Balcony collapse spurs criticism of Berkeley’s apartment inspections

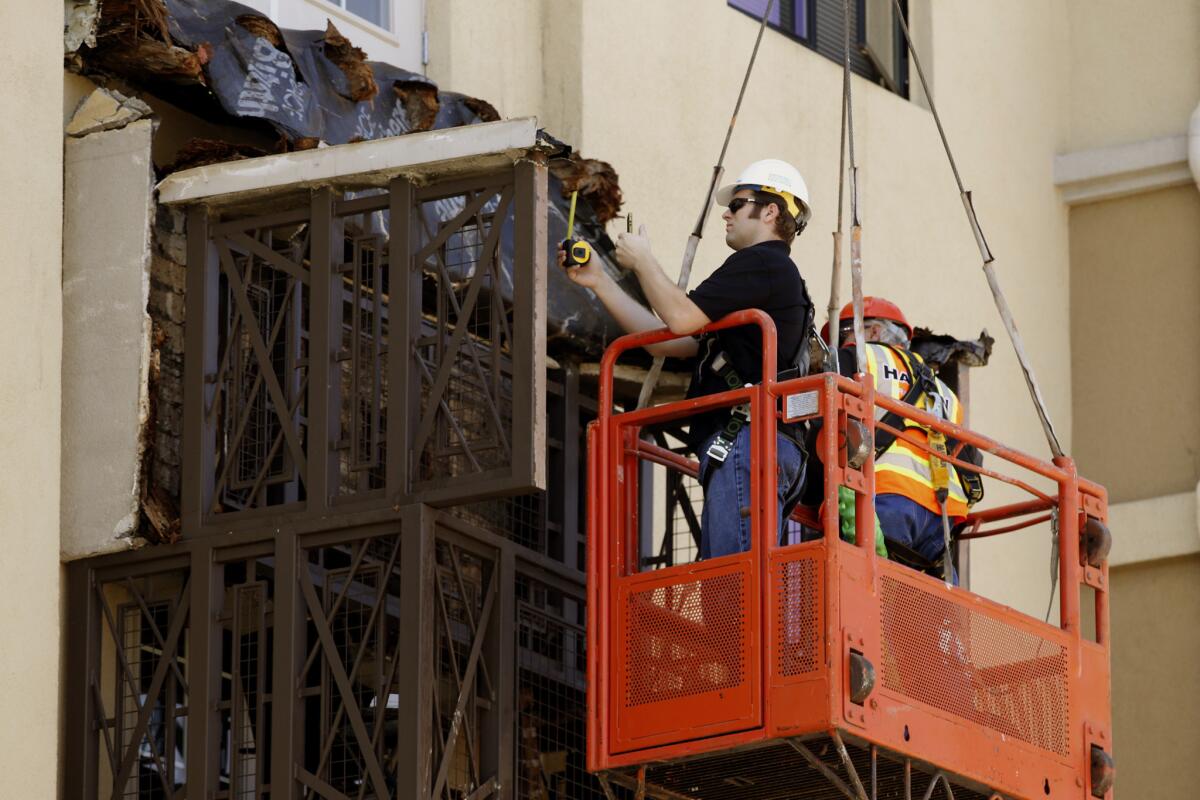

Engineers assess the damage and look for answers after a balcony collapse at an apartment in Berkeley killed six students and injured seven more just a few blocks from UC Berkeley.

Fifteen years ago, landlords in this university town were not required to conduct annual safety inspections of its aging rental stock.

That changed after a family from Southern California — dropping their daughter off at UC Berkeley for her third year — died in a fire at an apartment house for students. The building had no smoke detectors. The window of their second-floor bedroom was sealed shut, trapping them inside.

Those deaths and two others tied to building code violations prompted city leaders in 2001 to require landlords to inspect rental units annually and file proof with the city that was to be backed up by a robust program of random inspections.

But after the apartment balcony collapse last month that killed six people and severely injured seven — almost all of them students from Ireland — some residents and officials say that Berkeley’s rental safety program has eroded into an honor system, where the self-inspections done by landlords are rarely checked. They are demanding close oversight on par with other rent-heavy cities such as Seattle and Los Angeles.

Berkeley’s three code inspectors checked 525 of the city’s roughly 28,000 rental units in the fiscal year that ended June 30, records show. Through the first 10 months of that period, they cited four landlords for failing to conduct their own inspections.

“There is no enforcement. It is toothless,” said Jesse Townley, chairman of Berkeley’s Rent Stabilization Board and an advocate for mandatory city inspections.

Two hundred of those inspections were state-mandated, made only after tenants filed complaints alleging unsafe conditions. The other 325 were examined under a city-mandated random inspection program that when it was launched in 2001 was envisioned as reaching half the city’s rental units that become vacant every year.

By comparison, inspectors in nearby Richmond said they canvassed 2,400 of the blue-collar town’s 13,600 apartments this past year. Los Angeles inspects every one of its 730,000 multi-family rental properties every three to five years.

Even before the disastrous collapse June 16, where support beams had been weakened by dry rot, officials had debated whether to toughen inspection requirements but rejected the idea.

Then, late last month, as Irish families were still in town to claim the remains of victims and comfort the survivors, the city planning staff recommended that landlords be required to inspect all existing balconies. The City Council was slated to take up the proposal Tuesday night.

The debate comes amid surging rental costs and a construction boom in Berkeley, which has drawn young professionals looking to avoid San Francisco’s even more overheated housing market. Still, a small two-bedroom unit in downtown Berkeley can rent for $4,000 a month — a roaring market that has attracted deep-pocketed investment firms eager to build apartment complexes as tall as 18 stories that would loom over the downtown skyline.

“It shouldn’t take a tragic situation to make this a priority,” said Berkeley City Councilman Jesse Arreguin, who proposed a system of mandatory inspections at a public meeting with the mayor and housing officials as recently as mid-May. Arreguin said he was shot down by the cost — a projected doubling of the annual per-unit fee to $65.

Berkeley’s reliance on self inspections is “only as good as the honesty of the people doing the reports,” Mayor Tom Bates said. The end result “is not too good,” he said, “but it is a question of having the resources to implement a different system. We don’t have the personnel.”

Some cities, neighboring Oakland among them, do not require routine annual inspections of rental units. Others, including San Francisco, Hayward, Antioch, Richmond and Pittsburg, run rental safety programs that range from scheduled inspections of all apartments to checks of a percentage of units in all rental buildings.

When they debated tougher rules in May, Berkeley officials studied how Sacramento and Seattle in particular could afford to maintain such rigorous inspection requirements, according to city records obtained by The Times under the California Public Records Act.

Berkeley’s self-certification program relies on building owners and managers to conduct their own inspections and no longer requires them to submit proof to the city. Two years after creating the program, Berkeley officials cited cost savings in dropping that requirement in 2003, along with the mandate that the city be notified of apartment vacancies to facilitate city inspections.

In 2009, Berkeley eliminated one of the four code inspector positions to save money.

According to an internal city report obtained by The Times, more than half of Berkeley renters said in a 2009 survey that their landlords had not conducted an annual inspection. Fewer than one out of five had seen the safety certification that landlords are required to provide renters.

City inspection files reviewed by The Times showed Berkeley code inspectors had never visited five of the city’s 12 largest apartment complexes, and had not been inside two others for more than a decade. The inspections conducted in the other buildings were limited to single apartments and were sometimes canceled after inspectors arrived weeks after complaining tenants had moved out.

The fatal balcony collapse occurred when a group of young people, most of them from Ireland, celebrated a 21st birthday at Library Gardens, a 176-unit complex build eight years ago. Library Gardens is owned by BlackRock, a New York investment firm, and managed by Charleston, S.C.- based Greystar.

Berkeley officials said Greystar was unable to provide proof that it had conducted city-required apartment inspections before the tragedy. On Friday, the city released copies of 2015 apartment inspection reports Greystar filed by the city’s July 1 deadline.

The management firm has since hired its own engineers to confirm the safety of the apartment complex. “The safety of our residents and their guests is our highest priority,” said Greystar spokeswoman Lindsay Andrews.

A private structural inspection report last fall provided by Greystar gave Library Gardens’ balcony supports a clean bill of health. It noted that settling had cracked its exterior and blown the water seals on 22 windows.

Berkeley’s sizzling real estate market and proximity to San Francisco have drawn major players in the last decade. City campaign finance reports show major apartment developers spent more than $250,000 last fall to defeat a zoning change that would have capped the height of downtown development. The measure did not address inspections.

Students in particular are vulnerable to rental hazards, said Ed Comeau, who runs Campus Firewatch, a national program that tracks campus fatalities and promotes education programs along with safety checks. “Inspections are slim to none in most campus towns,” Comeau said, “and let’s admit it, students are hard on the places they live in.”

In response to the deaths at Library Gardens, the city’s largest landlord, Chicago-based Equity Residential, is looking at its own balconies in Berkeley, a company spokesman said.

“While we have no reason to believe that the condition of any of our Berkeley balconies could result in the type of tragic incident that occurred [last] month, we have established a special inspection program, using visual inspections and invasive testing where appropriate, to assure that our Berkeley balconies are safe for their intended use,” spokesman Marty McKenna said in an email.

Mark Rhoades, who headed the city planning department when Library Gardens was built, said he believed dangers such as rotted balcony supports go beyond what city inspectors can find.

“The only way one could have known that the wood was failing, from what I have seen, would have been to get into and inspect the structure,” said Rhoades, who is now a development consultant for several apartment complex projects in Berkeley. “I don’t think the city or how it handled the plan check/inspection oversight is the issue.”

Former Berkeley Mayor Shirley Dean, who championed the 2001 rental inspection program when she was in office, has called for increased safety inspections and the public posting of the results.

“I am appalled with how the city is handling this,” she said. “They think this will blow over. Well, it won’t. We won’t let it.”

Twitter: @paigestjohn

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.