How ‘The Walk’ came into existence

Joseph Gordon-Levitt portrays Philippe Petite in a scene from, “The Walk.”

Robert Zemeckis isn’t necessarily willing to spill all the technical secrets of how he made “The Walk,” his new movie about Philippe Petit and the Twin Towers that brings the building to life, with us atop them. And let’s be honest -- the nitty-gritty of frame rate and digital-animation techniques might be a little mystery-diluting anyway.

But how “The Walk” came to be, in a larger sense, is a more decipherable puzzle. It contains jigsaw pieces that would not be easy to procure in the first place, let alone fit together: a director with an obsessive streak, a studio executive willing to roll the dice on bold material (at the right price), an actor who wanted to tackle the challenge (with the right accent), a building and subject laden with the stuff of fable.

With “The Walk” now open in theaters, in its Joseph Gordon-Levitt and IMAX 3-D glory, here’s a look at the elements of the film and how they came together.

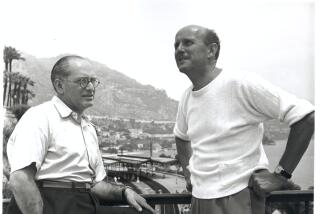

The production. While it seems to be arriving well after that Philippe Petit renaissance that arose in the wake of James Marsh’s 2008 documentary “Man on Wire,” Zemeckis was actually interested in turning Petit’s story into a movie a few years before that, when he read Mordicai Gerstein’s 2003 picture book “The Man Who Walked Between the Towers.” He soon flew Petit, who lives in upstate New York, to meet him in Southern California. The two dined, and Zemeckis sold him on the idea that a scripted movie was the right way to go (without Petit playing himself, an early notion floated by the lens-loving wire-walker). “Everything about the story -- the courage Philippe had, the bigger-than-life adventure -- struck me as surprising,” Zemeckis said. “And then to present the passion of this character as this cinematic spectacle -- that’s what makes the movies the movies.

SIGN UP for the free Indie Focus movies newsletter >>

The budget. It cost $35 million. Yes, $35 million. That’s not a misprint. In an era when even garden-variety action-adventures come in at a high multiple of that, it’s an unfathomable number -- one usually associated with mid-budget genre movies, not sky-tickling effects pictures. To get there, producers did a lot of trimming. Production days were slashed; locations tossed aside. (An early thought to shoot in Paris and New York, where the film takes place, was scrapped in favor of rebate-friendly, currency-favorable Montreal.) Zemeckis did his usual fee-waiving thing. The crew worked with Atomic Fiction, a boutique visual effects agency, to make it all look much richer and lusher than most computer-diddled movies do. And a movie that should have cost $100 million went for a third that. “From its original iteration to its actual budget,” says “Walk” producer and longtime Zemeckis partner Jack Rapke, “is night and day.”

The studio. The project was initially at Disney, when Dick Cook was still running the show there, two regimes ago. A few flops and some management changes changed all that. Gone was Zemeckis’ large-scale animation company ImageMovers and the 400 people who worked for it; gone, too, was the Petit passion project. Zemeckis and Rapke extended their hat to every source looking for money -- independent, studio, foreign. No one bit. Zemeckis grew frustrated; the technology, though, was getting better. Zemeckis went and made another movie, the 2012 character drama “Flight,” in the interim. Tom Rothman, the longtime head of Fox, went to a gig on the Sony lot in the interim too, running a revived Tri-Star.

Rothman had a history with Zemeckis (”Cast Away,” e.g.). And he possessed a willingness to do big, upscale digitally-oriented projects if they could be done very inexpensively. (“Life of Pi,” e.g.). He said Sony would make the movie if Zemeckis kept the cost really low. And now the technology had improved to the point that that was at least conceivable. Zemeckis said he’d do it. “It creates a lot of heartbreak when you have a movie that you get everyone excited about and then can’t make,” the director said. “In the case of ‘The Walk,’ I’m walking around with this, so to speak, for almost nine years. But I never had that feeling it wasn’t going to get made. It’s really interesting. I always knew it would see the light of day.”

The director. Zemeckis has been telling Hollywood they’ve been missing something for a while, taking on non-franchise projects others might describe as quixotic. Then he runs into windmills and proves them wrong (mostly). It happened on “Forrest Gump,” nearly shut down a few weeks before production began in South Carolina. It happened on “Romancing the Stone,” a movie thought to be such a dud that Zemeckis was fired from his next film “Cocoon” after the studio saw an early cut. It happened on “Back to the Future,” when Zemeckis insisted Michael J. Fox was the guy even after Eric Stoltz, whom he’d gone to when he couldn’t get Fox out of his “Family Ties” deal, had been shooting the film for five weeks.

It’s yet to happen on his three motion-capture movies between 2004 and 2009, one of which (“The Polar Express”) was a hit and two of which (“A Christmas Carol” and “Beowulf”) weren’t; the industry and critics still raise their eyebrows on that one. And though the move to “Flight,” “Walk” and his next movie -- a World War II romantic thriller starring Brad Pitt and Marion Cotillard -- would suggest Zemeckis has left the mo-cap moment behind, he says he might well return, especially after the technology is perfected in the coming years. Other tech-minded experiments may await too. His friend and old writing partner Bob Gale recently saw “Unfriended,” Leo Gabriadze’s genre movie told via computer screen. Zemeckis has wanted to do something along those lines, Gale said, and the writer brought it to Zemeckis’ attention as a case study for how it might be done. There may be more Dulcineas to come.

The actor. Gordon-Levitt speaks French, has an interest in the circus arts and was also enamored with Petit, whom he met and conducted an intense wire-walking camp with. But it’s the accent that may really stand out to filmgoers. Gordon-Levitt said he was nervous before undertaking it. “It was a big swing. A really big swing.” But then he thought about Tom Hanks’ uppercut in “Forrest Gump” and realized he needed to try it. And Petit really does talk this way -- with a kind of exaggerated lilt that almost builds the swagger into his vocal cadences. So an accent was born. You may still be hearing it long after you see the movie.

The subject. Sometimes you see a movie about a guy, then you see that guy, and they have nothing to do with each other. Hollywood broadens and makes more colorful and all that. That won’t happen here. Petit is very much around and, at 66, remains as loquacious and larger-in-life as he is in the film. The screen version may even be toned down. At the New York Film Festival world premiere last weekend, he interpreted a stage shout-out from Zemeckis as a signal to stand at his seat. That is, stand on his seat. Actually, it was the top of the seat, the narrow part that requires some pitching forward and backward to stay balanced, which he did as he waved to the crowd. It might have been a planned bit of stagecraft: the house lights came up as Zemeckis called his name, enabling the audience to see it in full effect. Yes, Petit is very much around.

The audience. Can it actually work? Can a movie that’s, at bottom, about one man trying to take a walk draw in millions of moviegoers? Though the on-screen stakes are low, the studio believes it can. “The reason I think it feels important is because dreams are personal,” said Rothman, who since production began has come to have more skin in the game -- he now runs Sony’s motion pictures unit. The spectacle could help too. “One of the things you have to do when making original movies in this age is give people a reason to get off the couch,” Rothman said. “And this does. It’s quite simply something you can’t get on TV.”

The film is going to take its chief competition from “The Martian,” Ridley Scott’s similarly “man-alone in an otherworldly place adventure” that opens this weekend. That movie will debut to a monster number and keep attracting filmgoers in the weeks to come. “The Walk” must divert some people away, or get them to come to its movie too--building on post-screening word-of-mouth that will be strong but likely also to focus on the walk of the last 30 minutes rather than the entire movie. The studio can, however, rely on the patriotic feeling it stirs: One of its big thematic concerns is what was lost, at least physically, after Sept. 11, 2001.

The building. That leads to the inevitable. Yes, “The Walk” is an ode to the Twin Towers as much as the power of will and ambition, underscored in a melancholic ending suggesting that it’s both gone and can live in the imagination. That it’s all done seamlessly -- the buildings feel real, not generated on a computer screen -- enhances the effect and makes the loss feel that much more tangible. Which makes sense, as Sept. 11 is what motivated filmmakers to tackle the project in the first place. “If the towers were still here, we would not have made the movie,” Rapke said. “Because it has a mythic quality to it. It’s almost a fairy tale. There were these beloved towers and now they’re not here.”

Twitter: @ZeitchikLAT

MORE:

Robert Zemeckis high-wire spectacle ‘The Walk’ is more adventurous technologically than dramatically

Joseph Gordon-Levitt mentored by daredevil Philippe Petit for ‘The Walk’

‘Everest,’ ‘The Walk’ studios gamble big with limited-release strategy on Imax

Director Robert Zemeckis walks ‘The Walk’ as a quixotic filmmaker

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.