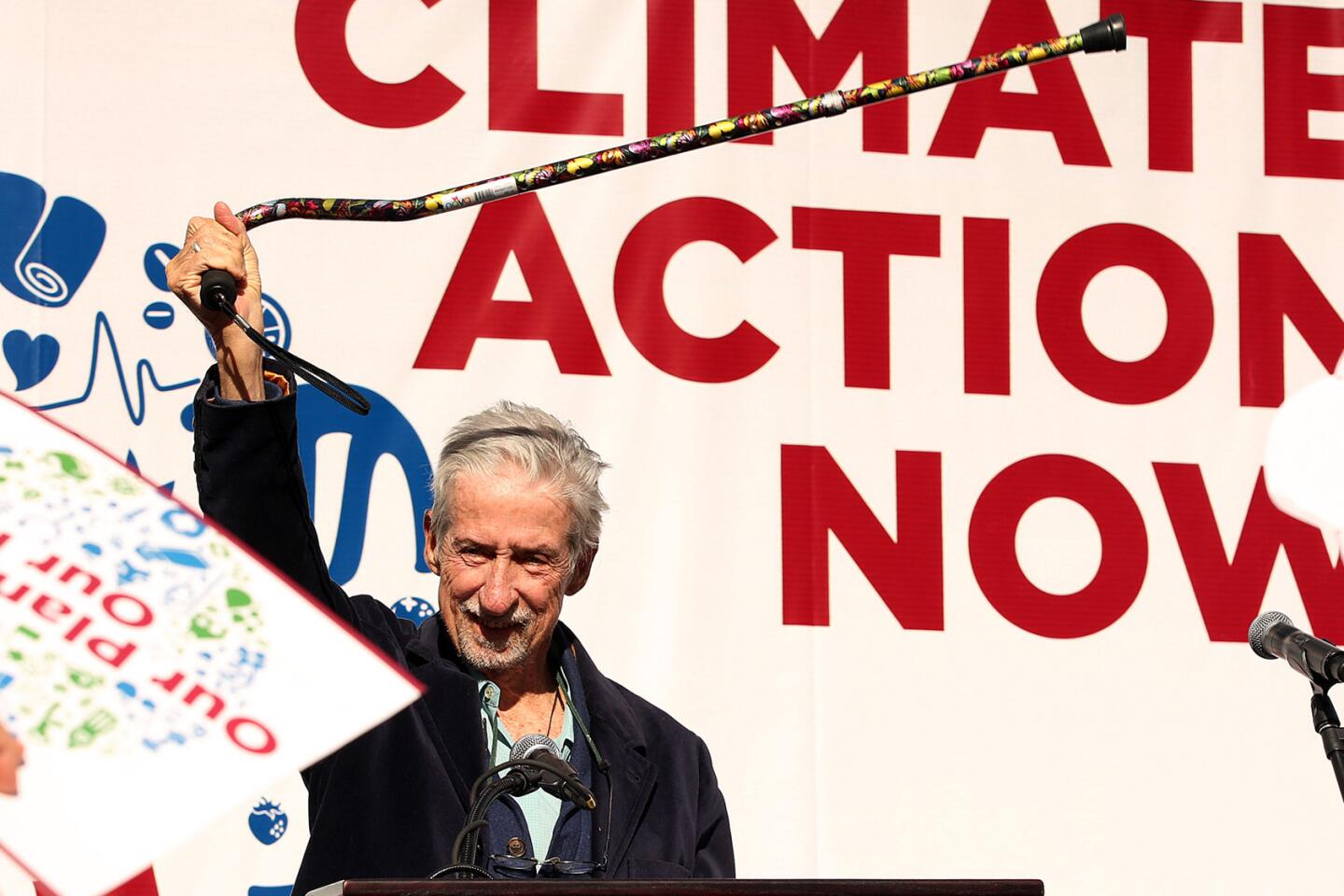

From the Archives: Tom Hayden is serious about running for governor. So why is he having fun?

Editor’s note: Tom Hayden, one of the nation’s best-known champion of liberal causes, has died in Santa Monica at the age of 76. Hayden served a total of 18 years in the California Assembly and state Senate, mounting a bid for governor in 1994. This article first appeared in the Los Angeles Times on May 22, 1994.

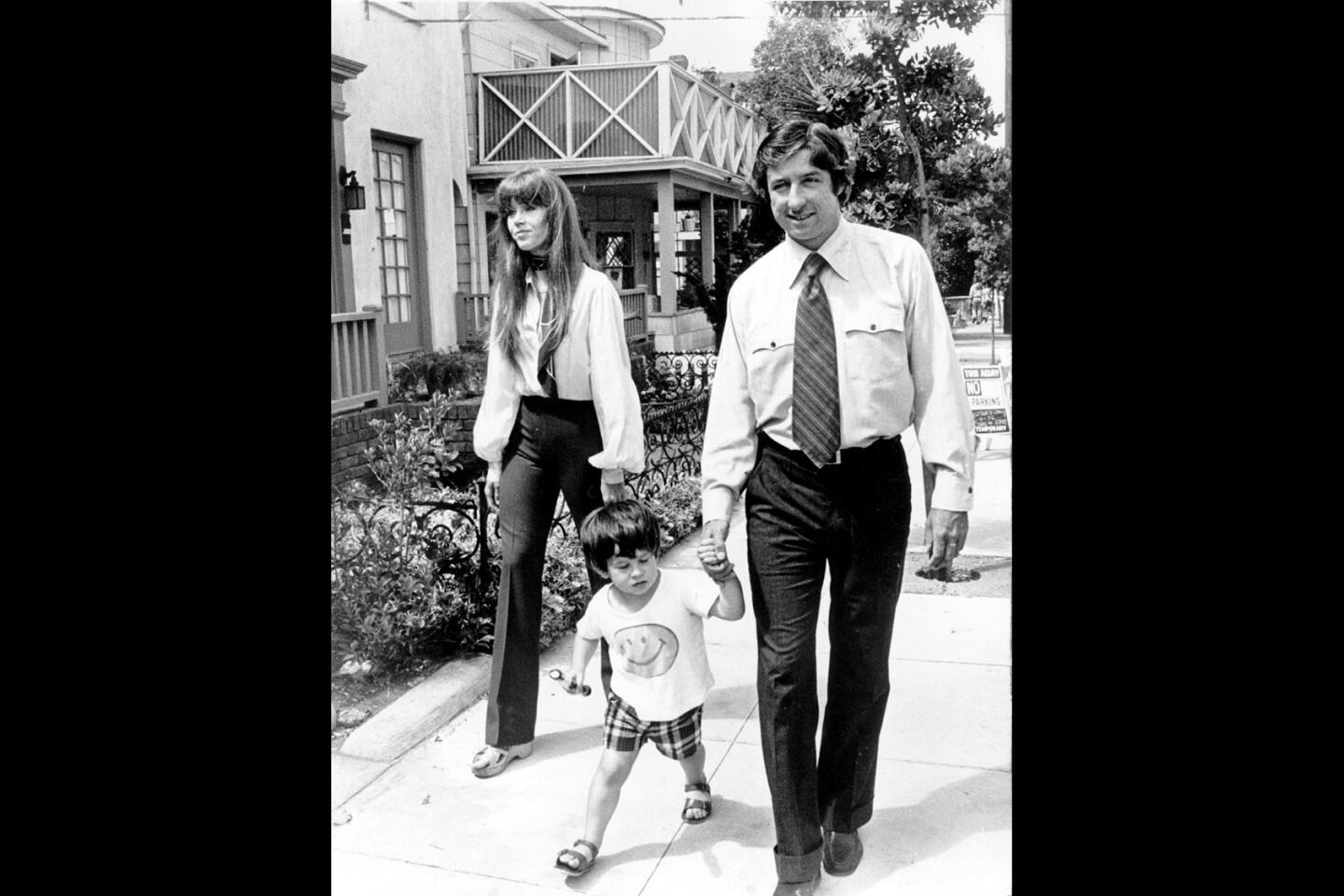

This is serious stuff, this business of running for governor. So why is Tom Hayden — the activist with the angry edge, the man who thwarted the Establishment during the Vietnam War, the non-glamour half of Jane and Tom, the man whose sober warnings of California crises have been uttered regularly for years — why is he having fun?

On the patio of a Santa Monica cafe, where the next table’s raucous rendition of “Happy Birthday” has just ruined part of Hayden’s interview with a local television station, the candidate launches into a serious discussion of his place in the political landscape. Suddenly, he veers off.

“There was this guy in San Francisco. We were asking him what he knew about Hayden,” the state senator says. “He said: ‘He was married to that woman who channels — what’s her name? — Shirley MacLaine.’ ”

Jane Fonda’s ex-husband let loose a well-timed grin. “Wwweeellll, it’s a start.”

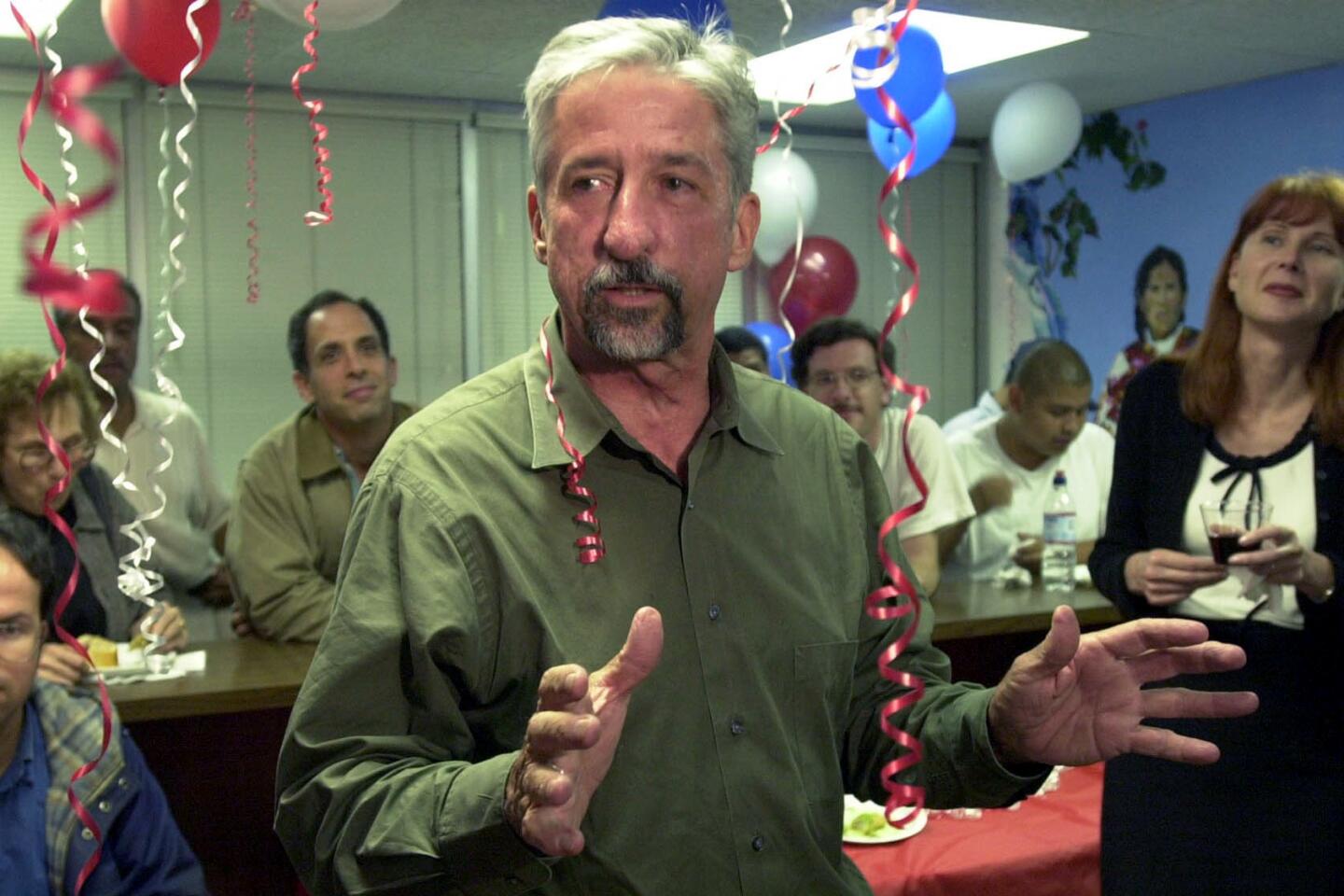

These are the final weeks of the gubernatorial primary campaign, a time when humor has abandoned most candidates. It is a time when the answers to every question come out rote, memorized from briefing books or memos, when the sheer physical drain of a long campaign starts to wear out even the most hardy of characters.

And into this increasingly tense race for governor has come the loquacious Hayden, the state’s least likely purveyor of the politics of joy, having a darn good time slashing away at big-time politics even as he seeks to become the state’s big-time politician. His message is simple: The political system stinks, so let’s reform it.

Sure, he has little chance of winning, say the seers and pundits, mindful of the huge advantages held by Democratic front-runner Kathleen Brown and a second major candidate, John Garamendi. But that would be measuring Hayden’s campaign by conventional standards and that, in the words of President Richard Nixon, whom Hayden battled in the streets, would be wrong.

Hayden wants to win, no doubt about that. In his ever-so-equivocal style, he offers his reasoning: “I’m as frail and flawed as anybody else, but I’ve seen the people who have been governor and I think I can do that job.”

But this is about more than winning. This is about Hayden fulfilling his destiny — spiritual and political. It is about Hayden becoming more than the four words he says capture his image among California voters: ‘60s radical, Jane Fonda. He is driving this vehicle of self-realization, and everyone else is invited along for the ride.

**

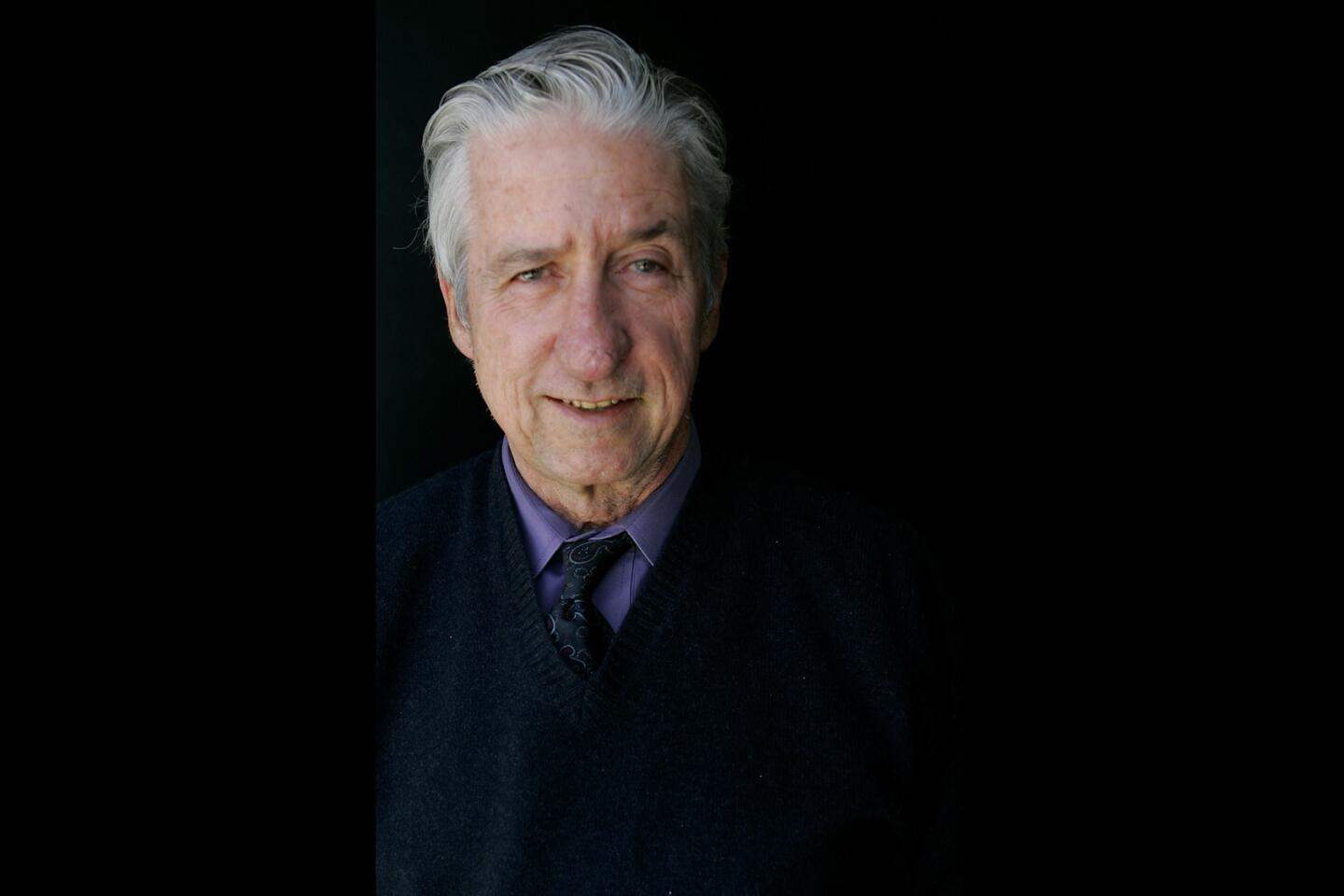

He is a California original, right down to the fact that he was born elsewhere and has remade himself a few times over: From the war protester to the legislator, from the man who questioned the state Senate’s necktie rule to the guy in the nice midnight blue linen suit and tie that matches, wending his way from interview to interview on a recent campaign day.

Part of Hayden’s rogue charm is that he plays all the parts at the same time with chameleon-like ease. Put former Gov. Edmund G. (Jerry) Brown Jr., who shares Hayden’s outsider, save the planet views, into a room with the state’s political aristocracy and he can look physically ill. Hayden, by contrast, is one of them.

He has even come to look like one of them — at 54, his hair is graying distinctively around the temples. But he will never sound like them, not with the things that keep coming out of his mouth.

What other candidate, when asked why he is running for governor, says that the Jan. 17 earthquake jolted him into questioning his “time on earth”?

What other candidate, asked his political profile, says earnestly: “I’m Jeffersonian in terms of democracy, I’m Thoreau in terms of environment, and Crazy Horse in terms of social movements”?

What other candidate circulates as the mailer for his $94-or-less fundraiser a picture of himself being beaten to the ground during a 1961 voter registration drive in Mississippi — complete with the line: “You can’t keep a good man down”?

And he has a talent for making it all sound, well, reasonable.

Ask him if he is still the rebel liberal, an appellation bestowed upon him by this newspaper, and Hayden will heartily agree.

“I hope so. What other honorable path is there?” he says, as if mystified by the question. “We live in a city with 105 square miles of poverty. . . . We have the most poisoned air in the United States. We’ve lost 300,000 to 400,000 jobs in the past three to four years just in this district. If you don’t rebel against this fate, God help you. What’s the alternative?”

Still, Hayden has heard all the criticisms — that by running for governor he is ego-tripping or, worse in the eyes of Democrats, possibly harming his party’s candidates. He doesn’t buy it.

“I’m not really running against anybody,” he said. “I’m running against the established order of things and I think Kathleen and John kind of reflect established thinking. . . . You’re trying to win but it’s not like you’re trying to annihilate the other person.”

His anti-Establishment attitude started early. “I was told it was adolescent rebellion 40 years ago,” he says wryly. “I’ve finally come to the conclusion that sure, some of it’s hormonal, but that doesn’t explain the lifelong nature of it.”

He is comfortable enough in the Establishment, however, to have been part of it for years. In 1982, he won election to the Assembly; 10 years later he moved up to the Senate in a hugely expensive and nasty race funded largely by his Fonda divorce settlement.

This campaign, however, is hardly the juggernaut. It has, by the count of campaign manager Duane Peterson, a staff of nine people. The campaign on which Peterson worked four years ago — Atty. Gen. John K. Van de Kamp’s bid for governor — had nine people just on its fundraising staff, and that for a campaign which nearly ran out of money before the primary.

“It helps when the candidate doubles as research director, speech writer and chief strategist,” Peterson said.

The Southern California headquarters are in an office in back of Hayden’s Santa Monica home, the only one on its fashionable block where the front lawn has been torn up in favor of a rebellious thatch of wildflowers and a discreet compost bin. Hayden is his campaign’s biggest donor — he expects to spend hundreds of thousands of dollars before it is over and, in keeping with his reform strategy, will accept contributions of $94 or less to pay back his personal loans. It leaves the operation “lean and mean,” Peterson said.

That much can be gleaned from Hayden’s occasional obsessions about things that a more conventional candidate would never have to consider — for example, how to get the campaign a few cars so volunteers do not have to take the bus on their voter forays.

Careening down the Santa Monica Freeway from one appearance to the next, he moaned via cellular phone to Peterson in Sacramento.

“We need help from our criminal supporters,” he says. “Go to the chop shop and get a car, for God’s sake.”

Honest, he was kidding.

**

Hayden’s good humor, relative to the other candidates, should not be mistaken for a laissez-faire attitude about the governorship. About this, he is deadly serious. And although his chances of winning are slight, he has been given high marks by observers for his emphasis on the issues.

Rarely, unless pressed, will Hayden take off on a tirade about his opponents. He saves his powder for the system. Much of his time is spent attacking the gravy train that links the state’s lobbyists and its politicians. His campaign video, which is being run on cable stations statewide, underscored that with the presence of former legislator Alan Robbins, who served prison time for taking bribes.

“The modern campaign has become a kind of sport in which you have a cell phone on your ear and you’re asking for large sums of money from special interest groups to give to people who produce television images of you and you can rest content that many more people will see those television spots than will ever hear an interview, a discussion or read the Los Angeles Times,” Hayden says. “So it’s become more about merchandising and less about anything that’s meaningful.”

His solution is a $250 limit on campaign contributions, removing tax breaks for lobbyists and enforcing sanctions for political corruption.

He also was first among the candidates to release a budget proposal, although his was spare on some important details. In general, he favors closing $3 billion in tax loopholes, trimming the state’s bureaucracy by $1 billion and refusing to fund the recently approved “three strikes” legislation, which he considers fiscally reckless. He has vowed to cut student fees at the state’s universities and colleges, spend more money on seismic safety and create an electric car industry in Southern California.

Crime, he says, could be attacked by creating police and teacher corps made up of thousands of college students.

Driving through Hollywood, where graffiti mark gangland territories, Hayden says he considers the state’s fixation with crime a “real problem.”

“The whole world is in spasms that we’re not immune from,” he says. “Religious disputes, racial grievances, poverty, drugs. It’s apocalyptic out there.”

**

Any politician is ambitious. In Hayden’s campaign meanderings, there is also something else — a sense that he is captive to a need for personal momentum, a demand to move from one psychic place to another. Ask him and he will agree. The campaign is only one manifestation.

“I’m also restless about trying to get to the bottom of things and be spiritually grounded and make and get a better understanding of what is going on,” he says. “It’s one thing to say the system doesn’t work and all the formulas for full employment and health care are brain-dead or tired or old ideas. But to really try to understand crime, drugs, despair, unemployment and put it into context — I’m a seeker.”

Spirituality and the pacifism that it suggests seem far from the Hayden of old. Indeed, the old rage seems to have tempered.

“I’ve begun to learn that while rage and hate are natural impulses, they are not sustaining,” he said. “I don’t think I would have survived this long in movements or politics if I was fueled by the same level of anger that I was fueled by in the ‘60s.”

Peterson, Hayden’s campaign manager and longtime aide, says the candidate is more centered than in the past, in part because of his marriage in August to actress Barbara Williams and his more prominent role in the state Senate.

“And running statewide is exciting,” Peterson said. “California is a fantastic place and having an excuse and/or being forced to travel to the broad reaches is fun.”

For Hayden, the campaign for governor is not only an opportunity to seek deep answers but also a chance to remake his image, which seems to have stalled a generation ago. It has been, after all, 26 years since the height of his student radical days; he and Fonda split five years ago. Still, he is well aware that most Californians think of him in those distant terms.

“For a long time, I was feeling sort of upset that one’s life could come down to such labels,” he said.

But he takes heart from the symbolism in his favorite book, Hermann Hesse’s “Siddhartha.”

Any other candidate might shy away from such symbolic comparisons. Hayden openly makes them.

“This is the role of somebody who wants enlightenment and wants meaning but understands they can’t have it without it happening for everyone at the same time,” he says, speaking about Siddhartha and himself. “The quest for your own discovery of meaning is tied in with the need for everybody to have meaning.”

Twitter: @cathleendecker

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.