Review: Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra serves up a sandwich of sad and sweet

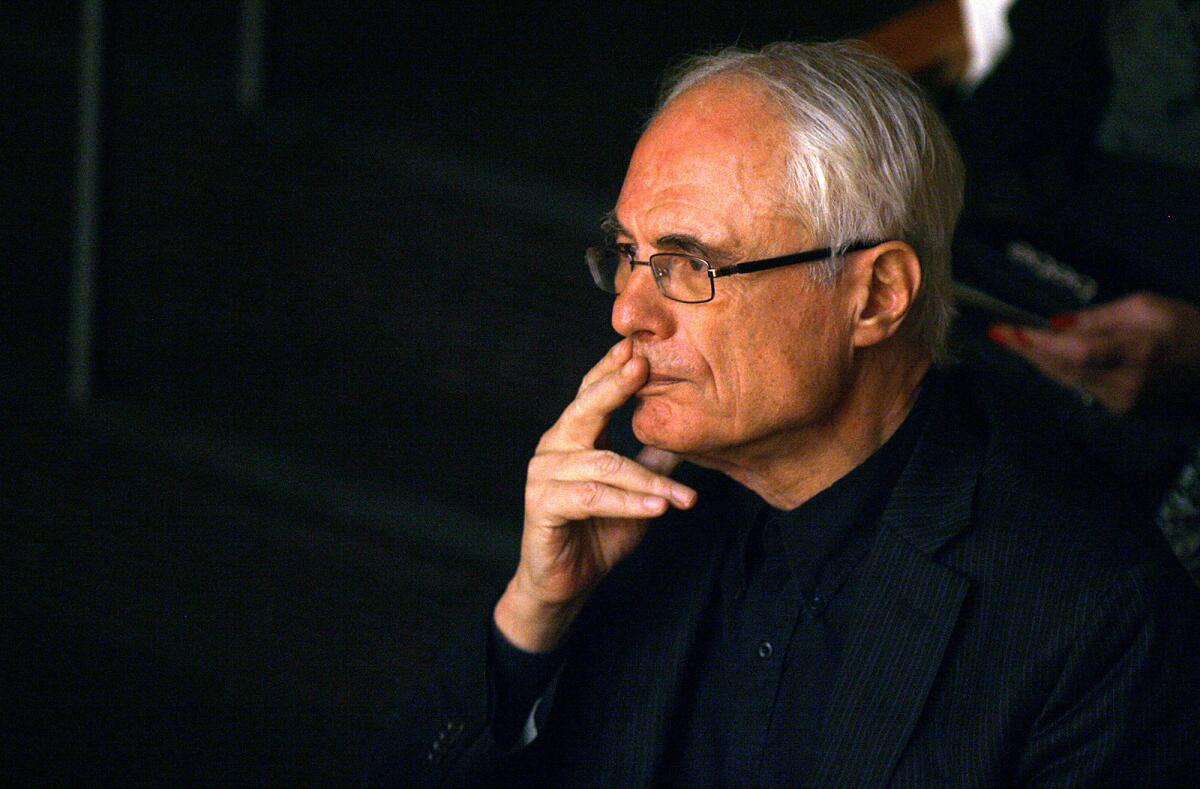

Not quite two weeks after turning 60, Jeffrey Kahane began his 20th and final season as music director of the Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra last weekend. He was buoyant, opening with one of Bach’s most overtly jubilant cantatas and ending with what the conductor described as the most joyous symphony ever written, Beethoven’s Seventh. In between came a candidate for the saddest violin concerto, Armenian composer Tigran Mansurian’s Second, titled “Four Serious Songs.”

Such a musical sandwich! The sweet bread of life housing a bitter filling of death and serving as a reminder to savor each bite, honeyed or otherwise; it may be your last.

We’ve had no better minder of the last gasp than Bach. His approximately 200 church cantatas are sermons on the meaning of being. When solemn and summoning regret, they make us grateful. When exultant, as in No. 51, which Kahane chose to open the program Sunday at UCLA’s Royce Hall, they nonetheless provide a bigger spiritual picture. For Bach, goodness is inseparable from worthiness.

That the performance of “Jauchzet Gott in allen Landen” (“Rejoice in God in All Lands”) offered too little reason for rejoicing was untypical of Kahane, who has led deeply felt Bach performances with LACO over the years and who is also a Bach pianist of renown. It was also untypical of an evening better characterized by the fervent performances that followed.

In this cantata for solo soprano, Joélle Harvey sang loudly but with emphasis on rounded tone (which was gorgeous) and vowels not words, few of which were intelligible. (There was no translation of the German text.) David Washburn, the orchestra’s impressive principal trumpet, played his high-spirited solos loudly. Kahane conducted from an inaudible harpsichord and, in the middle section, a barely audible portative organ. The indistinct orchestra could have been in an echo chamber next door.

SIGN UP for the free Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

A minute or two was spent arranging the stage for a larger orchestra. Harvey sang, as a kind of encore (although officially part of the program), Mozart’s equally exuberant “Alleluja” from his “Exsultate, Jubilate.” Here the soprano didn’t need consonants for that single word of text. She was thrilling. The orchestra came into focus, animatedly conducted by Kahane. (Harvey will need to find every one of those consonants, though, when she sings Pat Nixon in the Los Angeles Philharmonic’s performance of “Nixon in China” later this season.)

Mansurian’s concerto might have been, but was not, a downer. Dean of Armenian music and a composer with close ties to the Armenian community in Glendale, he has an international following thanks to a series of ECM recordings of arresting, otherworldly music. He has been notably ignored, however, by the local ensembles with the exception of the devoted Dilijan Chamber Music Series. Violinist Movses Pogossian, a close associate of Mansurian’s who heads the Dilijan series at L.A.’s Zipper Concert Hall, was soloist.

Written a decade ago when the composer’s wife was dying of cancer, the concerto takes its inspiration from Brahms’ final accommodation with death, his “Four Serious Songs.” And yet Mansurian (more than Brahms) has that Bachian ability to show death as what makes life possible.

Pogossian’s violin solos conveyed all this with piercingly focused tone and heart-stopping intensity. The melodic writing is consoling, but the articulation has elements of anger, especially in the minute-long third part, a violin solo during which every bow stroke feels a fraction second away from a broken heartbeat lifeline.

The final movement began in so quietly it sounded as though Pogossian was playing on one half of one string, with the 15-member string orchestra coming in with tentative gentleness. This is when a phone went off in the audience, blaring what should have been a mood-destroying stupid tune. But the sheer will of Mansurian’s music, and of Pogossian’s performance, remained on course, making the contrast between this world an any other all the more remarkable.

Kahane now was ready for Beethoven’s Seventh. He gave the audience a compelling introduction by explaining how he had struggled during the last 17 years to learn classical Greek and Latin in order to read the Homer, Virgil and the rest of the ancient authors in their original languages. His reason, he said, was not because they form the basis of Western civilization, but because of their role in the development of music.

Beethoven, for example, rides Homer’s rhythms in his Seventh, as Kahane demonstrated. Wagner may have famously called it the apotheosis of the dance, but Kahane revealed it more like the apotheosis of the Greek epic — bigger than, but every moment infused with, life.

Kahane didn’t boldly emphasize Beethoven’s rhythms. His performance was relatively conventional, following a middle ground between modern and period performance practices. But it had the weight of history, showing the deep semantics of a symphony to be, through an urgency of every musical gesture, timeless. It wasn’t Bach’s night, but there was enough rejoicing in Beethoven to go around for every land.

ALSO

For opera lovers, at last a ‘Rake’ for L.A., bearded lady and all

Plácido Domingo’s sound and fury in L.A. Opera’s ‘Macbeth’

11 don’t-miss shows: ‘Breaking the Waves,’ John Adams’ 70th, Philip Glass’ ‘Akhnaten’

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.