Hard work has brought Albert Pujols to the brink of 3,000 hits

When Tommy John beat the Angels for his 268th victory in May 1987, the left-hander, then a 44-year-old with the New York Yankees, was asked if he had a burning desire to win 300 games.

“The only thing that burns inside of me,” John said, “is Szechuan cooking.”

Such words would never be uttered by Albert Pujols, the Angels slugger with a seemingly endless reservoir of drive and determination and a work ethic that borders on maniacal — a combination that has helped push Pujols to the brink of another historic milestone.

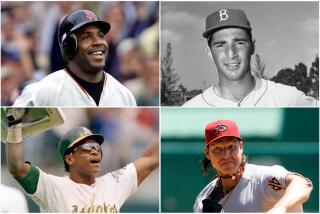

With four more hits, Pujols, 38, will become the 32nd major leaguer to reach the 3,000-hit mark, and only the fourth with at least 3,000 hits and 600 home runs, joining Hank Aaron, Willie Mays and Alex Rodriguez.

From his childhood in the Dominican Republic to his high school and junior college years in Missouri, his 11-year reign as baseball’s best right-handed hitter in St. Louis and his seven years in Anaheim, there have been no shortcuts on the path to baseball’s Hall of Fame.

“The one thing that is very understated about Albert is the sense of how hard he actually works at hitting, the studying of the pitchers, the actual time he spends in the cage,” said David Eckstein, the former Angels shortstop who was a teammate of Pujols in St. Louis from 2005 to 2007.

“When the best player on your team is the hardest worker, it helps the club win … so when you take that work ethic and you add it to someone who has the skill set he has, the eyesight he has, the hand-eye coordination he has with hitting, that’s why he’s closing in on 3,000 hits and 600 home runs.”

Eckstein played with Pujols when the latter was “The Machine,” his nickname during a career with the Cardinals (2001-11) in which he hit .328 with a 1.037 on-base-plus-slugging percentage, averaged 40 homers and 120 RBIs a season and won three most valuable player awards and two World Series titles.

A series of leg and foot injuries and age have reduced Pujols to a .261 hitter with a .775 OPS with the Angels, but he still produced three 30-homer seasons and four 100-RBI seasons in the first six years of a 10-year, $240-million contract.

Pujols, who notched career hit No. 2,996 against the Yankees on Sunday and is batting .248 with five homers and 14 RBIs, has never veered from the work habits that made him one of baseball’s most feared sluggers.

“He works on his swing every day — he never takes a day off,” Angels center fielder Mike Trout said. “He’s been up here for so long, 17, 18 years, and he still keeps the same routine every single day, just coming in and working hard.”

Pujols is a creature of habit when it comes to preparing for a game. He performs about a dozen hitting-off-a-tee drills and an extensive soft-toss ritual before he steps into the batting cage. He has no interest in trying to hit balls 500 feet during batting practice.

“He swings the bat with a purpose,” Eckstein said. “You won’t see Albert launching balls in BP. He focuses on line drives, going gap-to-gap, using the whole field. If you learn how to take the bat to the ball with a more consistent, level swing, that’s when the doubles soar and the home runs show up.”

Eckstein was no stranger to hard work. What he lacked in size and tools he made up for with grit, transforming himself from a waiver-wire claim to a leadoff hitter for the World Series-winning Angels in 2002 and Cardinals in 2006. But Pujols still rubbed off on Eckstein in other ways.

“He had a keen sense of being able to lock in on pitchers and see the little things that might tip off what they’re going to throw,” Eckstein said. “He’d point it out to me on video and live. ‘When you see this, this is what they’re gonna throw.’ Most pitchers, without even knowing, have certain habits.”

New Angels second baseman Ian Kinsler, in his first season with Pujols, is already reaping similar benefits.

“Watching him get prepared for that certain pitcher, what his approach is gonna be, talking to him at-bat to at-bat … it’s a lot of fun to watch guys of that caliber,” Kinsler said. “For me, when you’re in your 16th or 17th year in the big leagues and your focus is still at an elite level, I think that’s what is most impressive.”

Kinsler, a former Rangers and Tigers infielder, played against Pujols for six years and saw how injuries slowed him in the batter’s box and especially on the bases.

He was impressed when Pujols, listed as 6-foot-3 and 240 pounds, reported to camp 15 to 20 pounds lighter this spring after adjusting his winter workout regimen. That has allowed Pujols, relegated to designated hitter the last two seasons, to make 15 starts at first base already this season.

“That tells me he doesn’t like being embarrassed,” Kinsler said. “A lot of the work we put in, the things we do to prepare ourselves, is because we’re all competitive people, we don’t like to be embarrassed.

“Albert still has three more years on his contract, and he wants to hold true to that. He’s that type of person. No one likes to go out there and look bad, or to look unfit, whatever the case may be. It’s a pride thing.”

For all of Pujols’ power, he has never struck out more than 93 times in a season, and he’s had 10 seasons with 70 strikeouts or less. Rodriguez, who had 3,115 hits and 696 homers, struck out 100 times or more in 14 of his 18 full seasons.

“Albert is such an anomaly in so many ways,” said Rodriguez, who was in Anaheim for ESPN’s Sunday night Angels-Yankees telecast. “When you think about the combination of power and contact, it’s a lost art in today’s game.”

Could that make Pujols the last member of the 3,000-hit, 600-homer club?

“The game is being appraised and rewarded differently,” Rodriguez said. “People are talking less about hits, RBIs and runs scored and more about home runs, strikeouts, walks and launch angles. So, for that reason, it will be hard to find more of that combination of power and contact.”

Twitter: @MikeDiGiovanna

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.