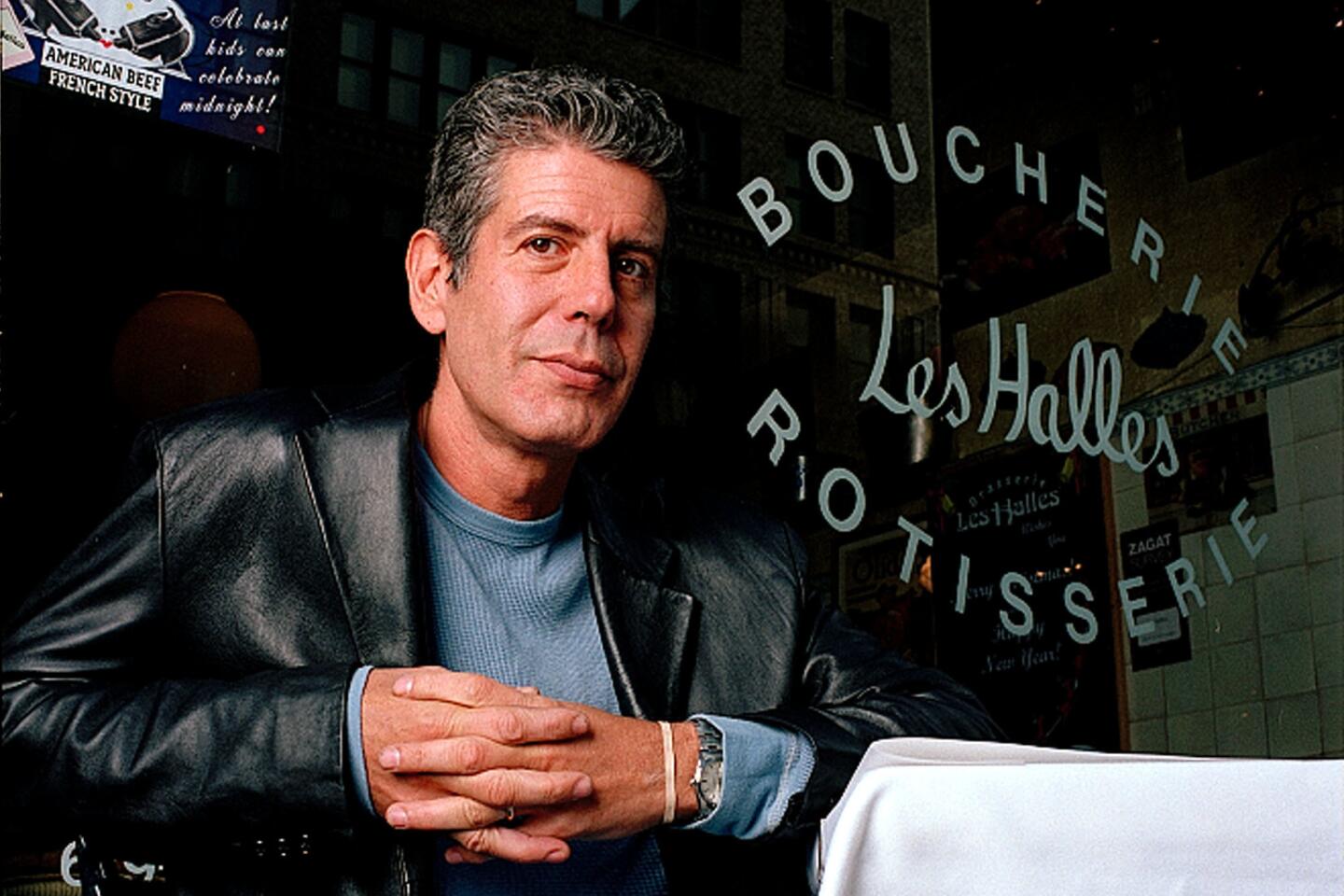

He may have had a bad boy persona, but Anthony Bourdain was lovely, loyal and so damn smart

Anthony Bourdain, the sardonic intellect who shone a lens on how food revealed the lives of people no one previously thought about and places few visited, has been called many things over the years, but at the core, he was a writer and commentator. And even from the beginning, he was a correspondent.

Bourdain’s groundbreaking memoir, “Kitchen Confidential,” was written from the point of view of an outsider, reporting and trying to make sense of a chaotic, often out-of-control life: his own, and that of the unsung, unknown working kitchen.

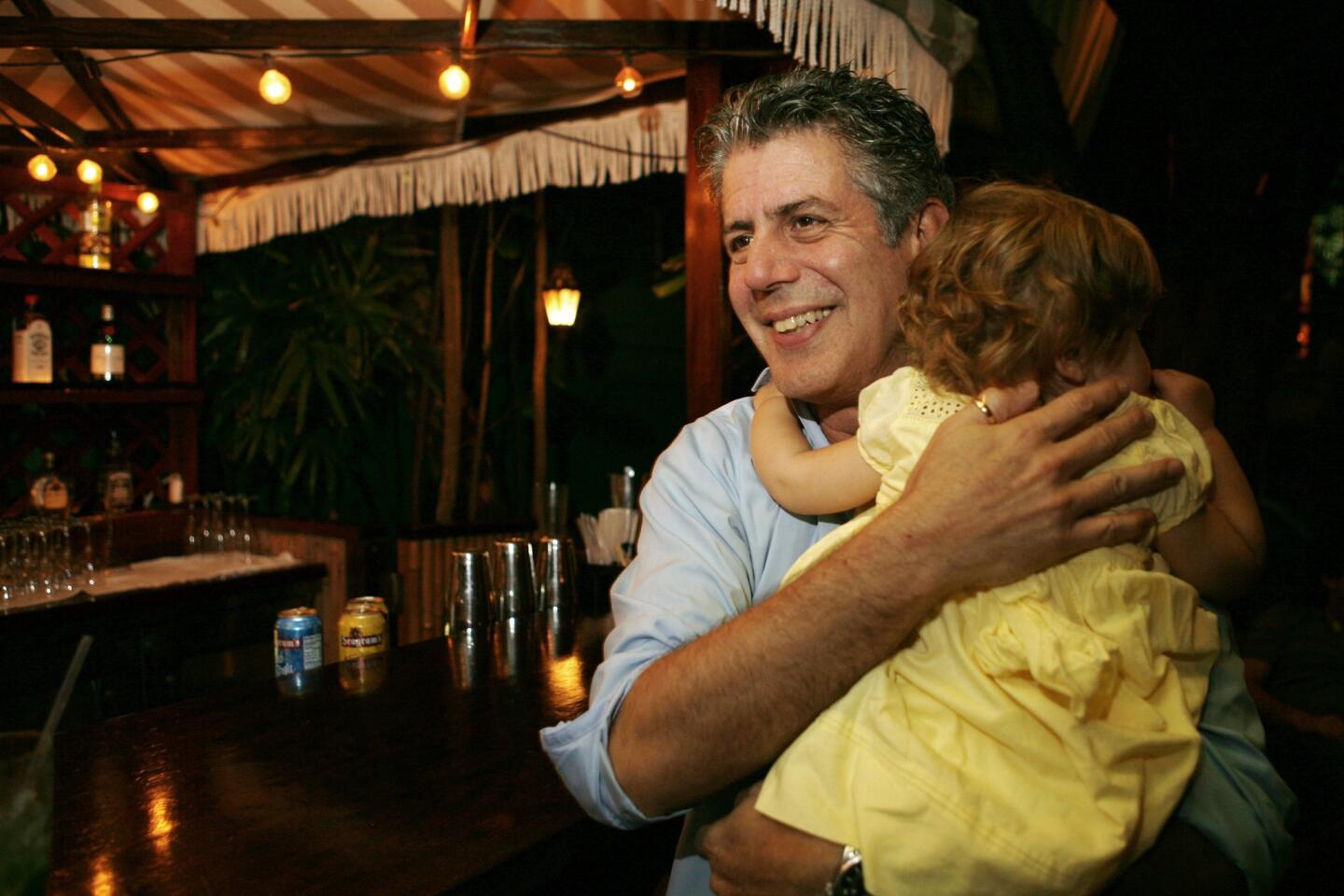

The book catapulted a shy, self-effacing man into a sudden spokesperson for the marginalized immigrant — and also imprinted him as the adventurous bad boy. Bourdain was a person who gave voice and status (sometimes too much) to the misfits of these unseen places, and who had such compassion for the everyman of the world trying to find joy amid a life bowed to power. Yet he was so unseen himself — even as he was everywhere, from the Travel Channel to CNN — that when news came of his death on Friday from an apparent suicide, those close to him didn’t see it coming.

Before “Kitchen Confidential” was published in 2000, I received an advance copy at KCRW and grabbed it on my way to the airport for a flight to Italy. I devoured — a good word — the book on that flight, with outbursts of intense, and probably too-loud laughter.

I was still occasionally working on the line in my restaurants, and it was absolute validation to be recognized as doing an unsung, somewhat heroic job in the eyes of such an incisive voice. It was heady.

That recognition continued when he walked into the studios of KCRW, looked at the instantly recognizable marks — oven scars, both new and old — on my forearms and said, “Ah, a member of the club.”

Anthony Bourdain opened the working-class kitchen to the world and the world to us »

Previously, the only acknowledgement of the work that required those arms to go in and out of the oven was from my mother or a man saying, shouldn’t you wear long sleeves to cover those up?

We didn’t know we could be a club. Most of us chose the life not because it was celebrated on TV but because we were called to it through an obsession with food, or we ended up in a too-hot, too-loud, chaotic place because it was the only place that would have us or where we felt like we belonged. Part of me feels like the real reason I ended up working a line was my horror at the idea of having to wear stockings to work every day and sitting at a desk.

In this moment of societal reckoning of how women have been treated, it’s been all too easy for some to vilify Bourdain for creating a culture of “meatheads,” as he called it. But until he wrote “Kitchen Confidential,” no one looked behind the swinging door with the porthole window.

Why would you, when “chef” meant the few tall-hatted men representing codified cuisines serving well-heeled customers in restaurants most of us never entered. Cooks were meant to be invisible.

Bourdain was so obsessed himself with unpacking the chef’s life and those years spent in a drugged-out haze that his first published writing, five years before “Kitchen Confidential,” was a mystery novel titled “Bone in the Throat.” That idiom — meaning “a source of continuing annoyance” — may well be the key to the restless intellect that finally moved him to leave the kitchen and become its documenter.

The TV Bourdain of “A Cook’s Tour,” still a young man, reinforced the persona of the bad boy, willing to eat anything anywhere, and reified the idea of the macho knife-loving male chef. We saw him travel the world bonding with other, mostly male chefs in “the club.” But even that title is a literary reference — to the British brief “Cook’s Tours” organized by travel company Thomas Cook in the 19th century.

The persona may have been “bad boy,” but the person himself not only was literate, but lovely, loyal, compassionate and helpful. And smart. So, so damn smart.

Bourdain was always more than he seemed. And the public really started to see this, with the groundbreaking Beirut episode of “No Reservations,” when Bourdain and his crew were stranded when the Israel-Lebanon conflict started. The meager edited footage turned the episode into a difficult-to-watch existential meditation on how awful the world can be even while people remain capable of bridge-building. His reporting became more pointed, idiosyncratic and fearless.

The Iranian episode of “Parts Unknown” was emblematic of the man who needed to meet and reveal the humanity of people caught up in complicated historical moments of unequal power.

It is ironic that Bourdain became the voice of a group of men in the hospitality industry who used him as an excuse to exercise their power in such an ugly way. He rightly spent a lot of energy in recent years to divorce himself from that kind of behavior.

As a woman who lost her own father very young, I ache for his daughter. And how sad that it was Eric Ripert, a chef and a Buddhist, who found his friend beyond reach of such tremendous despair.

If you or a loved one is considering suicide, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at (800) 273-8255.

Kleiman ran Angeli Caffe for 27 years. She’s the longtime host of KCRW-FM’s “Good Food” and a member of the James Beard Foundation’s Who’s Who of Food & Beverage in America.

More to Read

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.