After a lengthy, costly federal investigation, ‘Shrimp Boy’ Chow finally goes on trial

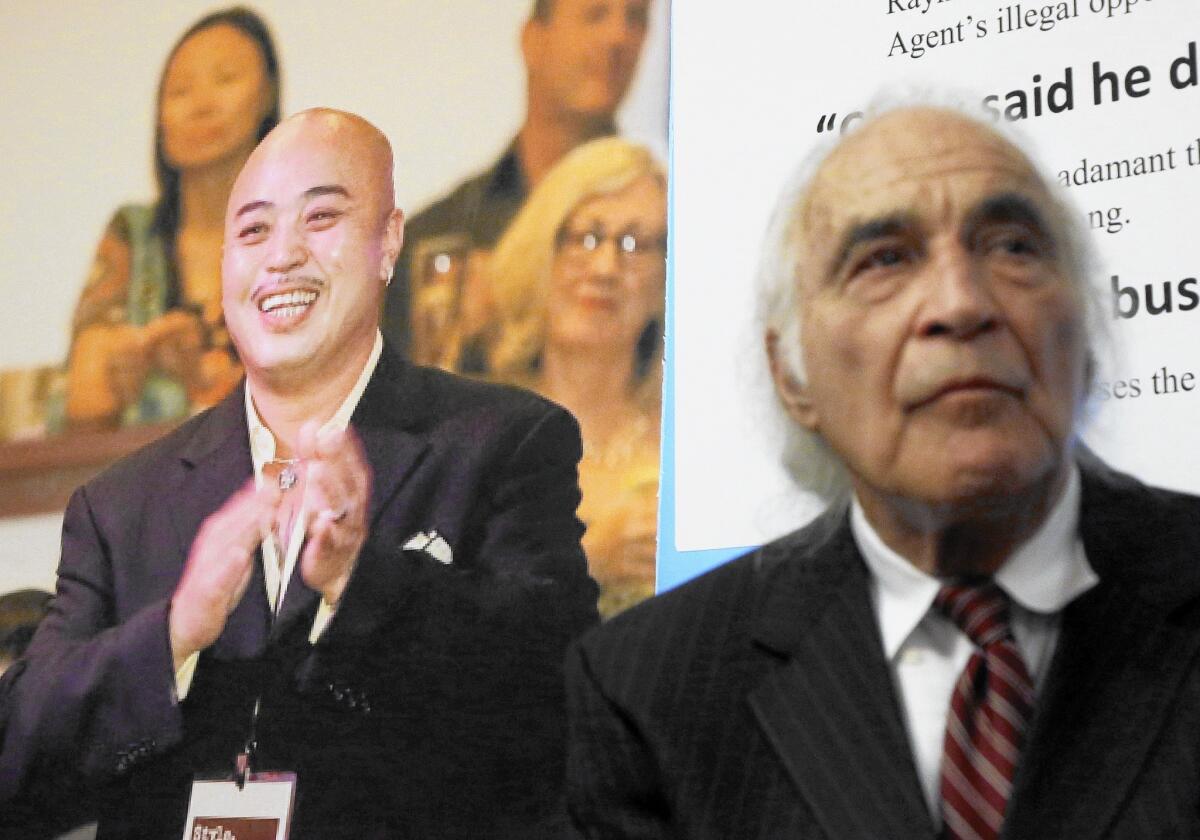

J. Tony Serra, right, is defending Raymond “Shrimp Boy” Chow, left, in his trial.

To federal investigators and prosecutors, Raymond “Shrimp Boy” Chow is and has always been a criminal.

Ever since he arrived in Chinatown from Hong Kong as a 16-year-old with swagger. Even as he testified for the government in exchange for a reduced prison sentence in an earlier racketeering case. And, most particularly, as he assumed the helm of the Ghee Kung Tong as its dragonhead.

Chow goes on trial here Monday in a federal courtroom after a lengthy investigation that cost millions in taxpayer dollars and swept up several dozen others — among them former state Sen. Leland Yee, who pleaded guilty to racketeering in July.

Chow, prosecutors concede, may have put on a decent act as gangster-turned-community-servant. But behind the scenes of the fraternal organization he controlled, they will argue, he was running a criminal enterprise that trafficked in weapons, contraband cigarettes and stolen liquor.

Last month, the U.S. attorney’s office upped the ante on the 140-count indictment, adding charges that the 55-year-old Chow had arranged the 2006 murder of his Ghee Kung Tong predecessor and conspired to kill another man who was shot to death in 2013 along with his wife.

The defense will tell a very different story — with the highly regarded, eccentric lawyer J. Tony Serra doing the telling.

It is a tale of a government investigation marred by the conduct of an undercover agent. The tactics of the man known mostly as UCE 4599 — his cover name was “Dave” — were so egregious, the defense maintains, that U.S. District Judge Charles R. Breyer should toss the case.

“History will show that this prosecution was the most shocking of all time,” Chow’s lawyers wrote in a motion for dismissal last week, one peppered with allegations they are sure to revisit at trial. “The only way to maintain the integrity of the federal judiciary in the Northern District is to acknowledge the severity of the government’s misconduct and dismiss the indictment against Raymond Chow.”

Serra, 80, a lifetime critic of government power known for his threadbare suits, has served federal time for tax evasion. He will be assisted by Curtis L. Briggs, another convicted criminal who was admitted to the state bar three years ago.

According to the motion to dismiss, the government’s errors began with a misinterpretation of the white suit Chow wore to the 2006 funeral of Alan Leung, the former Ghee Kung Tong dragonhead. (The FBI believed white to be a sign of Chow’s “rise to power,” the motion said. Chow, who has been charged with arranging Leung’s killing, contends he wore white as a Chinese symbol of respect.)

“Operation Whitesuit,” launched as an investigation into alleged criminal behavior by Chow, eventually snared 28 other defendants. Among them was Yee, who was connected to Chow through a political fundraiser.

The multi-year probe relied heavily on UCE 4599, who “after failing at legitimately snagging Chow, independently engaged in criminal acts with people who knew Raymond” and were drawn to the expensive dinners and drinks the agent showered on “all who would show up,” the defense motion said.

Transcripts of body wire recordings included in the document indicated that UCE 4599 had plied Chow with alcohol, then pressured him to commit crimes and accept cash. Affidavits submitted by the agent, the defense contends, mischaracterized the encounters.

One, for example, noted only that Chow had said “No, no, no” before taking an envelope full of cash and placing it in his sport coat. The defense, citing the recordings, painted a more detailed scene of the agent’s persistence.

“Ya, I’m drunk! No, no, no, no,” Chow said as “Dave” pressed the envelope on him. “No, I’m, I’m good. I’m good,” Chow continued.

In another instance, Chow said he was “hella drunk.” As he tried to forcibly return another envelope of cash, the agent told him: “Stop. Stop.”

According to the prosecution, Chow merely pretended to keep his hands clean while making the introductions necessary for his criminal enterprises to flourish. Transcripts included in the defense motion, however, depicted Chow repeatedly attempting to distance himself from illegal activity.

“Listen, I’m just helping them. You know, but you’re helping me,” UCE 4599 said.

“No,” Chow replied. “I did not help you! I don’t even know what you guys doing!’”

Serra and Briggs are not seeking to prove entrapment — a factual defense that “almost never works” in federal court, said Robert Weisberg, a Stanford University law professor and founder of the law school’s criminal justice center.

Unlike in some state courts, Weisberg said, a federal entrapment claim would necessitate the defense showing that its client had few or no proclivities to commit the crimes in question. “The fact that Shrimp Boy is a many-times felon … makes him look not as pure as the driven snow,” Weisberg said.

By alleging “outrageous government conduct,” on the other hand, the defense will be able to focus on that rather than Chow’s history. Breyer cannot instruct the jury to consider the conduct as a potential reason to acquit — as he could with an entrapment defense. But the jury nevertheless might be influenced by the material, Weisberg said. The defense also could ask Breyer to step in at a later point in the proceedings and issue an acquittal on his own. The question he must ponder, Weisberg said, will be: “Is this government conduct so egregious that it would cause even an innocent guy to cave?”

A half-dozen of Chow’s co-defendants have pleaded guilty, and two are expected to testify that they heard Chow order the killings. Another witness serving prison time in an unrelated case is set to testify to driving Chow and a “henchman” to Leung’s office on the night of his slaying — and later watching them disassemble guns and toss them into the bay.

The defense has moved to exclude testimony from those witnesses as unreliable; further, they intend to argue that none of the criminal concepts came from Chow.

The government, the defense motion stated, supplied Chow “with all the money in the money-laundering operation, with all of the alcohol in what would become an illegal alcohol operation, and with all the cigarettes in the cigarette operation.” And the ideas for all those schemes “originated with UCE 4599.”

A spokesman for the U.S. attorney said the office does not comment on active cases; prosecutors as of Friday had filed no response to the defense motion.

Twitter: @leeromney

ALSO

A pair of skimmers do clean sweeps of Oceanside’s harbor

UFO scares are the price we pay for secret missile tests, expert says

Detectives say dead youth in East L.A. may have accidentally shot himself

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.