A teacher loves his job -- and is so frustrated he might walk away

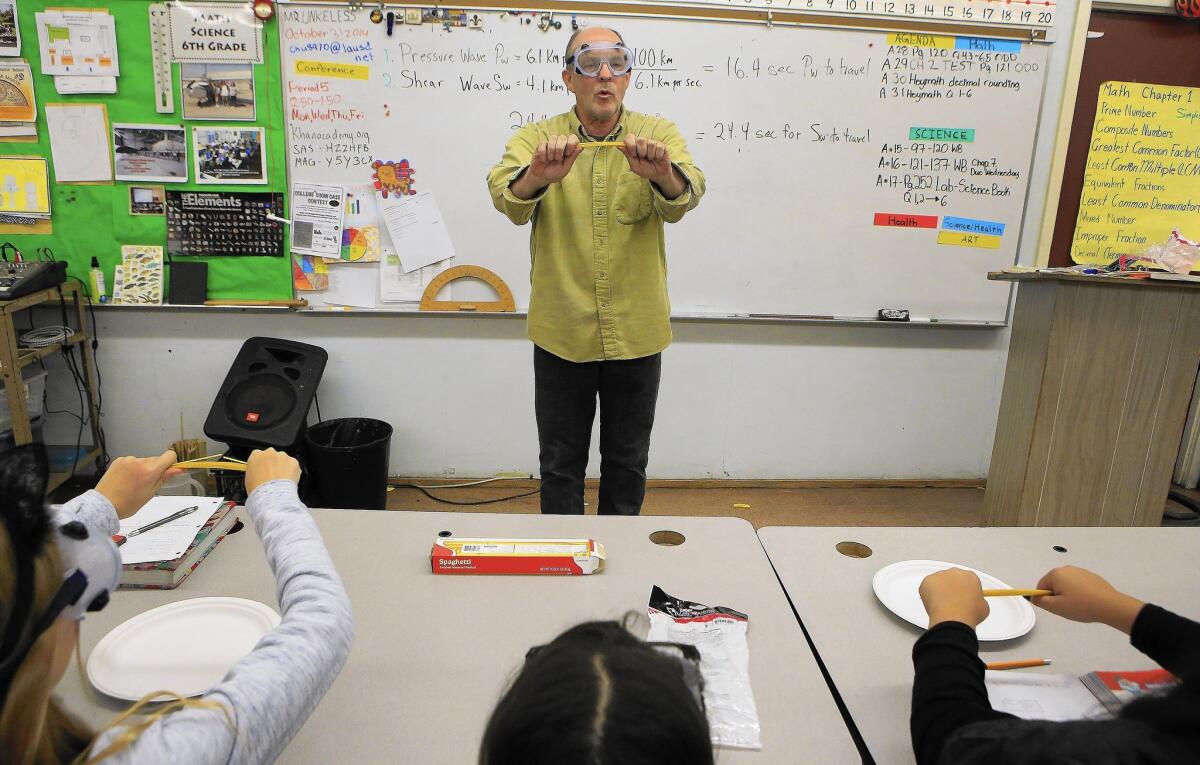

Charlie Unkeless has the smile of a man who loves what he’s doing, and his sixth-grade students are having a good time too. Who wouldn’t, when the teacher is using a Slinky and a pound of spaghetti to demonstrate what happens when an earthquake hits?

The math and science magnet teacher at John Burroughs Middle School holds one end of the Slinky on a table, and a student stands 15 feet away holding the other end. Unkeless gives the Slinky a shake, and a quiver spirals the length of the toy, mimicking a seismic wave.

Unkeless then has his class compute how long it would take to feel the ground shake if you’re standing 100 kilometers from the epicenter. Then he’s on to bending spaghetti to illustrate the elastic nature of the Earth’s crust, and students are wearing goggles in case the pasta goes flying.

Charlie Unkeless, now in his early 60s, has worked as a jazz musician, animator and lighting designer, coming to teaching only 12 years ago. But this, he said, “is the most rewarding and important job I have ever had.”

So why, despite his love of teaching, is he so frustrated that he might soon give it up?

That’s what I went to talk to Unkeless about last week, and I’ll get to that in a moment.

But first let me say that when you write about public education, it doesn’t seem to matter what you say —you’re guaranteed to come under fire. Discourse is so divisive and partisan, it’s like covering Congress, or covering a war without end.

When I wrote about all the missteps by now-departed L.A. Unified Supt. John Deasy, critics wondered why I didn’t lay more blame for his failures on the teachers union. And when I wrote that United Teachers Los Angeles is militantly inflexible on many issues, teachers screamed that I was scapegoating them and playing the stooge for billionaire “reformers” out to privatize public education.

I decided to get out of the crossfire and into the classroom.

What’s it like to teach today, with so many distractions and raging philosophical battles?

I decided to visit Unkeless because he struck me as a thoughtful guy — a strong believer in his union despite a few points of disagreement.

He thinks teachers are due a bump in pay after several years without a raise, but he doesn’t want to go on strike, and he’d prefer that his union focus more on the day-to-day needs of teachers than on the broad issues of social justice UTLA has become enmeshed in.

And, though he appreciates the protections of tenure, he thinks teachers who aren’t cut out for the job make life harder for students and other teachers.

Is he glad Deasy is gone?

“Absolutely,” said Unkeless, who believes the superintendent tried to ram through his agenda with no teacher input, and spent millions on questionable technology while arts instruction got whacked and schools fell deeper into disrepair. And don’t get him started on the disastrous rollout of the balky new multimillion-dollar student-tracking system.

The new Common Core standards have their advantages, said Unkeless, and one of them is the opportunity to expand the Socratic method of talking through problems. But, if discourse is considered a virtue, then why are those driving education policy interested only in a one-way discussion?

And though he loves walking into a classroom filled with kids whose families come from all over the world, he’s put off by our failure to adequately invest in their potential. Unkeless used to have 32 students per class, but now 37 are packed into his classroom, situated in a tired old bungalow, and it’s harder than ever to address the individual needs of students with a broad range of skill levels.

As for supplies and materials, he keeps digging deeper into his own pockets.

The scanner and movie projector are his own, and he uses his wife’s laptop to run the projector. He borrowed and restored his mother’s computer for class use. He finally got a copy machine after writing a grant proposal, but he has to do the maintenance on it himself.

He buys everything from paper to soap to tissues. He built a P.A. system so that shy students with tiny voices could speak into a microphone. He rigged an old electric drill to power an earthquake simulation machine and uses it to shake up miniature buildings constructed by his students, and he recorded the demonstration for YouTube.

And how have his efforts and those of so many other dedicated teachers been rewarded? They have given up furlough days and forgone raises for years, he said, in a wealthy state that inexplicably ranks near the bottom in per-pupil funding. He said he feels “demoralized by the expectations placed on us.”

Unkeless told me he doesn’t mind being evaluated in part on how well his students test, but he doesn’t think the tests are smart enough to be very useful. If the national goal is better teachers, he’s all for it, but he’d rather be evaluated by master teachers.

He learns a lot about teaching, he said, from conversations with other instructors, but it’s frustrating that he never gets a chance to watch them work. Instead, he feels as though he’s being told how and what to teach by people who seldom set foot in a classroom.

In the middle of my visit with Unkeless, the parents of one of his students came in for a conference. After they left, Unkeless told me it was gratifying to see parents concerned about a bright kid who got a C in his class, and asking how they could be more helpful.

“She’s a good kid,” Unkeless said, and his eyes brightened as he considered the potential of that one child and all the others.

The great thing about the job, he said, is the opportunity to help them find their voices and find their way. Unkeless speaks of teaching as if it is a privilege. But having watched him in action, I’d say his students have a pretty good deal too.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.