Searching for redemption, a former gang member struggles to outrun his past

In an open blue coffin draped in a sheer veil, Carl Betts was greeted by friends and family.

Hundreds of mourners, dressed in the blue of the 83rd Street Gangster Crips, had gathered at Bethel AME Church on a cloudy morning last year. Some took photos of themselves, repping gang signs, alongside the casket.

Betts, 51, was not a gang member. He had grown up among them but never joined. But it was a distinction lost on those who mourned him, as well as on the young gunman who had fired several rounds into his face.

Among those paying their respects was Melvin Earl Farmer, a former member of the 83rd Street gang, who waited in line for an hour to see his old friend.

“He didn’t look that bad for someone who had his brains shot out,” Farmer said later, outside the church. “It’s good that people will remember him with his face all together.”

Bryan Perry, another former 83rd Street Crip, nodded in agreement. When a car passed by slowly, Perry turned his head to follow the vehicle through the light until it disappeared.

“No one is safe out here,” Perry said. “These young guys out here, just running up and shooting people. It’s just wild.”

Two months later, Perry, 45, was fatally shot outside a convenience store. Police said the shooting was gang-related.

::

In South Central Los Angeles, the narrative is often one of violence. Roles — good guy, bad guy — are defined narrowly.

But there are a handful of people like Melvin Farmer, who exist in a kind of gray area: He maintains bonds with gang members but also with those determined to stamp out the gangs.

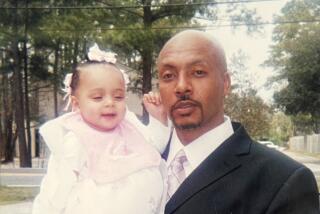

Melvin Farmer was an OG Crip member. After serving year of prison time he has tried to turn his life around and work as a gang interventionist, but he can’t seem to shake his past.

Farmer is known on the streets as an original member of the Crips. It is an association that remains a source of deep pride for him, even at 59. But he craves redemption too — to be the person known for bringing peace to the neighborhood — and he is struggling to redefine his identity and legacy.

According to Farmer, it’s not easy to play the role of peacemaker when the parents of the young men dying in gang wars today “know my history.” The path to glory in the gang world, Farmer says, usually dead-ends in life in prison or death: “You either get tried by 12 or carried by six. That’s how this game goes.”

::

For the past two decades, Farmer has used his gang connections to help end the violence in South L.A. In 1998, he worked with other activists on a program to provide jobs for anyone who turned in a gun, The Times reported at the time. The initiative came after a gang feud had led to weeks of police raids.

Two years later, Farmer spoke to black inmates after several racially charged riots in a county detention center, and he carried their request for segregated prison populations to the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department.

Farmer also worked with black community activists in 2007 to counter a gang-prevention plan proposed by then-Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger, who wanted gang parolees to wear ankle monitors similar to those worn by sex offenders.

In a letter to the governor, Farmer and other activists said the plan did not address the roots of gang violence, such as poverty, unemployment and poor education.

“Melvin does the work that very few people want to do in South Central,” said Najee Ali, a community organizer who has worked with Farmer. “He has used his street credibility to bring peace, while risking his life in doing so.”

Recently, Farmer volunteered to work with City Councilman Marqueece Harris-Dawson’s office to strengthen anti-gang efforts in his South L.A. district. He helped the councilman’s office recruit young men from the area to participate in a community event, Harris-Dawson’s spokesperson said, and met with the deputy chief of staff to discuss ways to combat gang violence.

But Farmer’s works haven’t brought the more permanent role he seeks as a leader in gang-intervention efforts. “We will always have a scarlet letter against us because of our past, no matter how sincerely we work,” Ali said.

Farmer hoped those efforts would lead to something bigger — a paid position as an anti-gang advisor perhaps — that would allow him to use his gang ties to, in effect, go straight. Many of his friends have made that transition. Farmer desired recognition too.

“Ain’t just anybody can walk up and talk to these gangs, but people sometimes don’t see the value in that,” he said. “Especially not from me.”

::

Farmer has been in and out of jail for most of his life. In 1994, he was convicted of drug possession and, under the three strikes law, sentenced to life in prison. But he caught a break. His case was overturned on appeal for an improper search, and when he walked free in 1997, he vowed to change his life.

“Melvin has always been a bit of a knucklehead,” said Ben “Taco” Owens, a gang-intervention worker in South L.A. “He’s done a lot of good since he got out, but he has found himself back into trouble once or twice.”

In the past two decades, Farmer was found guilty on seven counts of driving with a suspended license, two counts of shoplifting and one count each of theft and larceny.

Then, in 2011, he was sentenced to four years in prison for using a stolen credit card in Georgia and almost hitting three police officers with a vehicle as he tried to escape.

Although Farmer served his sentences, society sets up former inmates for failure, noted USC law professor Jody Armour, who studies race and criminal justice. Their criminal records block them from necessary resources such as housing and job opportunities. Coupled with high recidivism rates and poor skills, they cannot secure a stable future. Criminality provides an avenue to make ends meet.

“We put these people in a Catch-22,” Armour said. “They are socially marooned, but there are no real ways to fully return to society. There’s no way to be whole again.”

They are socially marooned, but there are no real ways to fully return to society. There’s no way to be whole again.

— USC law professor Jody Armour

::

Farmer had his first run-in with the law at 13 — a schoolyard bet to steal shoes. His mother couldn’t understand it: She had just bought him shoes the week before. He avoided punishment in juvenile court, but the theft earned him respect. And he wanted more.

A series of violent crimes, including armed robbery, followed. While his peers took their high school yearbook photos, Farmer was posing for mugshots.

Being in a gang was like “being a rock star,” Farmer said. “It made us feel special, invincible, wanted.”

It also was an escape from an abusive father who beat his mother. After Farmer drew a gun on his father and threatened to kill him, his mother recalled, her son was different.

Irene Burke watched her son become consumed by the gang. She sat through his court hearings and sentencing, hoping the punishment would persuade him to leave it all behind and pursue his passion: basketball.

In his teens, Farmer played for Crenshaw High School and cleaned up at neighborhood pickup games. Burke recalled sitting on the sidelines during her son’s games.

“We would be out there screaming, and my daughters would holler, ‘That’s my brother,’ ” Burke said. “And I know I’m his mom, but he was something else, flying up and down the court.”

But he never stayed out of trouble long enough to finish the season. And each time Farmer got out of prison, he would go back to the gang.

Now 75, Burke lives far from South L.A., but she continues to help support her son, regularly sending him money from her Social Security check. She also keeps a $50,000 life insurance policy on him — something she’s done for half a century. Burke dreaded the idea of burying her son, but at least she would be prepared if she had to.

“I don’t know if he is worried about his safety though,” his mother said.

::

About two weeks after burying Betts, Farmer called a meeting between the 83rd Street Gangsters and Hoover Crips at Algin Sutton Recreation Center, a park near the 110 Freeway claimed by the Hoovers.

Since the funeral, police had not found Betts’ killer, several more people had been killed and rumors created tension between the local gangs. Normally, a shot-caller or “big homie” would be responsible for handling any long-standing beef. Farmer instead intervened.

As Farmer pulled up to the park, a group of men blocked the entrance — but then a path was cleared for him as the men showed deference to an original 83rd Street Crip member.

Farmer strolled through the new generation of gang members, walking gingerly on a bad knee. Formerly known as “Skull,” Farmer’s skinny arms swayed in his short-sleeve shirt as he exchanged daps, fist-bumping the young men.

“All these boys have my DNA in their blood,” Farmer said. “I was doing this long before they were born, and so they need to respect me.”

Farmer stepped away and left the two gangs to mingle. Many of the young men had grown up together but had been separated by gang lines. Perhaps they were less likely to kill each other if they reconnected, Farmer thought.

Whether he held any influence with the young men wasn’t clear. One, who identified himself by his street name “Tiny Hawk,” said he didn’t know Farmer well and, in any case, the elder man wasn’t really in a position to tell any of them what to do. “Things are hot out here in the neighborhood, and people ain’t trying to listen to nobody,” he said.

The get-together at the park ended without incident, but the shootings continued. So Farmer staged a few more gatherings, hoping to build on the initial meeting, and there were no killings for weeks. Then someone else was gunned down on July 8; several more were fatally shot the following week.

Gang relations are complicated. Bringing two rival gangs together, he knew, could make both targets for other gangs. But Farmer was proud of what he’d done. He felt a sense of purpose.

::

A month after burying Carl Betts, Farmer went to another funeral — for another former gang member who, like him, had been trying to go straight.

Ladell Rowles, known as “the street apostle,” had set up a nonprofit organization that hosted after-school programs and charity events. In early July 2015, he was shot at point-blank range with a rifle, killed while trying to mediate a dispute among gang members. Police arrested a man in Rowles’ killing but released him because of insufficient evidence.

The congregation of mourners, again dressed mostly in blue, packed New Temple Missionary Baptist Church. A group of men stood vigil on the street outside.

“It was a beautiful service,” Farmer said afterward. “I wonder what they’ll say about me when I die. You can only hope that it will be good.”

Follow me on Twitter @jeromercampbell

ALSO

El Monte police fatally shoot suspected drunk driver after he attempts to run over officers

Storm brings record rainfall to L.A., while snow temporarily closes the Grapevine

Residents in ‘limbo’ as regulators delay cleaning any lead-tainted homes near Exide battery plant

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.