Op-Ed: Let’s compare Eric Garcetti and Bill de Blasio

Los Angeles can lord it over New York even without pointing to the paradisal weather. Yes, the traffic is still terrible, and the basketball is only getting worse. Angelenos, however, have Mayor Eric Garcetti, an embodiment of pragmatic politics. New Yorkers have Mayor Bill de Blasio, an ideologue driven by a self-serving fervor who eats his pizza with knife and fork.

The controlling image of De Blasio’s first campaign, in 2013, was “a tale of two cities,” one for the rich, the other for the poor. At his inauguration, he vowed to lead the “march toward a fairer, more just, more progressive place” by striking “a new progressive direction” that would deviate from the fiercely technocratic centrism of his predecessor, Michael Bloomberg.

On Monday, De Blasio was inaugurated to his second term. But four years in, you’d be forgiven for missing the signs of revolution on Manhattan’s streets. That’s because, like a certain other New Yorker recently elected to higher office, De Blasio likes to galvanize his base with electric rhetoric that disguises a surprising comfort with the status quo.

De Blasio does have a few accomplishments to boast about, the most notable among them being universal pre-kindergarten, now attended by about 70,000 children. Free, early schooling sure sounds nice, and is surely appreciated by the city’s less-than-wealthy families. But the gains of pre-kindergarten dissipate unless followed by a strong K-12 education, and De Blasio has shown no willingness to confront the city’s powerful teachers union.

De Blasio likes to galvanize his base with electric rhetoric that disguises a surprising comfort with the status quo.

He has been dismayingly tentative in challenging the more powerful — and more pugnacious — police unions. More than three years after the killing of Eric Garner, an African American resident of Staten Island, not a single police officer in New York has received implicit bias training.

De Blasio has promised to create or preserve 200,000 affordable housing units, and though his administration has either created or maintained 77,000 such apartments, his plans to rezone large parts of the city have been meet by ferocious community opposition. Much of his first term was spent fending off investigations into improper fundraising. The homeless population is growing. The subways are a mess. And because De Blasio’s sanctimonious tone has alienated New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo, he can’t ask Albany for help.

Because it’s almost impossible to challenge a Democratic incumbent in New York, De Blasio won reelection last fall. At his swearing-in, he declared the beginning of “a new progressive era,” almost exactly as he had four years before. He also alluded to doing work that would be felt “beyond our borders.” He plainly wants to run for president, and hopes New Yorkers will be patient as he travels to Iowa and New Hampshire.

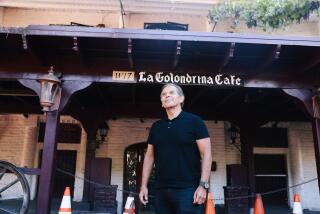

New York is the nation’s largest and arguably most important city, but Los Angeles is the most complex. Keeping the place from devolving into chaos is no easy task — and plenty of City Hall’s previous occupants have failed. Garcetti doesn’t pretend that Los Angeles is ever going to be a noiselessly efficient Scandinavian city on the order of Helsinki, but he radiates the cool competence of a manager confident in both government and those who are governed.

Garcetti may be considering a run too, but he has never tried to place himself at the head of a revolutionary vanguard, or even to appear all that interesting. Garcetti understands that politics is the art of the possible. It is about making people’s lives better, sometimes with grand gestures, but often with little ones. That has led to criticism that Garcetti is overly cautious. Fair enough. But he has persuaded Los Angeles — its citizens, its community leaders, its elected officials — to pursue his vision of sound incrementalism to benefit the public good.

The Mobility 2035 plan would radically remake Los Angeles. Some of the already-implemented fixes are small, like the tables carved out of what had formerly been a lane of traffic in front of Grand Central Market. Protected bike lanes and faster bus service, however, could be significant victories against the car culture that has dominated Los Angeles for decades.

Garcetti also won approval for a proposal to have real estate developers pay “linkage fees,” a kind of tax that will go toward building affordable housing. He has also pushed on multiple fronts to solve the homeless crisis — an issue that elicits Garcetti’s ambition. “We are not here to address homelessness, or manage homelessness, or reduce homelessness. We are here to end homelessness once and for all,” he said last year.

While homelessness reveals Garcetti’s aspirations, it brings out De Blasio’s frustration with reality, in all its complexity and unruliness — and, ultimately, his defeatism. Last year, he said of the homeless crisis: “I today cannot see an end.” Far too often, his idealism has led to seething complacency, to apportioning blame instead of finding solutions opponents can countenance.

Los Angeles faces immense problems: congestion, homeless encampments, perpetually failing schools. A revolution of some kind may seem tempting. But as De Blasio has shown, grandiose promises are almost always delusive. And when they aren’t, you end up with Robespierre manning the guillotine in the middle of Paris. I might just stick with the guy paving potholes.

Alexander Nazaryan is a senior writer at Newsweek covering national politics.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion or Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.