Envisioning the self before the age of the selfie in ‘Portrait of the Artist’

In an age saturated with selfies, sometimes it feels good to put the

“Portrait of the Artist” does just that, collecting images of artists from the vast British Royal Collection, which includes work by Sir Peter Paul Rubens, David Hockney, William Hogarth and more. Both portraits and self-portraits comprise “a book about the image of the artist and how that image — in reality and in perception — has changed over time,” write Anna Reynolds and Lucy Peter, who along with Martin Clayton, co-authored the book.

Self-portraiture is now so ubiquitous that it’s interesting to discover it only gained momentum during the 15th century, around the same time the “cult of the artistic personality,” write Reynolds and Peter, also arose. Self-portraits can be practical: some artists lack the funds to pay for a professional model, or they’re sketching out a new technique and want to keep the stakes low. The form satisfies instincts toward immortality, self-reflection and self-aggrandizement (#selfie), not to mention the human imperative to investigate if others perceive us as we perceive ourselves.

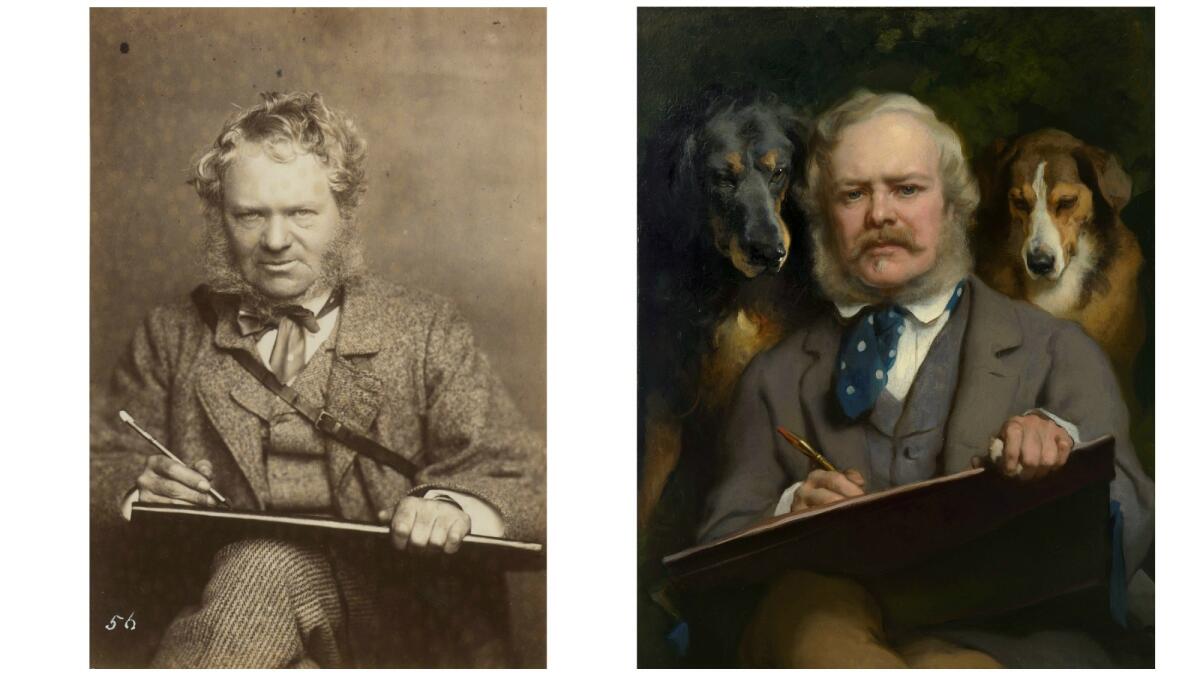

Like many art books, “Portrait of the Artist,” out this week from the Royal Collection Trust and the University of Chicago Press, accompanies reproductions with historical context and analysis, which is particularly fun for works in conversation with one another, such as this photograph of Sir Edwin Landseer paired with his self-portrait.

To compare and contrast:

Sir Edwin Landseer's "The Connoisseurs: Portrait of the Artist with two Dogs"

- Landseer enjoyed the company of dogs in his studio while he worked, and those in this painting are thought to be his own dog on the right, Lassie, and a dog named Myrtle belonging to one of his patrons.

- Landseer apparently had an arch sense of humor: this self-portait is titled “The Connoisseurs,” and in portraying the two dogs as “scrutinizing his drawing,” he suggests “that the untutored judge is better than the tutored.”

- Notice anything out-of-line when comparing the two images? “His painting hand and the buttons of his jacket have been reversed, while his parting and the direction of both his crossed legs and his drawing board correspond to his mirror image.”

Unlike Landseer’s portrait and self-portrait, which bear a clear resemblance, Sarah Bernhardt’s presentation of herself hews less to visual accuracy than to achieving a kind of spiritual likeness.

Sarah Bernhardt's "A Self-Portrait as a Chimera"

- This bronze self-portrait as a chimera, or sphinx, is actually an extremely ornate inkwell. Other examples are known; Bernhardt presented them to distinguished friends and patrons as gifts.

- At the time of this self-portrait’s creation, one of her most famous roles was in Octave Feuillet’s “Sphinx.” The play may have served as inspiration for the bronze, a kind of calling card.

- If the portrait at left mythologizes Bernhardt as an artist, she takes it a step further in her self-portrait, mythologizing herself as, well, myth. The chimera is a hybrid creature in Greek mythology.

Despite their obvious differences, two self-portraits by Lucian Freud and David Hockney share an affinity. Is it the texture? The expression? Both artists appear forthright and unsentimental. Amateur artists and selfie-takers take note: Hockey embraces the iPhone.

David Hockney’s “Self-Portrait, 6 April 2012”

- This self-portrait was drawn on an iPad and ink-jet printed, but Hockey has also worked on the iPhone, sketching bouquets to send to friends. “People from the village come up and tease me: ‘We hear you’ve started drawing on your telephone,'” Hockney told the New York Times. “And I tell them, ‘Well, no, actually, it’s just that occasionally I speak on my sketch pad.'”

- Hockney was appointed to the Order of Merit in 2012. Wasting no time, he created this drawing for the Order of Merit portrait series in the Royal Collection just four months after receiving the honor. As a medium, one of the iPad’s advantages is speed.

- Hockey favors the iPad’s Brushes app for landscapes, which allows him to play back the creation of the drawing “so that he can watch himself at work.” In this self-portrait, he uses app “to capture the out-of focus effect of a face seen from very close.” Note the finely drawn hair, as scratchy white lines, top left.

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.