How do you teach English to Americans?

Jesus Perez, 13, an 8th grader from Mountain View Middle School in Moreno Valley, is an English-language learner. He’s pictured here visiting the UCLA campus.

Jose Perez never really worried about why his children had to repeat English-language classes year after year. After all, they were born in California.

Perez assumed the reason for the added instruction was that he and his wife have a rule that everyone speak Spanish at home.

Then, as his son Jesus prepared to enter Mountain View Middle School in Moreno Valley, Perez attended a meeting.

An administrator explained that his son, like about 1 in 5 students at the school, was designated an “English-language learner.” And, like more than 8 out of 10 of those students, he had been in the program since he started school and was at risk of failing to become “proficient” — which often leads to dropping out.

But there was also good news. Jesus was among a group of higher-achieving students selected for a trial program to see if a new approach can help students break through the all-too-common impasse.

If you sat down and had a conversation with them you’d say they are totally fluent in English.

— Patricia Gándara, UCLA education professor

Their teachers would receive extra training and the students would be paired with high school students to help ease the big step from middle school. Parents would need to sign a contract agreeing that they would attend workshops and that they and their children would take part in a research study.

About half of California students are children of immigrants. In contrast with past generations, nearly all of them are born in the U.S., and yet the vast majority end up in English-learner programs for at least part of their education.

In Moreno Valley, the federal government has invested nearly $2 million to find answers to one of the most confounding problems facing educators: How to teach English to students who are born in the United States but fail to fully master some of the language’s complexities.

Jesus Perez, 13, center, an 8th grader from Mountain View Middle School in Moreno Valley, tosses a coin in a fountain for good luck as he and his classmates visit UCLA.

Proficiency can be a tricky label when applied to long-term English learners, says Patricia Gándara, a professor of education at UCLA.

“If you sat down and had a conversation with them you’d say they are totally fluent in English,” she says.

Yet hundreds of thousands of these students in California can’t fully understand Edgar Allan Poe or identify correct verb tenses.

In 2011, the California League of Middle Schools selected Moreno Valley, which had at the time the lowest graduation rates in Riverside County, for a five-year test of its English Learner Families for College proposal. It used 300 students and their parents in 10 local schools.

The three-year goal in the grant proposal was to move about a third of the students out of English-language learner status. This month an external evaluator found that more than two-thirds of the students had reached that goal.

One likely reason Jesus fell behind, his teachers say, is the same reason many students fall behind: He can be shy. Most quiet students who fall behind can compensate in other ways. But stalling in English can prevent a student from doing well in reading, science and other subjects.

When Jesus Perez learned that he would be part of the new program he felt “both happy and kind of bummed.”

He was excited that it might help him, but doubted he’d ever find English instruction captivating.

As the teacher lectured the class, he said, he would often passively take notes and “just kind of stare out into space.”

Right away he learned that was no longer an option. His teacher had received training in something called English 3D. Part of this approach uses almost formulaic classroom routines in which two students grapple with grammar or vocabulary as partners and then in front of the class.

“For a lot of teachers it’s a really big shift,” said Theresa Hancock, who trained the teachers. “There is constantly student interaction.”

Jesus found that he was paying more attention as he read about issues — such as whether children should be allowed to vote — and then shared his ideas for responses within a designated sentence structure with other students.

His teacher, Sherri Blue, also noticed a shift. The quiet student was constantly raising his hand, eager to contribute.

Jesus Perez, 13, center in blue shorts, an 8th grader from Mountain View Middle School in Moreno Valley, joins his classmates visiting UCLA.

After the students visited a college, the first time for almost all of them including Jesus, he decided he wanted to go to UC Riverside or UC Irvine and considered what he needed to do to reach that goal.

In class one morning, elevating his voice over a cacophony of eighth-grade students shouting out their career dreams — “anesthesiologist, firefighter, Marine” — Jesus explained in flawless English why he wanted to be an architect.

“I love math,” he said, sitting rigidly at his desk, “and being an architect involves a lot of degrees and angles.”

Jesus is not the only one in his family motivated by the new teaching approach.

On a March evening after a long day stocking inventory at Target, his father kissed his wife hello and goodbye as she prepared for her night shift at Del Taco.

Then Jose Perez drove Jesus and his older sister to their middle school, where he joined a handful of men and twice as many women, among them a homemaker, a medical assistant and cook.

Perez immigrated to the United States in 1989 from Morelos, Mexico. He had ended his own schooling when he was about his son’s age. His parents were illiterate “and didn’t touch school.”

He and his wife did their best to support their children, but they figured that once they get to school, “it’s up to the teacher and ‘God bless.’”

The trial program, however, hinges on the view that students will succeed only if their parents not only support them but learn to advocate for their education. The Los Angeles-based organization Families in Schools trained the teachers to lead a series of bilingual workshops on how parents — even if they do not speak English, or know how to read — can do that.

Angelena Tavares, who instructed that night’s class, has been teaching in Moreno Valley for 18 years. She bubbled with enthusiasm as she led the parents through exercises. But she said she has noticed a discouraging shift in students’ attitudes.

Most of her English-learner students are now born in the United States, and they do not seem as motivated as in the past.

“The ones who were immigrants would push themselves,” she said.

Children of immigrants project a sense of entitlement, she said. “They are Americanized.”

With both parents working, she says, they are also sometimes lost.

Research supports Tavares’ observations.

“There are a number of studies that show that the immigrant kids are often more ambitious academically” than children born in the U.S. of immigrant parents, UCLA’s Gándara says.

But when the parents are involved in the classes, Tavares says, the students often change their attitudes. “Those kids are like, ‘My parents are into it, and I’m into it.’”

Those kids are like, ‘My parents are into it, and I’m into it.’

— Angelena Tavares, Mountain View Middle School English-learner teacher, on parental involvement in learning

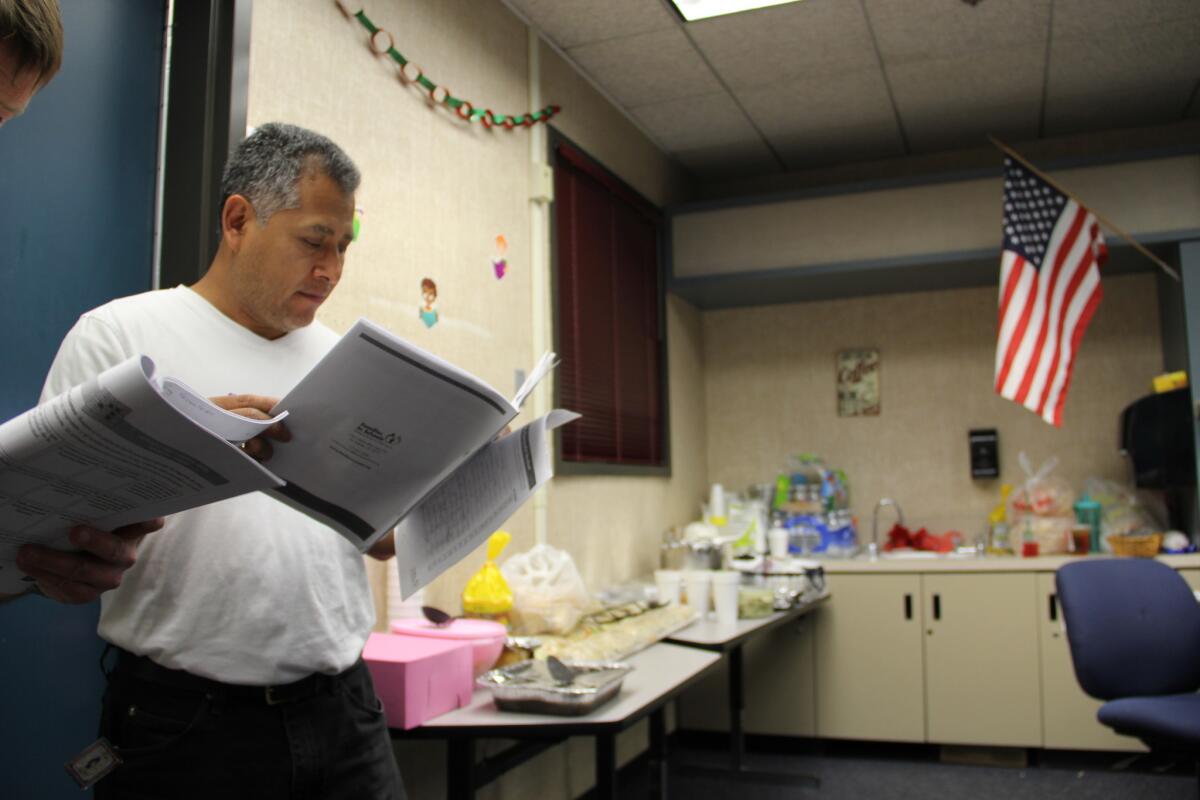

The Los Angeles-based organization Families in Schools trained Moreno Valley teachers to lead a series of bilingual workshops on how parents — even if they do not speak English, or know how to read — can help their students learn English. Jose Perez attends a workshop at Mountain View Middle School.

At the middle school that evening, Jose Perez played “college prep bingo” with the other parents as Jesus chatted in the cafeteria with classmates.

Over a dinner of 3-foot burritos, the eighth-graders held up their cellphones to display texts they had exchanged with student mentors at the high school — a third element of the program.

Jesus has fired off many questions to the student who’s helping him:

“What do you regret most doing in high school?”

“What classes should I take over the summer?”

His most pressing question, however, was whether he would finally pass the English-learner test this summer. His mentor couldn’t answer that one.

But he thinks he is ready, and so do his teachers.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.