All in his head

IT’S at least 104 degrees in the shade in the foothills outside Lancaster. Anthony Hopkins is nursing a ruptured Achilles’ tendon and limps toward a tiny patch of cover from the sun, blinding dirt swirling all around him. In between setups for his new movie “Slipstream,” Hopkins can’t retreat to a cushy, double-wide Starwaggon -- the low-budget production can’t afford it -- and when production wraps for the night, he’ll crash not in a Four Seasons but a nearby Comfort Inn.

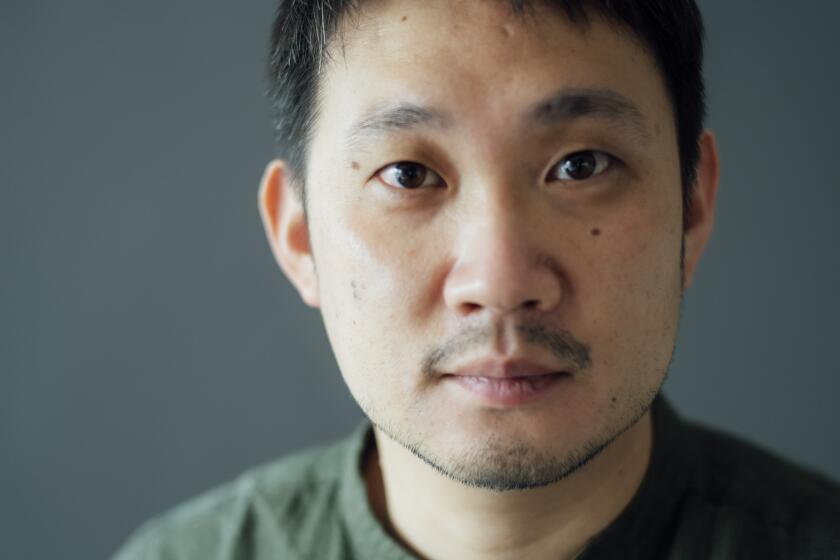

Does the Oscar winner for best actor for 1991’s “The Silence of the Lambs” really deserve this? He says he actually needs it.

Even though the 69-year-old actor can command $10 million and more to star in some splashy Hollywood role, Hopkins says he’d much rather be doing exactly what he’s doing on this miserably hot July day: making his very own indie movie.

“I love this because it’s punishing,” he says, gulping down some water as cinematographer Dante Spinotti blows sand out of a camera lens. “I love the heat, the abrasiveness of it all. I love the difficulty and the hardship. It keeps me on my toes.”

“Slipstream,” which premieres Saturday in the edgy New Frontier section at the Sundance Film Festival, is Hopkins’ film in every conceivable way.

He wrote it, directed it and stars in it alongside his wife, Stella Arroyave. As if that were not enough, Hopkins also composed the “Slipstream” score and conducted its orchestra. But perhaps his greatest “Slipstream” challenge lies in trying to elucidate what the film has to say.

A fast-twitch journey into a screenwriter’s consciousness, “Slipstream” unfolds in both the blink of an eye and across 110 nerve-jangling minutes. Birds -- and spiders -- talk. Performers change costumes in the middle of scenes, cars switch colors, characters transform into the actors playing them. A quick clip of Richard Nixon flashes in one scene, followed by a snippet of “Invasion of the Body Snatchers” in another, then a few shots of Adolf Hitler in the next. For seemingly no apparent reason, a Frisbee flies through the frame. And the movie is all tied together by a conceit reminiscent of “Jacob’s Ladder.”

“I’ve always been interested by the mind and the dream world,” Hopkins says a few days after he has emerged from weeks in the “Slipstream” editing room. “I’m intrigued by the peculiar structure of dreams and the odd things that happen in our everyday lives.”

Odd things, indeed.

‘Don’t ask why’

IT can’t be all that easy to take direction from Hopkins.

His manner on the high desert set is patient and generous, but when he gives actor Gavin Grazer (yes, he’s the producer’s younger brother) a line reading, Hopkins is so good it just doesn’t seem fair.

“I’ve worked with a lot of people who are control freaks,” Hopkins says after getting Grazer’s scene in just a few takes. “That takes the fun out of life, the joy out of acting.”

As dicey as it might be for actors to hear the perfectly intoned Hopkins speak their dialogue, it’s equally challenging to understand how the movie is going to come together.

“One or two of the actors couldn’t get it,” Hopkins says, declining to name names. “And I couldn’t explain it to them. I said, ‘Don’t ask why. It’s just the way it is.’ ”

At the center of Hopkins’ story is a writer named Felix Bonhoeffer (Hopkins). The scribe isn’t certain what’s happening in his life, and neither, for that matter, is the audience.

It appears Bonhoeffer has been summoned to the set of an out-of-control film; its director (Grazer) is losing his grip, and the film’s star (Christian Slater) has suffered a breakdown. A third-rate producer named Harvey Brickman (patterned after the colorful Joseph E. Levine and played by John Turturro) also has rolled into town, and, while barking into his mobile phone, randomly says that Hopkins doesn’t deserve more money for another “Hannibal” sequel.

It’s a movie, of course, but is the movie inside the movie real? Or just a rapidly firing neuron in Bonhoeffer’s imagination?

“It’s about a guy who’s plunged into limbo,” Hopkins says. “He doesn’t know who the hell he is. Space and time are all twisted. It’s a jumble.”

Movie’s genesis

“SLIPSTREAM” began as a lark.

“I only wrote it for fun,” says Hopkins, who previously had directed the 1996 Anton Chekhov adaptation “August” and the 1990 television movie “Dylan Thomas: Return Journey.” “I had no idea where it was going. It just kept evolving on itself. I always wanted to poke fun at the movie business and the acting profession -- they take themselves so seriously. I wanted to poke them in the nose. And what were people going to do? Arrest me if it wasn’t any good?”

At first, Hopkins shopped his script to the studios for whom he had made so much money as an actor.

They politely expressed interest but then started offering script notes and casting ideas. Hopkins wasn’t interested in the input. He sent the script to Steven Spielberg, who praised the dialogue but warned, “You’ll have a tough time getting it financed.”

He was right.

One potential backer, Hopkins says, “wanted to take meetings, as you say. They wanted to have final cut. So I kicked them out,” even though he had started filming. A new, unidentified patron was quickly found for the film, which cost less than $10 million to make, and Hopkins says he was left alone to make the movie just as he pictured it in his mind.

But Hopkins and producer Robert Katz come to Sundance without a theatrical distributor attached. “We didn’t want to have individual distributor screenings,” says Katz. “We wanted to show it in a place that we thought would be receptive to Tony’s vision.”

Musical score

IT’S a December afternoon, and 32 musicians have gathered inside a scoring stage at the CBS Studio Center. With composer Harry Gregson-Williams (“The Chronicles of Narnia”) looking over his shoulder, Hopkins composed all 64 minutes of “Slipstream’s” score, performing much of it himself on a synthesizer. But now he’s about to pick up the baton and lead a small orchestra.

With a black T-shirt, blue jeans and long silver hair, he looks the conductor part. But what the filmmaker does next is almost as surreal as his film: the composer-conductor (Hopkins) scores a scene of an actor (Hopkins) whose dialogue was written and whose performance was directed by the man holding the baton. The music builds, and it’s ethereal, haunting, lovely.

“I don’t know what the hell it means,” Hopkins finally says of the film. “But if you do something and don’t care, you do better work. Even in film acting, if you do what you like, free of strictures, it will be better. The film is about letting go.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.