.

“I’ve been looking for answers my whole life,” says Carrey, the youngest of four children. “Since I was a little kid, I was like two people. One of them was out in the living room trying to make everybody happy. I had a sick mom, so I was always trying to make her laugh. I actually remember having the thought when I was about 7 or 8 years old that I wanted to prove to her that her life was worth something because she gave birth to a miracle person. So that was my goal, to become that. It made me strong, but it took a little bit of the childhood thing away.

“The other half of me was in my bedroom with a legal pad trying to figure out the universe, trying to define it,” he says. “And I’ve figured a lot out. I’m in a really good place. It’s a lot simpler than I thought it was.”

Carrey’s begun thinking about trying to share this newfound “awakening” with others in a book tentatively titled, “Be Ready to Be OK,” which he describes as his “thoughts about the universe.”

All his observations about human behavior that have no place in screenplays or comedy routines or talk show bits will funnel into this new repository of earned wisdom.

But he’s well aware of the pitfalls of talking about his inner life. “There’s always a little bit of fear involved because of how people are going to interpret what you say, “ he says. “That can be dangerous territory when you feel like you’ve got some spiritual answers, because you don’t want to come off like a nut. But if you do, so be it.”

In the last few years he has engaged in new means of self-expression, such as ice skating and painting, which he does in the half of his living room that he’s devoted to a studio where he can work on his conceptual art.

“I’m finding all these wonderful things in my life lately that are outside the business, that don’t have to become a commodity, that make me feel like a child when I do them.”

“This is the happiest I’ve ever seen him,” says Schumacher, who has known Carrey since the early ‘80s and directed him as the Riddler in “Batman Forever.” “Jim was always fighting off demons but struggling toward the light.”

Carrey talks a lot about freedom, and when taken with his recent efforts to feel like a child again, it’s not hard to see that the pressure he felt as a kid got transferred into the ambition of his working life, that need to entertain, to keep everybody laughing. As if that could erase the painful aspects of their lives -- or his. “When you’re a poor kid from nowhere -- speaking as a poor kid from nowhere myself -- it’s hard to shut off the machine,” Schumacher says. “You’re driven. You work hard. You’re ambitious. And then you get your dream and it’s bigger than you dreamed it. And then, ‘Well, now who am I? Because I don’t know how to be this person.’ ”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.