‘Rocky’ road paves path to Iraq drama

ON the back wall of Irwin Winkler’s office at his home in Beverly Hills is a framed copy of Vincent Canby’s New York Times review of “Rocky,” which Winkler and his partner Robert Chartoff produced 30 years ago. According to Canby, then one of the country’s most influential critics, “Rocky” was a “sentimental little slum movie” whose star, Sylvester Stallone, was so terrible that his performance reminded the critic of “Rodney Dangerfield doing a nightclub monologue.”

Of course, right next to the review, perched on the mantelpiece, is the Academy Award “Rocky” won for best picture.

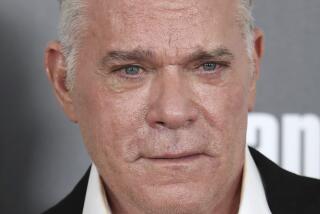

Having made movies for nearly 40 years, first as a producer and more recently as a director, Winkler knows all too well how capricious the movie gods can be, crushing dreams in one breath, bestowing bouquets with the next.

Full of energy at 75, when many of his peers have retired, Winkler has had quite a career, making his first movie with Elvis, his most recent one with 50 Cent. Along the way as a producer he’s had five best picture nominations, plenty of hits and made a string of classic films with Martin Scorsese, including “Raging Bull” and “GoodFellas.” He’s even survived painful failures, notably “The Right Stuff,” a critically beloved 1983 film that remains a joy to watch, even if it flopped at the box office and lost to “Terms of Endearment” at the Oscars. Not wanting to endure a round of condolences that night, Winkler put his wife and kids into a white limousine and took them to eat at Fatburger instead.

In Hollywood, even victory can be bittersweet. When “Rocky” won best picture from the Los Angeles Film Critics Assn., sharing the award with “Network,” Winkler sought out Paddy Chayefsky, “Network’s” fabled screenwriter, to congratulate him. “He wasn’t happy for me,” Winkler recalled. “He just thought, ‘What am I doing, sharing an award with this ... ?’ ”

Though he hasn’t abandoned his producing career (he’s an executive producer on “Rocky Balboa”), Winkler has focused on directing films in recent years, working with actors such as Robert De Niro and Kevin Kline. His new film, “Home of the Brave,” which opens Friday, is one of the first feature films to show the ravages of the war in Iraq. The film, which stars Samuel L. Jackson, Jessica Biel and 50 Cent, follows the lives of a group of soldiers as they try to survive the end of their tour of duty and make the transition to life back home.

Winkler said the idea for the film came from watching a news show about Iraq veterans having difficulty making the adjustment. “They talked about the parties people would throw for them, but I kept thinking, ‘What happens when the party is over?’ ”

Many soldiers had a difficult time talking about their experiences, in part because while they went to Iraq on an idealistic mission, they were greeted as occupiers, not liberators. “You never knew if you would be greeted warmly, spit on or shot at,” Winkler says. “The soldiers who came home never wanted to talk about it, because who’s going to understand how they felt?”

The movie ends with a quote from Machiavelli: “Wars begin where you will, but do not end where you please.” For Winkler, it’s an admonition that applies to all kinds of misguided conflicts. “Everyone in the Bush administration clearly thought, ‘Oh, we’ll knock out these guys in a few weeks and be outta there,’ ” he says. “You could say the same thing about the Israelis counter-attacking against Hezbollah. Or the Japanese in World War II. Did they know when they attacked Pearl Harbor that they’d end up with an atom bomb in their lap? If you start something, you better know where it’s going to end.”

After Mark Friedman wrote “Home of the Brave,” Winkler “schlepped” the project around town, getting a polite no wherever he went. Even though his pals include such power brokers as Mort Zuckerman and Universal chief Ron Meyer, who gave him a movie replica of a Los Angeles police car to park in his driveway to discourage burglars, Winkler knows that friendship doesn’t finance movies. “Everyone said, ‘It’s a drama. It’s about the war. Who’s going to see it?’ And maybe they’re right. Studio heads all tell me they don’t make dramas. They’re in the tent-pole business.”

Having coaxed Jackson into playing a major role, Winkler took the project to Avi Lerner, an indefatigable producer who generally makes low-budget action movies but occasionally takes a shot on more sophisticated fare. Knowing he could use Jackson to help sell the foreign rights, Lerner agreed to bankroll the film while Winkler got MGM to provide U.S. distribution. Shot in 35 days, the film cost roughly $12 million, with Winkler taking no salary and the actors working for reduced fees.

Lerner is famous for not reading scripts. Winkler isn’t sure that’s such a bad thing. “I don’t think Louis B. Mayer read them either. Someone would tell him the story and he either got it or he didn’t. Working with Avi reminded me of back when I was doing pictures for Arthur Krim at United Artists. He felt, if I trust you enough to give you $10 million to go off and make a movie, then I trust you enough to leave you alone.”

Winkler has been involved in almost every imaginable part of show business. After graduating from New York University in the 1950s, he toiled in the William Morris mailroom with the likes of Bernie Brillstein and Jerry Weintraub. They were sharp operators; Winkler was not. “I was lousy, totally in over my head,” he recalls.

He quit, joined up with Chartoff and became a music manager, representing the likes of Joni Mitchell and Buffalo Springfield. When someone at MGM asked Winkler if he wanted to produce movies, he jumped at the chance. His first film, “Double Trouble,” was an Elvis vehicle directed by Norman Taurog, who’d been making comedy shorts back in 1919.

“I was very impressed by Mr. Taurog,” Winkler recalls. “When we had dinner on a night shoot, he had someone bring out a table with linen and silverware and a red rose.” As for Elvis, “when he’d leave the lot, a couple of his guys would cover him with a blanket so he wouldn’t see the crowds of people waiting outside the gate, waiting to rush the car.” Winkler shrugs. “But there were no crowds. No one cared, but no one wanted Elvis to know, so he went out every day under a blanket.”

Winkler and Chartoff had a critical hit with “They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?” followed by box-office successes starring the likes of Barbra Streisand and Charles Bronson. His friendship with De Niro dates back to 1971, when he was casting “The Gang That Couldn’t Shoot Straight,” a mob comedy that was supposed to star a young up-and-comer named Al Pacino. Just before shooting was to start, Pacino got a better offer, to be in “The Godfather.”

His replacement was De Niro, a shy, skinny unknown who was already such a perfectionist that, despite playing a largely comic role, he insisted on going to Italy to research the part. “I told Bob we didn’t have the money to send him,” Winkler recalls. “And he said, ‘That’s OK, I’ll pay my own way.’ ”

As a producer, Winkler learned to leverage his success. It would be easy to criticize him for helping turn “Rocky” into a never-ending series of sequels, but he says the money the movies made gave him the clout to do more ambitious projects with such filmmakers as Scorsese, Bertrand Tavernier, Costa-Gavras and Phil Kaufman.

“Having that franchise allowed us to go into UA and say, ‘OK, you want another “Rocky”? Fine, but we want to do “Raging Bull” too.’ It helped that when we walked into their offices, that they saw dollar signs. That’s how the business works.”

Winkler began his directing career in 1991 with “Guilty by Suspicion,” which starred De Niro as a blacklisted Hollywood director at the height of the Red Scare. “I just wanted to do it,” he explains. “I was reading the original script where De Niro’s character is called before HUAC and told to either name names or lose his career, and I thought, ‘What would I do?’ ... And thinking about what I might do -- and why -- made me realize I really had to do the film myself.”

Winkler has had a mixed track record as a director, but you can’t say his films have ever stooped to conquer. He’s still looking for projects that have something to say. When I asked him the best lesson he had learned about directing, Winkler recalled the time when Scorsese was shooting a scene in “New York, New York” in which De Niro’s character proposes to Liza Minnelli’s Francine. It was a long day, the production was behind schedule and Winkler was badgering Scorsese to move on.

“I told Marty, ‘Come on, you’ve done 21 takes. We gotta get out of here.’ And Marty said, ‘Yeah, but in that last take, I think I saw a tear in Liza’s eye. We could stop, but don’t you want to get that tear?’ ” Winkler laughs. “Of course, he was right. You have to go for the emotion. So I said, ‘OK, OK, Marty, let’s keep going.’ ”

*

“The Big Picture” runs each Tuesday in Calendar. If you have questions or criticism, e-mail them to patrick.goldstein@latimes.com.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.