Op-Ed: The merits of universal voter registration

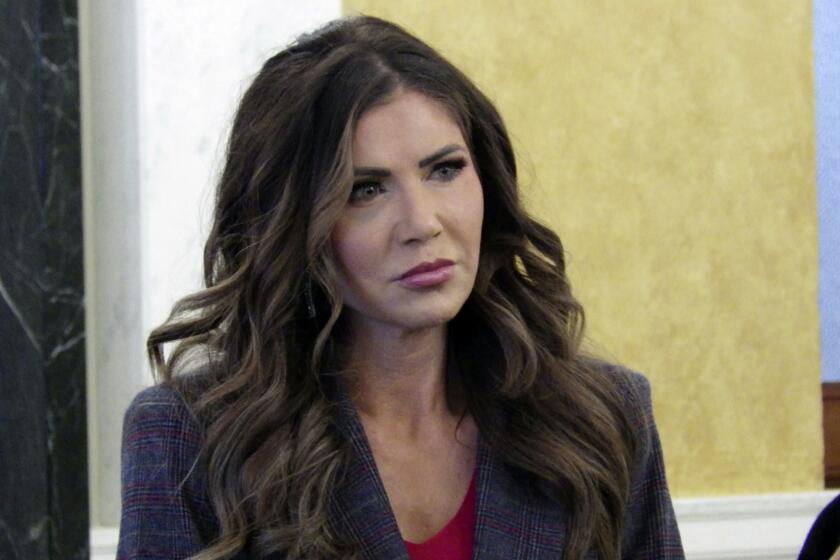

Oregon Gov. Kate Brown smiles after signing an automatic voter registration bill on March 16 in Salem, Ore.

Why force citizens to register in order to vote?

Secretary of State Alex Padilla raised that question this year when he proposed a law that would automatically register every eligible voter with a driver’s license. “One of the biggest barriers to citizen participation is the voter registration process,” he said. “A new, enhanced California motor-voter law would strengthen our democracy.”

Many Democrats in Sacramento — and beyond — agree.

Oregon’s governor recently signed an automatic voter registration bill.

And this month, Hillary Rodham Clinton called for automatic, universal voter registration as well as a 20-day early voting window. She also accused her Republican rivals of “a sweeping effort to disempower and disenfranchise people of color, poor people and young people from one end of our country to the other.”

It is generally thought that automatic voter registration would benefit Democrats and hurt Republicans. So it’s safe to assume that politicians on both sides of the aisle are biased by that knowledge.

Still, it’s possible to set partisan considerations aside and have an apolitical, substantive debate on the issue.

Conservative pundit Dan Foster favors allowing ex-convicts to vote, even though doing so would harm the prospects of Republicans. But while he favors a near-universal franchise, he is wary of making voter participation easier than it already is.

“The need to register to vote is just about the most modest restriction on ballot access I can think of,” he wrote recently, “which is why it works so well as a democratic filter: It improves democratic hygiene because the people who can’t be bothered to register (as opposed to those who refuse to vote as a means of protest) are, except in unusual cases, civic idiots. If you want an idea of what political discourse looks like when you so dramatically lower the burden of participation that civic idiots elect to join the fray, I give you the Internet.”

Progressive journalist Jamelle Bouie agrees that democracy requires informed citizens and that increasing the pool might make the average voter less informed, at least in the short term. But he has argued that “like any task, you get better at voting the more often you do it. Relatively uninformed voters in one election might become highly informed voters a few cycles later.”

Although I see no definitive way to resolve their disagreement, I find myself favoring universal voter registration.

That is partly because I don’t think that filling out government paperwork is a reliable proxy for who is an informed voter and who is a civic idiot. Nor do I expect that civic idiots will start turning out in large numbers on election day. The sort of person who’s too apathetic to register is probably also too apathetic to cast a ballot.

And let’s not pretend that a civic idiot on one subject is necessarily a civic idiot on another.

A citizen might not register to vote because she knows she’s unfamiliar with national or state politics writ large. Yet that same person might have strong opinions and expertise on the sort of issue that ends up on a ballot measure. If she didn’t file her paperwork in time for the referendum, that would amount to a civic loss — especially in a place such as California, which has an element of direct democracy built into its political system.

Mostly, however, I favor automatic registration because modern political campaigns increasingly target only those who are already on the voter rolls.

In a bygone era, political information was largely addressed to general audiences. Antiwar candidates or small-government candidates tried to spread their ideas as widely as possible, using TV and radio ads and scattered public appearances. And some of the people who encountered these ideas would be spurred to civic participation.

Today, candidates and advocacy organizations are getting better and better at directing their messages exclusively at registered voters. For example, Facebook’s advertising guidelines for political operatives mention registered voters as one of the demographics that can be targeted with third-party data.

Over time, this could create a civic divide unlike any in our history. Lack of participation would perpetuate itself.

Take a person who doesn’t register at age 18, when most people exhibit low levels of civic interest.

In the old days, he would have experienced subsequent campaigns much like his peers who registered at the first opportunity; over time, he would have come across a great deal of — possibly engaging — political information and commentary.

These days, those who register to vote at the first opportunity and those who do not are likely to find a much higher degree of variance in their exposure to campaign issues.

At the local, state and federal levels, registered voters will be awash in highly targeted pitches and get-out-the-vote efforts, while those who don’t register will be almost totally ignored.

Doesn’t that isolation from the democratic process risk creating civic idiocy over time? I think so. And that risk outweighs the benefits of conserving needless registration paperwork.

Conor Friedersdorf is a staff writer at the Atlantic and founding editor of the Best of Journalism online newsletter.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.