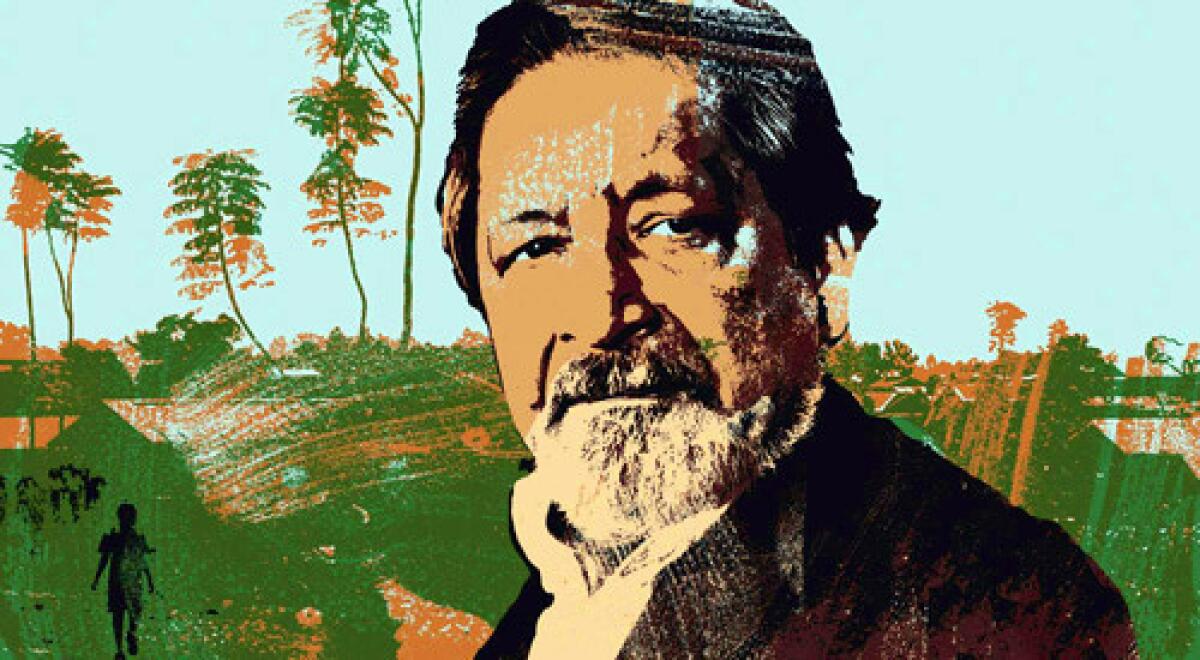

Book review: ‘The Masque of Africa: Glimpses of African Belief’ by V.S. Naipaul

The Masque of Africa Glimpses of African Belief

V.S. Naipaul

Alfred A. Knopf: 256 pp., $26.95

V.S. Naipaul’s world is what it is, a place with little sentimentality for the powerless.

That world has been constructed from more than five decades of writing by the Trinidad-born author, who took it upon himself to travel to faraway places and, among other things, to explain displaced persons like himself, an East Indian deposited by colonialism in the West Indies.

Naipaul traversed Africa, India and the Muslim world when travels to these places were not plebeian acts but intrepid affairs. His take on post-colonial societies has drawn adulation for his exceptional candor — and ire for his brutal portraits of his subjects.

He has often called such places deformed. Their people reduced to “mimic men.” Arguably, the line that sums up Naipaul’s worldview is the famous opening sentence in his 1979 masterpiece “A Bend in the River”: “The world is what it is; men who are nothing, who allow themselves to become nothing, have no place in it.”

The first six words became the title of Patrick French’s 2008 authorized biography of Naipaul. It portrayed Naipaul as a cold-blooded, egomaniacal genius who ended up emotionally slaying the people who loved him.

Naipaul, who has racked up more than two dozen works of fiction and nonfiction, and the 2001 Nobel Prize in literature along the way, keeps producing books. Many of his later works reprise his earlier ones.

His latest offering, “The Masque of Africa,” does just that. It is an account of his travels to Uganda, Ghana, Nigeria, Ivory Coast, Gabon and South Africa. Africa is familiar ground. “In a Free State,” as well as “A Bend in the River,” detailed his earlier exploits on the continent.

When Naipaul adds to his body of work, readers are armed with a lifetime of context — his books, writings and interviews. He has expressed firm opinions that as the continent approached modernity, it remained a “land of bush” and “has no future.”

And in his earlier works, Naipaul’s take on the continent comes through: Traditional beliefs hold sway. “The bush was full of spirits; in the bush hovered all the protecting presences of a man’s ancestors,” he writes in “A Bend in the River.”

Africa and its instability have always scared Naipaul. He says so. In another book, “The Enigma of Arrival,” Naipaul writes: “The Africa of my imagination was not only the source countries — Kenya, Uganda, the Congo, Rwanda; it was also Trinidad, to which I had gone back with a vision of romance and had seen black men with threatening hair.”

With a guilty verdict secured, Naipaul, now 78, goes back to Africa to explore the theme of African belief. This time, the assignment is a cinch. With Trinidad serving as a point of reference, Naipaul starts in Uganda, where in 1966 he served as a writer in residence at Kampala’s Makerere University.

From his perch in the Aga Khan-owned Serena Hotel, Naipaul interviews Ugandans from all walks of life, travels the countryside and visits sacred places. The damning evidence comes when he visits a witch doctor who breaks out a photo album to show him pictures of his clients: all famous local people who, Naipaul implies, should know better.

To further prove his point, Naipaul relies on the not-so-reliable Ugandan newspapers, which two or three times a week carried items from various parts of the country about witchcraft. At the end of a day of travel, Naipaul sees some schoolchildren in uniform, heading home to their modest dwellings. “There would be no jobs for most of the children we could see — some dawdling their way home now, killing time in spite of the heat.” That was a topic the knighted Naipaul could do well to explain, but unfortunately that’s not the purpose of the book. The scene presented the opportunity for Naipaul to delve into a more relevant inquiry. Why have meaningful measures of prosperity eluded much of Africa since independence? And how much of the blame can be placed on conditions on the ground: poverty, corruption and leaders eager to exploit tribal conflicts to hold onto power?

He moves on to Nigeria, where his mind-set is on full display. Naipaul spends time getting to the bottom of Mumbo Jumbo, the fictitious character that inspires dread and order in Nigerian society.

Critics who have suggested that Naipaul has a jaundiced eye toward Africa would find heaps of ammunition here. Before exiting the infamous Lagos airport, Naipaul sees sorcery everywhere. A Nigerian diplomatic passport is “almost a fetish.” Nigerians waiting for their luggage to tumble onto the conveyor belt looked like “people who believe in magic.”

In Nigeria, though, Naipaul is at his mischievous best. He recounts an experience in which he asks if his fictional daughter will get married. After a ritual with shells, tiny gourds and an incantation, the babalawo responded that the girl was not going to get married. Some money and a few rituals could fix that. Naipaul shoots back: “But what he told me is good. I don’t want the girl to get married.”

Given his reputation as a meticulous researcher, Naipaul makes some baffling declarations. “Africa is no longer polygamous; only the Muslims among them have many wives.” Really? A little fact-checking could have easily remedied that error.

Naipaul says that when he travels, he seeks to examine a theme and a state of mind. But “The Masque of Africa” lacks a compelling overarching frame. One thing that is recurring is Naipaul’s constant worry that his tabs for witch doctors, taxi drivers and fixers will pile up. In Ghana, he skips out of a meeting with a high priest when he merely senses his bill “appeared to be going up and up.” He leaves it to an acquaintance to pay the bill, noting that “it wasn’t fair, but it was something he could do, and do well.”

Another commonality is his obsession with felines. In country after country, Naipaul, a cat lover, takes frequent detours to comment about Africans’ mistreatment of animals, especially cats. Visiting the home of former Ghanaian ruler, Jerry Rawlings, he notices a beautiful gray and white kitten. “It was the first happy kitten I had seen in Ghana,” he writes. “I began to be prejudiced in favor of the house.”

Peculiar asides like these make one wonder why Naipaul bothered to go back to the scenes of his success. On previous journeys, you could count on this critic of modern societies to investigate an issue, lay out the evidence and let people make up their minds. “The Masque of Africa” does just the opposite. It sets off to prove an obvious point and hammer it home — again and again. It leaves Naipaul looking weary, out of touch and open to ridicule.

At this stage in his career, Naipaul should be writing books that are supernaturally good. This one is merely about the supernatural.

davan.maharaj@latimes.com

Maharaj, managing editor of The Times, also served in Africa as a correspondent for the paper.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.