Brenda Wineapple’s study of Civil War society measures past and present

Near the end of “Ecstatic Nation: Confidence, Crisis, and Compromise, 1848-1877,” Brenda Wineapple’s fresh and riveting account of America at war with itself, she writes of a sense of fatigue that coursed through the nation in the 1870s.

The North had won the war and slavery had ended, but there the gains stalled, leading Quaker poet and abolitionist John Greenleaf Whittier to lament that, between opportunistic carpet-baggers and Confederate vigilantes, the newly freed slaves in the South “had not been saved from suffering,” yet “I see no better course.”

There was also a sense among some that it was time to move on and forget about the past divisions. “The negro will disappear from the field of national politics,” wrote the Nation, a modern liberal beacon then in its infancy. “Henceforth that nation, as a nation, will have nothing to do with him.”

It’s hard in an era of voter suppression efforts in minority neighborhoods, with a Supreme Court that devalues the Civil Rights Act, and when an armed Florida vigilante can spark a confrontation and then claim self-defense, to not measure past against present. Especially given the argument streaming through conservative America that this is a post-racial society in which blacks no longer need special protections from the legal system.

Whites and blacks have a different history in these same United States, and it behooves us to recognize that. And to sense — in the present — the weight of the past. Wineapple’s “Ecstatic Nation” does a laudable job of bringing to life not just the Civil War but the society in which it occurred — and has evolved into the present.

Wide in scope and deep in detail, Wineapple’s book moves with great control from abolitionist Boston to the Lincoln White House to crucial battle sites and then on to the unsettled West. The writing drags a bit here and there, feeling as though Wineapple is presenting a case then backing it up with a chorus of quotes. The result can be a confusing mish-mash of characters and opinions that can take a couple of passes to digest.

But when Wineapple seizes control of the narrative, she does it with hard-to-resist force, as in this summing-up of the still-seething, postwar Southern mind-set:

“Lee had been nobler in defeat than Grant in his victory, Lincoln’s assassin had been indefensible but brave, the Confederates were the finer men and, best of all, the South had abandoned the contest of the last four years only to resume it in a wider arena: in its literature, manners, intellect, refinement, in its very civilization. Defeat was victory, failure the measure of grace, fortitude the hope and watchword of the future. As James Branch Cabell would say, ‘No history is a matter of record; it is a matter of faith.’ ”

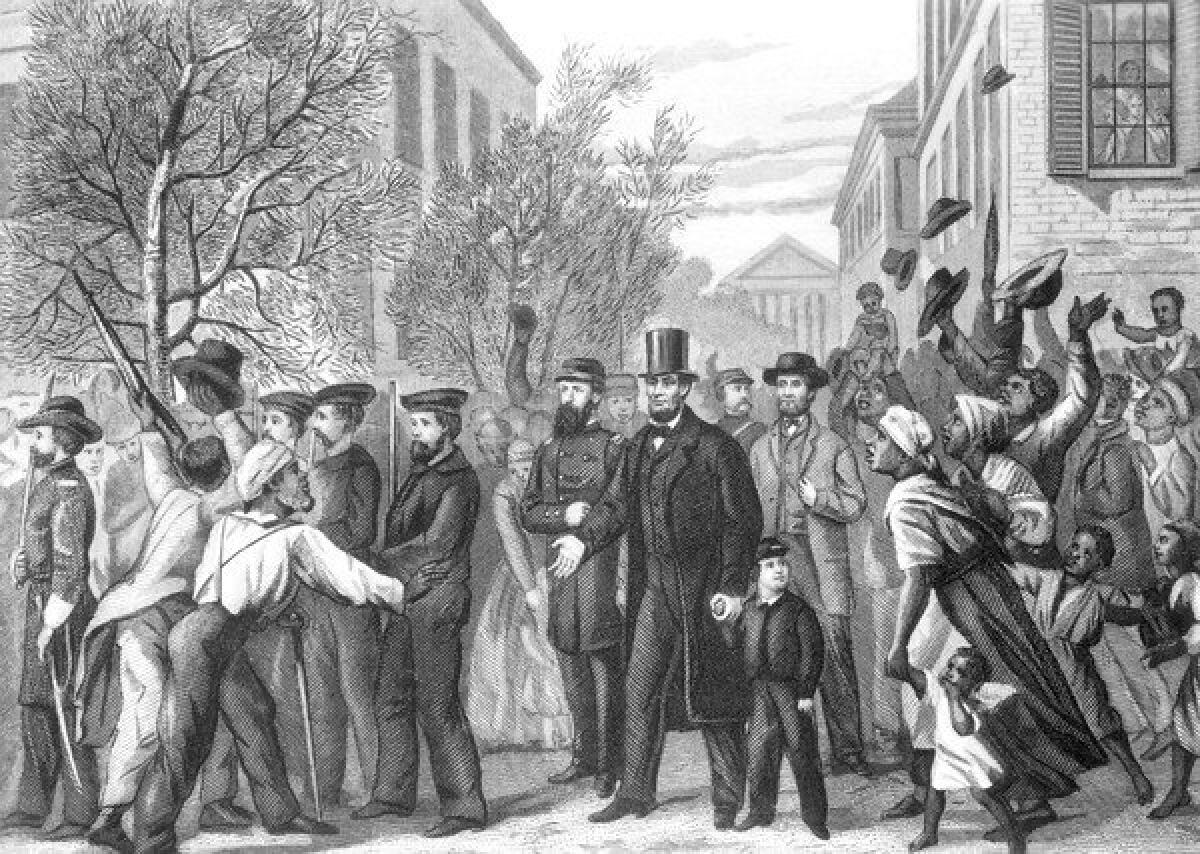

The power of Wineapple’s book lies less with the details of the Civil War, which has its own library of chroniclers, than with her portrayal of life around the fighting. The war came after years of political wrangling and compromises, then shifted, with Lincoln’s 1860 election, to open division. The Southern states began seceding, the rebels fired the first shots on the federal army at Ft. Sumter, and the bloodbath was on.

Wineapple wisely sticks only to the highlights of the war story and focuses instead on the home fronts during the fighting (which filled only four years of the three decades she covers), the politics behind the pro-union forces and the debates over whether current and former slaves should become soldiers. That discussion, as much as the war itself, displayed the sense of white supremacy that guided even some abolitionists. And it weighed heavily on the politics of postwar peace and Reconstruction as well as other rights battles of the era: The brutal subjugation of the native tribes and the fight by suffragists to gain the vote for women.

The Civil War ultimately defined us as a nation of states, not a loose confederation of smaller democracies. Yet it didn’t resolve the definition of a voter, of who was entitled to a political voice. Few of the lines of debate were clean. Some abolitionists opposed extending voting rights to women, which placed female former slaves at the bottom rung of a rickety ladder. Others argued that all should have the vote, including native tribesmen, who had as much a right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness as anyone else.

These were not abstract arguments. And neither is the concept of equal protection under the law, the 14th Amendment right that arose from that bloody disruption. People died in the post-Civil War years, often at the hands of vigilantes, and theirs are the kinds of sacrifices that we too often ignore in our current debates. Our modern attention span is notoriously short and narrow. That is our loss as a society, and it is good that books like “Ecstatic Nation” come along to prod us with our own past.

Irvine-based writer Martelle is the author, most recently, of “Detroit: A Biography.”

Ecstatic Nation

Confidence, Crisis, and Compromise, 1848-1877

Brenda Wineapple

Harper Collins: 736 pp., $35

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.