A chance to move beyond Hong Kong

NEW YORK -- Even though we tend to assign fixed identities to the directors from Hollywood’s golden age, the résumés of filmmakers such as Ford, Hawks, Cukor and Wyler actually cover a range of movies.

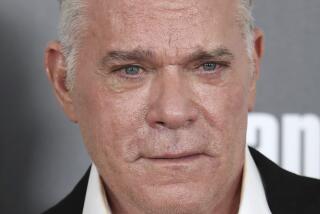

Forty-six films into a nearly 30-year career, Hong Kong filmmaker Johnnie To is one of the few directors whose career shows that kind of versatility. Now 52, To, whose film “Exiled” opens today, began his career in the early ‘70s as a messenger at Hong Kong’s TVB television network, working his way up to production assistant, props man and director of serial dramas before making his first movie, “The Enigmatic Case,” in 1978.

To has long been revered by American fans of Hong Kong filmmaking who have seen his movies on DVD or at film festivals. That’s about to change with the American release of To’s 2006 “Exiled,” which opened in New York last week, in Los Angeles today and in other cities around the country. It’s the widest distribution a Johnnie To film has had in the U.S. Serendipitously, it’s also as fine a piece of genre filmmaking as anyone has made in the last 10 years.

Though he’s known primarily as an action director, within that description can be found martial arts outings, superhero movies (the wonderful “Heroic Trio” and its sequel, “Executioners”), gangster films (“Election” and its sequel “Triad Election”), cop thrillers (“Breaking News,” “PTU”), and one film, the sublime 2004 “Throw Down,” which was made as a tribute to Akira Kurosawa (whom To cites as an influence) but recalls the playfulness and lyricism of Jean-Luc Godard’s “Band of Outsiders.”

“People sometimes see me as an ‘action’ director,” writes To, in an e-mail conversation we conducted between Hong Kong and New York, “but when I conceive how action is staged, I always think about what these set pieces would convey of the emotions of the characters or the mood of a scene.” In “Exiled,” To follows the story of a former hit man, trying to leave his gangster past behind to live peacefully with his wife and child. When his former associates (among them the wonderful actor Anthony Wong), now split into rival teams, are assigned to finish him off, they instead band together and ignore their contract to help their old friend get clear of his past.

Bearing traces of Sam Peckinpah’s “The Wild Bunch,” “Exiled” is simultaneously an exciting and melancholy examination of honor among thieves. “I’m always fascinated by values of friendship, honor and sacrifice,” says To, who claims romantic heroes like his are so appealing precisely because we have nothing like them in our real lives. “You can say their mode of behavior is outdated, but the values they demonstrate transcend time. It’s what audiences, like myself, aspire to.”

At a time when action filmmaking has reached a point where American audiences seem to crave visceral excitement to the exclusion of everything else, To still sees his primary function as that of storyteller. “Films of any genre need storytelling, even if the popularity of CGI [computer-generated imagery] seems to refute that.” Even the most spectacular of his set pieces -- such as the five-man standoff that opens “Exiled,” in which a door is shot off its hinges and appears to somersault in the air as it’s suspended in a crossfire -- are a way of advancing character and emotion. “The scene is interesting not because people are pointing guns at each other,” says To, “but because we as an audience are drawn to the tension and conflict between the characters. I think it is important to see action not simply for action’s sake.”

For To, the restrictions imposed on commercial cinema have been a spur to creativity. When asked if he shares the belief of many American film critics that the popularity of Hong Kong cinema in this country has something to do with the classic style of storytelling Hollywood has largely abandoned, To responds, “Hong Kong cinema, unlike China or Taiwan, is a commercial industry. It’s not supported by art cinema. And filmmaking is a form of personal expression but also a business. It’s crucial to find ways to make the two directions coexist. Therefore, filmmakers here are versatile. Filmmakers here are open to all kinds of possibilities and they receive a degree of creative freedom that their American counterparts would never get. For me, making genre films allows me to experiment with different visual styles and storytelling techniques. They allow me to always challenge myself with something new.”

One of the earmarks of To’s work is his use of Hong Kong at night as a deserted playground swathed in black velvet and neon. In “Throw Down,” a fight spills out of a club in a way that recalls the vast scale of the “Broadway Melody” number from “Singin’ in the Rain.” “Darkness,” says To, “gives me more freedom to play with lighting. Also, because we’re working with a limited budget, darkness can help me to block out things I don’t want to see on the big screen. It’s very much similar to stage lighting design.”

Looking forward, To says he’d like to make a movie about a notorious crime-infested Hong Kong area that existed from the early 1900s until it was torn down in the ‘60s and known as “the Walled City.”

“This was a place where crimes, drugs and the gangs of Hong Kong were born. I hope one day I can use film to dramatize and document this place as it evolved through the turbulent modern history of Hong Kong and China.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.