If cooks could kill ...

NOT since the “Godfather” hit man Clemenza told a henchman to leave the gun and take the cannoli has there been such an interesting moment for the intersection of food appreciation and morality in the movies.

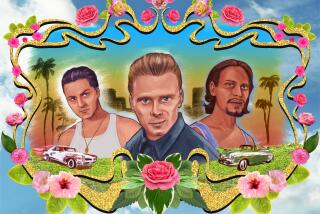

In the new Steven Spielberg film “Munich,” a group of Mossad assassins comes together around a dinner table to discuss their supersecret mission. They drink wine and feast on a variety of dishes -- meat, roasted vegetables, couscous -- at a table that is the epitome of a cultured and civilized gathering. The music soars sentimentally as they talk and laugh and philosophize.

This is just one of many scenes showcasing the cooking chops of the assassins’ team leader, an Israeli agent named Avner, played by Eric Bana.

Hollywood has a history of humanizing violent characters by showing them in the simplest, homiest domestic role -- as the cook, who nurtures and provides comfort (when he’s not shooting people through the head). But “Munich” takes this tactic to a whole new level.

In the book on which “Munich” is based, George Jonas’ “Vengeance: The True Story of an Israeli Counter-Terrorist Team,” there is no hint that the real-life Avner (not his actual name) ever lifts a pan. Jonas mentions that the Israeli doesn’t like the army’s “inedible food,” but that’s all the information we get.

Yet the filmmakers turn Avner into a world-class chowhound who apparently mastered his considerable cooking skills in a kibbutz kitchen. Why?

Avner is a character obviously in need of moral finessing. In retaliation for the butchery of 11 Israeli athletes at the 1972 Munich Olympics, he and his team track down and murder about a dozen men and one woman -- all of whom were in some way implicated in the attacks. In other words, these men kill only those who deserve to be killed. Still, innocents have a way of getting between an assassin and his gun.

Stacking the humanity deck in Avner’s favor, the movie gives us a guy who is familiar with all manner of produce, no matter how obscure. In a Parisian farmers market, he informs a Frenchman as to the nature of ramson (a leafy plant with a garlicky taste), correctly informing him it is out of season. Avner uses safe-house stoves to prepare almost absurdly bounteous (Spielbergian, one might say) dinners. The filmmakers are saying, “You can eat what this guy is serving you -- go ahead, trust him.”

The events depicted in “Munich” took place during what was for many Americans a less conflicted time in terms of assessing right and wrong in the Middle East. It would be 10 years, for instance, before the massacres at the Sabra and Shatila refugee camps in Lebanon, which inaugurated a much muddier moral era. In 1972, it was possible, at least for most American Jews, to see Israel as the unmitigated good guy in a terrible struggle. The need to remember that moment, perhaps, is why it was so important for the filmmakers to ensure Avner comes off as right-thinking a character as possible.

*

Life’s complexities

THE screenplay was written by Tony Kushner (“Angels in America”) and screenwriter Eric Roth (“Forrest Gump”). Like Arthur Miller before him, Kushner is a playwright whose writing ignites when he is assessing the complexities of people trying to live moral lives in an immoral world. The nourishing meals that Avner prepares and shares with his fellow assassins are clearly meant to establish the men’s essential integrity and desire for a normal life centered on family and home.

In one telling scene, when Avner is torn by doubt, he is inexorably pulled to the window of a high-end Parisian kitchen store, into which he stares mournfully. For today’s viewers, his jones for cooking translates into a longing for decency and a more sensible world, a world in which our hero would not be forced to become a killer.

What other earthly passion could perform these dramatic shorthands so effectively? Sex is too complicated; other obsessions tend to come off as OCD.

American food culture has traveled a distance since Clemenza uttered the single most famous line ever concerning ricotta-filled pastry. And though his cannoli was store-bought, the big man could cook. Clemenza is the one who teaches the young Michael Corleone to make tomato sauce -- a skill that will be as vital to the future mafia don as locating a planted gun in an Italian restaurant bathroom.

Clemenza decides to share his tomato sauce recipe in the grim hours just after Michael’s dad, Vito Corleone, has been shot (while shopping for oranges). “Hey, come over here, kid,” he says, “Learn something. You never know, you might have to feed 20 guys someday!” The recipe: olive oil, garlic, then “some sausage or meatballs if you like.” Next comes tomatoes, tomato paste, some basil, wine, and Clemenza’s “trick,” a little pinch of sugar.

For the characters, this is a healing moment, a reminder of daily life in the midst of their incipient grief. Director Francis Ford Coppola supplies these and many other homey details to help us identify with the characters, to ask us to see that they are human like ourselves. One film writer has counted 60 scenes in the movie that involve either food, wine or both.

*

Family and food

LEO Braudy, a film historian and Bing Professor of English at USC, says that before Coppola, gangster films “were about drinking. People were always going into bars.” It took Coppola and Italian culture to focus on the food. “ ‘The Godfather’ trilogy is about family and community and also about the breakdown of community -- the killing of others. What better, more basic image of community is there than people cooking and eating together?” he asks.

But all of this cooking and eating serves another purpose as well. Watching Clemenza’s chubby fingers handle the sausage, a viewer can’t help be reminded of all the death and carnage for which these men are responsible.

“The Godfather” was released the same year as the terrible events at the Munich Olympics. During the next 10 years, Coppola and also Martin Scorsese filled their work with plenty of sausage, garlic and wine, all of which helped us identify with nasty but hungry men.

In the early ‘90s, as food culture in America was maturing, Scorsese gave us cooking scenes with more precise and knowing references, such as one in “Goodfellas” in which a mob boss played by Paul Sorvino uses a razor to slice garlic as thin as truffles, so thin it will “liquefy in the pan with a little olive oil,” according to another mobster’s voice-over.

Mainstream American filmmakers didn’t show any interest in tenderizing tough guys by showing them as cooks before the ‘70s, despite the occasional suburban grilling scene. Our most interesting bad guys kept their hands clean in the kitchen. It’s impossible to imagine Humphrey Bogart’s Philip Marlowe, for instance, in need of an apron. The most famous gangster food scene would be James Cagney squashing grapefruit in the face of his moll girlfriend Mae Clarke during breakfast in “The Public Enemy.” He didn’t cook the grapefruit.

In vintage cinema westerns, both good and bad guys were always cooking coffee or beans over the campfire; it showed their self-sufficiency. But the western attitude toward food is best summed up by Sam, a bar-and-grill proprietor in “Bad Day at Black Rock.” When the Spencer Tracy character asks him what’s on the menu, Sam answers, “Chili with beans or chili without beans.” When Tracy winces, he comments: “You don’t like the taste, that’s why they make ketchup.”

If the film were made today, Tracy would leap over the bar and whip up some farm-fresh eggs and fennel sausage. (He does don an apron in “Adam’s Rib,” but that’s another genre.)

Interestingly (and, perhaps, suspiciously), in “Munich,” Avner’s food expertise is historically extremely improbable.

According to Jonas, the real-life Avner was born in what was called Palestine in 1947 -- the year of partition and the start of contemporary hostilities. It was, to put it mildly, a busy time and place and hardly a hotbed of culinary culture.

Food and wine critic Daniel Rogov, writing on Israel’s food history for the Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs, notes that the people who lived in Jerusalem 3,000 years ago “probably dined better than those who lived there just half a century ago.”

In 1948, the year the state of Israel was founded, there were only two cheeses available, one called white and one called yellow, “neither one of which had charm or appeal.” On the food front, he notes, things did not begin to improve until the mid-1970s.

The real Avner would not have known a ramson from a rutabaga.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.